The Psychopath Inside (16 page)

Read The Psychopath Inside Online

Authors: James Fallon

Oddly, seeing a neurologically impaired child in pain really gets to me. I played myself as a mad scientist in the Russian movie

Dau

, about the Nobel Prizeâwinning physicist Lev Landau, and

during the filming I started to tear up when they rolled in a cage full of crying babies. When I saw two who had neurological disorders (fetal alcohol syndrome, Down syndrome), I almost unraveled. This reaction to children with developmental disorders goes back to my youth. A sister of a friend of mine had Down syndrome and that stuck with me. When I was delivering drugs for my father's and uncle's pharmacy, I would run into more children with developmental disorders and they seemed to be distressed. So I think this is one case where I had strong empathy early in life, and it stayed in my emotional response repertoire while other emotions faded. It may have become a conditioned response triggering sadness, because I don't have that for any other people.

My involvement with charity and good works is predominantly with complete strangers, or just acquaintances of people I know. Diane and I give a lot personally and anonymously to charity. I think it's our duty. And I do a lot of work for charities as an adviser and a lot of service work on committees, and I refuse to take money for it. To me it's part of my role as a state-paid professor. I will do this at the same time I am leaving my best friends and family members in the lurch. I have excuses for this behavior, but even I don't buy them.

The fact that I give to charity may seem to go against my disagreement with welfare. But welfare allocates resources from people who have earned them toward a long-term system that does nothing to encourage its dependents to leave it, so in the long term it's a complete failure. Meanwhile, I'm not so callous as to ignore the fact that there are many destitute people starving on

the street, and certain well-managed charities are great at helping them get on their feet. In Africa, I saw need, so I spent money on housing and medical and educational supplies. But I had to do it secretively so I didn't attract opportunistic parasites.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

I have become more aware of my lack of empathy in recent years, but sometimes my subconscious does the work for me. These moments come out of nowhere, most often and most vividly in dreams. The dream this one particular night in 2008 woke me up and left me in a daze because the feeling associated with it was so intense, and because it seemed to arise from a part of my brain that was silent when I was awake.

Here is the four a.m. note I wrote to myself about the dream:

I was on a journey and found myself in the Irish countryside. I came upon a large garden party at a comely mansion and decided to enter through the back gates and as I roamed through the party I came into a cavernous main party room, a sort of dark wood-lined beer hall. Someone asked me what I was looking for and I said, half jokingly, “the truth.” . . . I offered that my sense of love and truth and beauty had been a somewhat opaque mishmash until my wife had developed lymphoma. I then became infused into the imagery from where I spoke. As I continued, Diane and I went through this transformation, and we became embedded in this illuminated plasma, on our backs. This very comfortable and sweetly illuminated plasma was actually the layers of a watercolor and

pastel painting within which I was embedded. And as I lay on my back, within the painting itself, the colors of the painting started to dissolve and washed around me in pure and mixed spectral hues, spinning and washing off, layer by layer, in this most beautiful kaleidoscope of swirling, wonderful colors. And then the last layers of colors finally washed off this huge painting I was part of and I was left, lying on my back on the plain white canvas. And I asked myself, “Where is all the truth and beauty and love?” and what this was all about. And I turned my head to the right, and there was my wife Diane, lying next to me. And in and through this moment of epiphany, I saw true love and was completely happy. The guru and his friends at the table all raised their hands and yelled, “He found the answer,” and then the trinity of wizards all floated off.

The dream happened in the middle of a year or two of particularly bad behavior on my part, and it probably got to me. At that moment, I knew exactly how I felt about Diane and how my lack of empathy can inadvertently damage such a gift as her.

And yet the dream didn't stop me. The devastating series of flirtations mentioned earlier happened soon after.

A Party in My Brain

I

n 2010, the Norwegian Consulate invited me to give a talk on depression at a small two-day meeting. I had spoken about the subject several times before and had taken special interest in how psychiatric disordersâincluding depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophreniaâcan affect creativity. Here I planned to talk about the usefulness of combining imaging and genetics and psychological testing into mathematical models to understand psychiatric diseases like depression, and I would build up my case by first talking about personality disorders. I figured this would be an excellent venue to test out my Three-Legged Stool hypothesis about psychopathic murderers and psychopaths in general in front of some world-class psychiatrists known for being both learned and circumspectâa potentially tough crowd. I was confident about the hypothesis scientifically and also happy the theory got me off the hook, since I didn't really believe I was a psychopath.

The Oslo symposium was titled “Mental Illness: Bipolar Disorder and Depression.” The symposium was interesting for several reasons. In Norway, as in much of Scandinavia, people are

hesitant to admit to, or discuss, the fact that they or others in their circle of family and friends have a mental disorder, particularly depression. Ellen Sue Ewald, director of education and research at the Norwegian Honorary Consulate General in Minneapolis, and Reidun Torp, a noted Alzheimer's disease expert at the University of Oslo, took on this national problem by organizing this meeting, and invited one of the top clinical experts on depression in the world, Hossein Fatemi of the University of Minnesota, to discuss the medical and psychiatric issues surrounding the different types of major depression and bipolar disorder. Ewald also managed to convince former prime minister Kjell Magne Bondevik to talk about his own struggles with bipolar disorder, which first afflicted him during his first term. In 1998, Bondevik had demonstrated considerable bravery and leadership in publicly admitting his condition, and had taken a leave of absence to start therapy. Against the odds, he'd then gone on to serve a second term and enjoy an overall successful tenure. This had been a breakthrough.

The night before our talks, Dr. Fatemi and I met to try to coordinate our lectures. Fueled by the hypomanic energy I always get before a talk, plus a couple of vodkas, I ripped through my PowerPoint slides. As I sped through them on the computer, I glanced up at Hossein, who had a curious look on his face. He had recognized the hypomania, my pressure of speech while I was talking to him, and based on this amped-up kineticism he suspected something I had never even considered before. Hossein

explained that I might have bipolar disorder. That conference would be the first time I seriously considered the chance that I may actually have a mood disorder. I had heard ten years prior from a close friend and colleague of mine, a noted neurologist, that he had only learned of his own bipolar disorder from a fellow neurologist; he had failed to see his own disorder, a common occurrence among neurological and psychiatric clinicians, especially in their early years of practicing medicine.

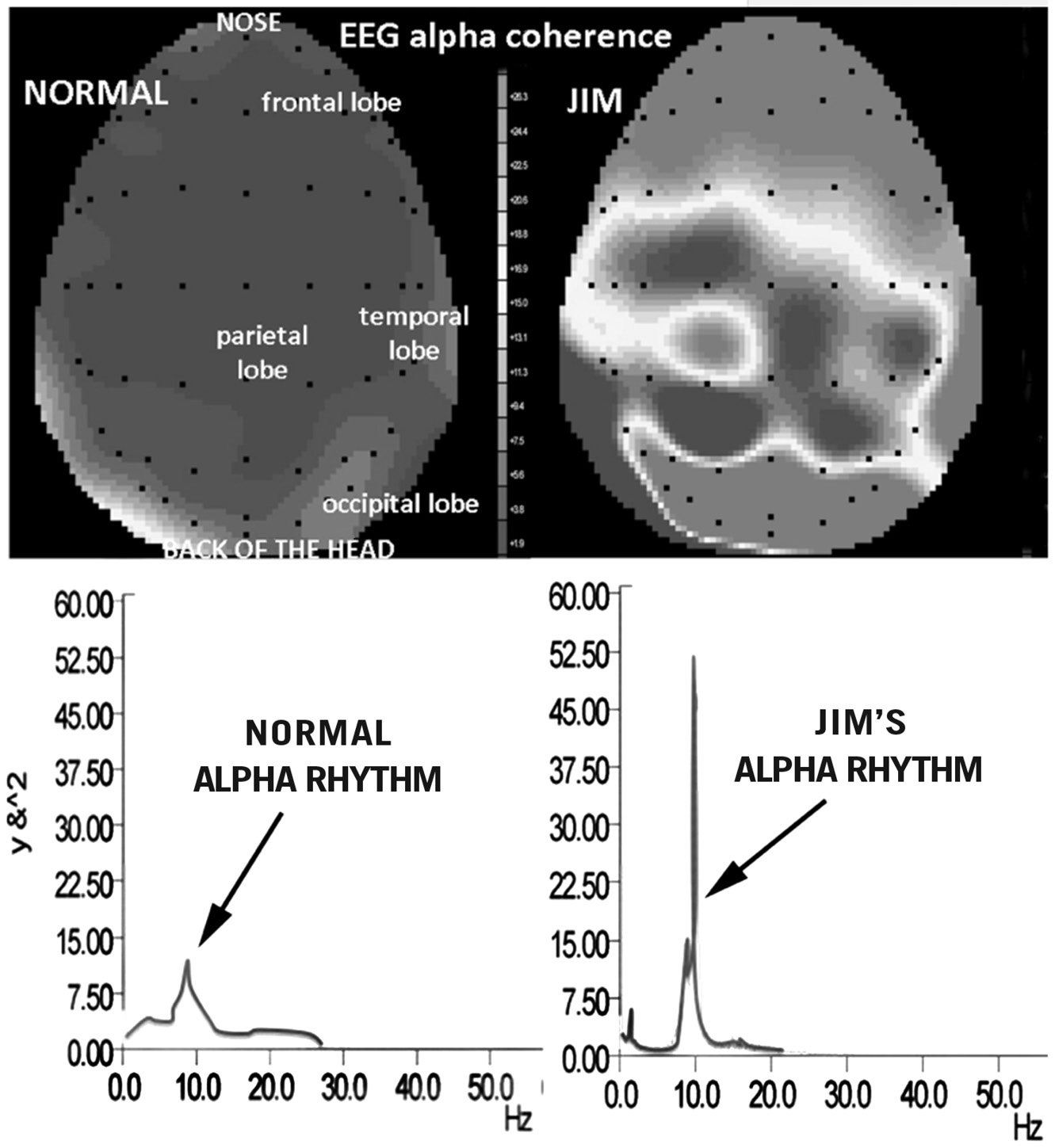

The revelation that I may have had bipolar disorder most of my life without realizing it floored me. A long-term clinical colleague and friend, Adrian, a psychiatrist and neurophysiologist, had remarked in 2005 that I had an unusual EEG pattern that showed a unique alpha rhythm. An alpha rhythm is a synchronized firing of neurons in the range of 8 to 12 Hz, or cycles per second. Mine was a very high-voltage, single-frequency rhythm that reached into my frontal lobe, as shown in figure 8A. At the top are two color maps of the alpha wave “coherence,” with much of a normal person's alpha coherence being present in the occipital lobe, at the back of the head. My alpha coherence, on the other hand, is intense in level and spread over much of my occipital, temporal, and frontal lobes. The actual alpha rhythms of a normal person versus my own are shown in the lower part of the figure. A normal alpha peak tends to be somewhat wide, spread over a frequency range of 9 to 10 Hz, whereas mine is very high in voltage with a narrow spread confined to about 9.7 Hz.

FIGURE 8A:

My EEG alpha coherence.

He'd said that this pattern was consistent with a sort of highly focused, meditative Zen state, but also was indicative of a significant risk for depression, although he didn't have an explanation for that association. Of course, I reveled in the whole Zen brain aspect and blew off the depression part, a typical reaction of denial. Many clinicians who have known me well for decades have

always remarked that I am clearly hypomanic. This is a wonderfully elated state of being, in which one feels like one is being continually pumped with sunshine all the time. I would get into this state for many days or even weeks at a stretch. It is the type of disease no one ever wants to be cured of. It feels wonderful, and those of us with it feel great all the time, though we're probably quite obnoxious to those around us. The idea that this exuberance could be associated with bipolar disorder was theoretically acceptable to me. I already knew that bipolar disorder is defined more by the bouts of mania or hypomania than by the episodes of depression.

Thinking about this kept me up all night, and it ultimately changed the way I view disease. I also reflected on various episodes in my life, looking for signs that I might have missed before. I had never considered myself depressed, though I have experienced numerous episodes of dread, generally associated with some metaphysical and existential crises. They started when I was about nine and are characterized by an overwhelming rush of negative thoughts, followed by utter dread. They last fifteen to thirty minutes, during which I cycle through a series of thoughts about mortality, God, the afterlife, the concept of the soul, and the meaning of existence, and eventually arrive at the conclusion that nothing at all matters and life is not worth living.

They're not fun, but at least these episodes last only a few minutes. (Two of my kids and one of my grandkids also get them; we call them the “death yips.”) Until that day in Oslo, I never considered that these were anything more than my emotional

response to my obsession with death and mortality. It never occurred to me that they might be a symptom of depression.

Most of us assume depression is the result of external tragedies, or of stress or dark thoughts, but often episodes of depression happen spontaneously in the brain and then lead to those dark thoughts. Similar phenomena happen to us all the time. For example, it is likely that nocturnal emissions cause the sleeping ideations we call wet dreams, and not the other way around. Another example is how we think of free will. While we all think that we first plan our actions and that they are then willfully carried out, in some cases a part of our frontal lobe may actually “decide” first, unconsciously, that we will perform an act, and after we carry out the act we fool ourselves into thinking we planned it. In other words, we are fooling ourselves into thinking we are in control of our actions. This is how the need for a comforting, or at least logical, narrative can occasionally drive our conscious existence. Our body and brain work in harmony to decide what to do, and seconds later we may tell ourselves a story that we actually meant to do it.

The day after discussing my slide presentation with Dr. Fatemi, I gave my talk at the University of Oslo to a mix of politicians, media, students, neuroscientists, and psychiatrists. After considering the serotonin and inferior temporal and frontal lobe imbalances in my brain the night before my Oslo talk, I had added some additional slides. In one, I showed an illustration of the brain, identifying an area that can lower mood by reducing dopamine transmission in other areas. This region, called the

subgenual cingulate gyrus, may be chronically “switched on” in people with depression. The neurologist Helen Mayberg of Emory University found that you could immediately treat major depression by turning it off using deep brain stimulation (DBS), a technique that involved threading an electrode deep into the brain. Reduced activity in this area is associated with psychopathy, which may explain why you don't see a lot of major depressives who are also psychopaths.

After some anatomical slides, I presented a slide listing many of my clinical, subclinical, physical, and behavioral phenotypes (my actual traits and disorders). I also listed my risk for related illnesses through an ingenuity “network analysis” that takes into consideration all of my genetic alleles, the interaction of these genes, and what diseases and traits are inferred from this network. I had just received these results, as a more thorough follow-up to the genetic results I'd received two years prior for the

Wall Street Journal

article. It confirmed that I had many of the genes for aggression, but added more detail on genes related to several other conditions.

On the left of the slide were all of the syndromes I've had in my life, and their age of onset and age of offset where appropriate: asthma, allergies, panic attacks, OCD, hyper-religiosity, hypertension, obesity, essential tremor, addictions, hypomania, high-risk behaviors, putting others at risk, impulsivity, insomnia, flat empathy, aggression, hedonism, individualism, creative bursts, and verbosity. Next to that list of traits and clinical conditions, were statistical estimates of how at risk my genes put me for

particular disorders, including various neurological, psychological, behavioral, endocrine, respiratory, and metabolic disorders. The phenotype-genotype pairings matched up very well. (After examining the nightmare combination of genes I inherited, Fabio had said, “It's surprising that you ever made it through fetal development, let alone your adolescence.” I could have been another of my mother's miscarriages, or a case of teenage suicide.) At the end of the question-and-answer period of the talk, in which I never mentioned my own potential depressive episodes, the chairman of psychiatry said that, based on my genetic information and my energetic performance, I appeared to have a subtype of bipolar disorder, thus confirming Hossein's suspicions from the night before.

In the six years of personal discovery I had experienced since my brain scan, this was the first time I was really stunned. I realized I had never had a clue about the deeper groundwaters that had shaped me. Later that evening at a post-symposium, at the home of my dear friend of thirty-five years the polymath neuroscientist Ole Petter Ottersen,

rektor

(president) of the University of Oslo, I talked with other clinicians, and they supported the idea that I had been bipolar all along. One called my rather revealing personal lecture a “Lutheran confession.” For the life of me, I still do not know what that means. But afterward I started to think that my firm denial of God was a product of, rather than a cause of, depression. (Now I'm not so sure about God; maybe there is a God and an afterlife after all, who knows?)

Thanks to great feedback from circumspect neuroscientists

and clinicians, the Oslo trip had firmed up my confidence in my Three-Legged Stool theory. But somehow I had “contracted” bipolar disorder during the trip. Like Wile E. Coyote running off a cliff, I hadn't seen the reality of my own bipolar disorder until I slowed down long enough to recognize the gravity of the situation.

I learned much about the clinical intricacies of depression and bipolar disorder listening to Dr. Fatemi and his lecture during those two days in Oslo, comparing the clinical picture with the neuroanatomical circuits I had drawn up for the talk, and further fleshing out my knowledge of the disorder after I returned home from Norway.

The National Institutes of Health's

A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia

defines bipolar disorder as follows: “Bipolar disorder is a condition in which people go back and forth between periods of a very good or irritable mood and depression. The âmood swings' between mania and depression can be very quick . . . In most people with bipolar disorder, there is no clear cause for the manic or depressive episodes. The manic phase may last from days to months.” Since the age of nineteen, I have displayed 85 percent of the listed symptoms during my hypomania, including little need for sleep, reckless behavior, elevated mood, and hyperactivity. In the depressed phase people usually experience sadness, difficulty concentrating, fatigue, low self-esteem, and hopelessness.

Depression is a complex mix of mood disorders that, taken together, affect 10 to 15 percent of the global population at some point in their lives, making it one of the most common psychiatric maladies. Becoming depressed as a result of a loss of a spouse,

child, friend, or career is, of course, normal. But depression may occur in the absence of any clear environmental stimulus, and in many cases runs in families, suggesting it is, at least in part, genetic. The key feature differentiating bipolar disorder, formerly called manic-depression, from major depressive disorder (MDD), also known as major or clinical depression, is the presence of hypomania or mania that cycles with the down or depressed moods. There are other types of depression such as seasonal affective disorder (SAD), typically found in people with a brain rhythm dysfunction that acts up during the dark winter months; postpartum depression (PPD); dysthymia (a mild, long-lasting form of depression); and melancholic depression, in which the person is unable to experience pleasure, a condition referred to as anhedonia. There are some severe forms of major depression, including catatonia, in which the person hardly ever moves, and psychotic major depression (PMD), in which the person experiences not only depression but also hallucinations and delusions.