The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business (22 page)

Read The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business Online

Authors: Charles Duhigg

Tags: #Psychology, #Organizational Behavior, #General, #Self-Help, #Social Psychology, #Personal Growth, #Business & Economics

One day, a regular customer at Hollywood Video who’d gotten to know Travis a little bit suggested he think about working at Starbucks. “We’re opening a new store on Fort Washington, and I’m

going to be an assistant manager,” the man said. “You should apply.” A month later, Travis was a barista on the morning shift.

That was six years ago. Today, at twenty-five, Travis is the manager of two Starbucks where he oversees forty employees and is responsible for revenues exceeding $2 million per year. His salary is $44,000 and he has a 401(k) and no debt. He’s never late to work. He does not get upset on the job. When one of his employees started crying after a customer screamed at her, Travis took her aside.

“Your apron is a shield,” he told her. “Nothing anyone says will ever hurt you. You will always be as strong as you want to be.”

He picked up that lecture in one of his Starbucks training courses, an education program that began on his first day and continues throughout an employee’s career. The program is sufficiently structured that he can earn college credits by completing the modules. The training has, Travis says, changed his life. Starbucks has taught him how to live, how to focus, how to get to work on time, and how to master his emotions. Most crucially, it has taught him willpower.

“Starbucks is the most important thing that has ever happened to me,” he told me. “I owe everything to this company.”

For Travis and thousands of others, Starbucks—like a handful of other companies—has succeeded in teaching the kind of life skills that schools, families, and communities have failed to provide. With more than 137,000 current employees and more than one million alumni, Starbucks is now, in a sense, one of the nation’s largest educators. All of those employees, in their first year alone, spent at least fifty hours in Starbucks classrooms, and dozens more at home with Starbucks’ workbooks and talking to the Starbucks mentors assigned to them.

At the core of that education is an intense focus on an all-important habit: willpower. Dozens of studies show that

willpower is the single most important keystone habit for individual success.

5.1

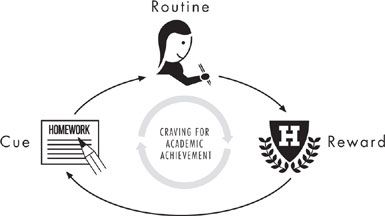

In a 2005 study, for instance, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania analyzed 164 eighth-grade students, measuring their IQs and other factors, including how much willpower the students demonstrated, as measured by tests of their self-discipline.

Students who exerted high levels of willpower were more likely to earn higher grades in their classes and gain admission into more selective schools. They had fewer absences and spent less time watching television and more hours on homework. “Highly self-disciplined adolescents outperformed their more impulsive peers on every academic-performance variable,” the researchers wrote. “Self-discipline predicted academic performance more robustly than did IQ. Self-discipline also predicted which students would improve their grades over the course of the school year, whereas IQ did not.…

Self-discipline has a bigger effect on academic performance than does intellectual talent.”

5.2

And the best way to strengthen willpower and give students a leg up, studies indicate, is to make it into a habit. “Sometimes it looks like people with great self-control aren’t working hard—but that’s because they’ve made it automatic,” Angela Duckworth, one of the University of Pennsylvania researchers told me. “Their willpower occurs without them having to think about it.”

For Starbucks, willpower is more than an academic curiosity. When the company began plotting its massive growth strategy in the late 1990s, executives recognized that success required cultivating an environment that justified paying four dollars for a fancy cup of coffee. The company needed to train its employees to deliver a bit of joy alongside lattes and scones. So early on, Starbucks started researching how they could teach employees to regulate their emotions and marshal their self-discipline to deliver a burst of pep with

every serving. Unless baristas are trained to put aside their personal problems, the emotions of some employees will inevitably spill into how they treat customers. However, if a worker knows how to remain focused and disciplined, even at the end of an eight-hour shift, they’ll deliver the higher class of fast food service that Starbucks customers expect.

The company spent millions of dollars developing curriculums to train employees on self-discipline.

Executives wrote workbooks that, in effect, serve as guides to how to make willpower a habit in workers’ lives.

5.3

Those curriculums are, in part, why Starbucks has grown from a sleepy Seattle company into a behemoth with more than seventeen thousand stores and revenues of more than $10 billion a year.

So how does Starbucks do it? How do they take people like Travis—the son of drug addicts and a high school dropout who couldn’t muster enough self-control to hold down a job at McDonald’s—and teach him to oversee dozens of employees and tens of thousands of dollars in revenue each month? What, precisely, did Travis learn?

Everyone who walked into the room where the experiment was being conducted at Case Western Reserve University agreed on one thing: The cookies smelled delicious. They had just come out of the oven and were piled in a bowl, oozing with chocolate chips. On the table next to the cookies was a bowl of radishes. All day long, hungry students walked in, sat in front of the two foods, and submitted, unknowingly, to a test of their willpower that would upend our understanding of how self-discipline works.

At the time, there was relatively little academic scrutiny into willpower. Psychologists considered such subjects to be aspects of

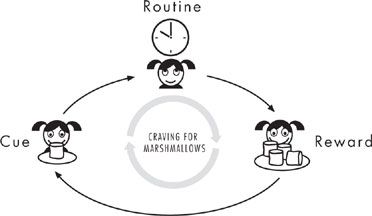

something they called “self-regulation,” but it wasn’t a field that inspired great curiosity. There was one famous experiment, conducted in the 1960s, in which scientists at Stanford had tested the willpower of a group of four-year-olds. The kids were brought into a room and presented with a selection of treats, including marshmallows. They were offered a deal: They could eat one marshmallow right away, or, if they waited a few minutes, they could have two marshmallows. Then the researcher left the room. Some kids gave in to temptation and ate the marshmallow as soon as the adult left. About 30 percent managed to ignore their urges, and doubled their treats when the researcher came back fifteen minutes later. Scientists, who were watching everything from behind a two-way mirror, kept careful track of which kids had enough self-control to earn the second marshmallow.

Years later, they tracked down many of the study’s participants. By now, they were in high school. The researchers asked about their grades and SAT scores, ability to maintain friendships, and their capacity to “cope with important problems.” They discovered that the four-year-olds who could delay gratification the longest ended up with the best grades and with SAT scores 210 points higher, on average, than everyone else. They were more popular and did fewer drugs. If you knew how to avoid the temptation of a marshmallow as a preschooler, it seemed, you also knew how to get yourself to class on time and finish your homework once you got older, as well as how to make friends and resist peer pressure.

It was as if the marshmallow-ignoring kids had self-regulatory skills that gave them an advantage throughout their lives.

5.4

Scientists began conducting related experiments, trying to figure out how to help kids increase their self-regulatory skills. They learned that teaching them simple tricks—such as distracting themselves by drawing a picture, or imagining a frame around the marshmallow, so it seemed more like a photo and less like a real

temptation—helped them learn self-control. By the 1980s, a theory emerged that became generally accepted: Willpower is a learnable skill, something that can be taught the same way kids learn to do math and say “thank you.” But funding for these inquiries was scarce. The topic of willpower wasn’t in vogue. Many of the Stanford scientists moved on to other areas of research.

WHEN KIDS LEARN HABITS FOR DELAYING THEIR CRAVINGS

…

THOSE HABITS SPILL OVER TO OTHER PARTS OF LIFE

However, when a group of psychology PhD candidates at Case Western—including one named Mark Muraven—discovered those studies in the mid-nineties, they started asking questions the previous

research didn’t seem to answer. To Muraven, this model of willpower-as-skill wasn’t a satisfying explanation. A skill, after all, is something that remains constant from day to day. If you have the skill to make an omelet on Wednesday, you’ll still know how to make it on Friday.

In Muraven’s experience, though, it felt like he forgot how to exert willpower all the time. Some evenings he would come home from work and have no problem going for a jog. Other days, he couldn’t do anything besides lie on the couch and watch television. It was as if his brain—or, at least, that part of his brain responsible for making him exercise—had forgotten how to summon the willpower to push him out the door. Some days, he ate healthily. Other days, when he was tired, he raided the vending machines and stuffed himself with candy and chips.

If willpower is a skill, Muraven wondered, then why doesn’t it remain constant from day to day? He suspected there was more to willpower than the earlier experiments had revealed. But how do you test that in a laboratory?

Muraven’s solution was the lab containing one bowl of freshly baked cookies and one bowl of radishes. The room was essentially a closet with a two-way mirror, outfitted with a table, a wooden chair, a hand bell, and a toaster oven. Sixty-seven undergraduates were recruited and told to skip a meal. One by one, the undergrads sat in front of the two bowls.

“The point of this experiment is to test taste perceptions,” a researcher told each student, which was untrue. The point was to force students—but only

some

students—to exert their willpower. To that end, half the undergraduates were instructed to eat the cookies and ignore the radishes; the other half were told to eat the radishes and ignore the cookies. Muraven’s theory was that ignoring cookies

is hard—it takes willpower. Ignoring radishes, on the other hand, hardly requires any effort at all.