The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business (24 page)

Read The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business Online

Authors: Charles Duhigg

Tags: #Psychology, #Organizational Behavior, #General, #Self-Help, #Social Psychology, #Personal Growth, #Business & Economics

The psychologist wanted to understand why. She examined the booklets, and discovered that most of the blank pages had been filled in with specific, detailed plans about the most mundane aspects of recovery. One patient, for example, had written, “I will walk to the bus stop tomorrow to meet my wife from work,” and then noted what time he would leave, the route he would walk, what he would

wear, which coat he would bring if it was raining, and what pills he would take if the pain became too much. Another patient, in a similar study, wrote a series of very specific schedules regarding the exercises he would do each time he went to the bathroom. A third wrote a minute-by-minute itinerary for walking around the block.

As the psychologist scrutinized the booklets, she saw that many of the plans had something in common: They focused on how patients would handle a specific moment of anticipated pain. The man who exercised on the way to the bathroom, for instance, knew that each time he stood up from the couch, the ache was excruciating. So he wrote out a plan for dealing with it: Automatically take the first step, right away, so he wouldn’t be tempted to sit down again. The patient who met his wife at the bus stop dreaded the afternoons, because that stroll was the longest and most painful each day. So he detailed every obstacle he might confront, and came up with a solution ahead of time.

Put another way, the patients’ plans were built around inflection points when they knew their pain—and thus the temptation to quit—would be strongest. The patients were telling themselves how they were going to make it over the hump.

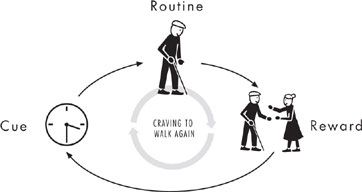

Each of them, intuitively, employed the same rules that Claude Hopkins had used to sell Pepsodent. They identified simple cues

and obvious rewards. The man who met his wife at the bus stop, for instance, identified an easy cue—

It’s 3:30, she’s on her way home!

—and he clearly defined his reward—

Honey, I’m here!

When the temptation to give up halfway through the walk appeared, the patient could ignore it because he had crafted self-discipline into a habit.

PATIENTS DESIGNED WILLPOWER HABITS TO HELP THEM OVERCOME PAINFUL INFLECTION POINTS

There’s no reason why the other patients—the ones who didn’t write out recovery plans—couldn’t have behaved the same way. All the patients had been exposed to the same admonitions and warnings at the hospital. They all knew exercise was essential for their recovery. They all spent weeks in rehab.

But the patients who didn’t write out any plans were at a significant disadvantage, because they never thought ahead about how to deal with painful inflection points. They never deliberately designed willpower habits. Even if they intended to walk around the block, their resolve abandoned them when they confronted the agony of the first few steps.

When Starbucks’s attempts at boosting workers’ willpower through gym memberships and diet workshops faltered, executives decided they needed to take a new approach. They started by looking more closely at what was actually happening inside their stores. They saw that, like the Scottish patients, their workers were failing when they ran up against inflection points. What they needed were institutional habits that made it easier to muster their self-discipline.

Executives determined that, in some ways, they had been thinking about willpower all wrong. Employees with willpower lapses, it turned out, had no difficulty doing their jobs most of the time. On the average day, a willpower-challenged worker was no different from anyone else. But sometimes, particularly when faced with unexpected stresses or uncertainties, those employees would snap and their self-control would evaporate. A customer might begin yelling,

for instance, and a normally calm employee would lose her composure.

An impatient crowd might overwhelm a barista, and suddenly he was on the edge of tears.

5.17

What employees really needed

were clear instructions about how to deal with inflection points—something similar to the Scottish patients’ booklets: a routine for employees to follow when their willpower muscles went limp.

5.18

So the company developed new training materials that spelled out routines for employees to use when they hit rough patches. The manuals taught workers how to respond to specific cues, such as a screaming customer or a long line at a cash register. Managers drilled employees, role-playing with them until the responses became automatic.

The company identified specific rewards—a grateful customer, praise from a manager—that employees could look to as evidence of a job well done.

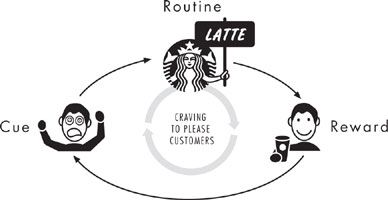

Starbucks taught their employees how to handle moments of adversity by giving them willpower habit loops.

When Travis started at Starbucks, for instance, his manager introduced him to the habits right away. “One of the hardest things about this job is dealing with an angry customer,” Travis’s manager told him. “When someone comes up and starts yelling at you because they got the wrong drink, what’s your first reaction?”

“I don’t know,” Travis said. “I guess I feel kind of scared. Or angry.”

“That’s natural,” his manager said. “But our job is to provide the best customer service, even when the pressure’s on.” The manager flipped open the Starbucks manual, and showed Travis a page that was largely blank. At the top, it read, “When a customer is unhappy, my plan is to … ”

“This workbook is for you to imagine unpleasant situations, and write out a plan for responding,” the manager said. “One of the systems we use is called the

LATTE

method. We

Listen

to the customer,

Acknowledge

their complaint,

Take action

by solving the problem,

Thank

them, and then

Explain

why the problem occurred.

5.19

THE LATTE HABIT LOOP

“Why don’t you take a few minutes, and write out a plan for dealing with an angry customer. Use the

LATTE

method. Then we can role-play a little bit.”

Starbucks has dozens of routines that employees are taught to use during stressful inflection points. There’s the

What What Why

system of giving criticism and the

Connect, Discover, and Respond

system for taking orders when things become hectic. There are learned habits to help baristas tell the difference between patrons who just want their coffee (“A hurried customer speaks with a sense of urgency and may seem impatient or look at their watch”) and those who need a bit more coddling (“A regular customer knows other baristas by name and normally orders the same beverage each day”). Throughout the training manuals are dozens of blank pages where employees can write out plans that anticipate how they will surmount inflection points.

Then they practice those plans, again and again, until they become automatic.

5.20

This is how willpower becomes a habit: by choosing a certain behavior ahead of time, and then following that routine when an inflection point arrives. When the Scottish patients filled out their booklets, or Travis studied the

LATTE

method, they decided ahead of time how to react to a cue—a painful muscle or an angry customer. When the cue arrived, the routine occurred.

Starbucks isn’t the only company to use such training methods.

For instance, at Deloitte Consulting, the largest tax and financial services company in the world, employees are trained in a curriculum named “Moments That Matter,” which focuses on dealing with inflection points such as when a client complains about fees, when a colleague is fired, or when a Deloitte consultant has made a mistake. For each of those moments, there are preprogrammed routines—

Get Curious, Say What No One Else Will, Apply the 5/5/5 Rule—

that guide employees in how they should respond. At the Container Store, employees receive more than 185 hours of training in their first year alone. They are taught to recognize inflection points such as an angry coworker or an overwhelmed customer, and habits, such as routines for calming shoppers or defusing a confrontation. When a customer comes in who seems overwhelmed, for example, an employee immediately asks them to visualize the space in their home they are hoping to organize, and describe how they’ll feel when everything is in its place. “We’ve had customers come up to us and say,

‘This is better than a visit to my shrink,’ ” the company’s CEO told a reporter.

5.21

Howard

Schultz, the man who built Starbucks into a colossus, isn’t so different from Travis in some ways.

5.22

He grew up in a public housing project in Brooklyn, sharing a two-bedroom apartment with his parents and two siblings. When he was seven years old, Schultz’s father broke his ankle and lost his job driving a diaper truck. That was all it took to throw the family into crisis. His father, after his ankle healed, began cycling through a series of lower-paying jobs. “My dad never found his way,” Schultz told me. “I saw his self-esteem get battered. I felt like there was so much more he could have accomplished.”

Schultz’s school was a wild, overcrowded place with asphalt playgrounds and kids playing football, basketball, softball, punch ball,

slap ball, and any other game they could devise. If your team lost, it could take an hour to get another turn. So Schultz made sure his team always won, no matter the cost. He would come home with bloody scrapes on his elbows and knees, which his mother would gently rinse with a wet cloth. “You don’t quit,” she told him.

His competitiveness earned him a college football scholarship (he broke his jaw and never played a game), a communications degree, and eventually a job as a Xerox salesman in New York City. He’d wake up every morning, go to a new midtown office building, take the elevator to the top floor, and go door-to-door, politely inquiring if anyone was interested in toner or copy machines. Then he’d ride the elevator down one floor and start all over again.

By the early 1980s, Schultz was working for a plastics manufacturer when he noticed that a little-known retailer in Seattle was ordering an inordinate number of coffee drip cones. Schultz flew out and fell in love with the company. Two years later, when he heard that Starbucks, then just six stores, was for sale, he asked everyone he knew for money and bought it.

That was 1987. Within three years, there were eighty-four stores; within six years, more than a thousand. Today, there are seventeen thousand stores in more than fifty countries.

Why did Schultz turn out so different from all the other kids on that playground? Some of his old classmates are today cops and firemen in Brooklyn. Others are in prison. Schultz is worth more than $1 billion. He’s been heralded as one of the greatest CEOs of the twentieth century. Where did he find the determination—the willpower—to climb from a housing project to a private jet?

“I don’t really know,” he told me. “My mom always said, ‘You’re going to be the first person to go to college, you’re going to be a professional, you’re going to make us all proud.’ She would ask these little questions, ‘How are you going to study tonight? What are you going to do tomorrow? How do you know you’re ready for your test?’ It trained me to set goals.