The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry (2 page)

Read The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry Online

Authors: Jon Ronson

Tags: #Social Scientists & Psychologists, #Psychopathology, #Sociology, #Psychology, #Popular Culture.; Bisacsh, #Social Science, #Popular Culture, #Psychopaths, #General, #Mental Illness, #Biography & Autobiography, #Social Psychology, #History.; Bisacsh, #History

They threw up their hands in defeat. If this was a puzzle that academics couldn’t solve, maybe they should bring in someone more brutish, like a private investigator or a journalist. Deborah asked around. Which reporter might be tenacious and intrigued enough to engage with the mystery?

They went through a few names.

And then Deborah’s friend James said, “What about Jon Ronson?”

On the day I received Deborah’s e-mail inviting me to the Costa Coffee I was in the midst of quite a bad anxiety attack. I had been interviewing a man named Dave McKay. He was the charismatic leader of a small Australian religious group called The Jesus Christians and had recently suggested to his members that they each donate their spare kidney to a stranger. Dave and I had got on pretty well at first—he’d seemed engagingly eccentric and I was consequently gathering good material for my story, enjoyably nutty quotes from him, etc.—but when I proposed that group pressure, emanating from Dave, was perhaps the reason why some of his more vulnerable members might be choosing to give up a kidney, he exploded. He sent me a message saying that to teach me a lesson he was putting the brakes on an imminent kidney donation. He would let the recipient die and her death would be on my conscience.

I was horrified for the recipient and also quite pleased that Dave had sent me such a mad message that would be good for my story. I told a journalist that Dave seemed quite psychopathic (I didn’t know a thing about psychopaths but I assumed that that was the sort of thing they might do). The journalist printed the quote. A few days later Dave e-mailed me: “I consider it defamatory to state that I am a psychopath. I have sought legal advice. I have been told that I have a strong case against you. Your malice toward me does not allow you to defame me.”

This was what I was massively panicking about on the day Deborah’s e-mail to me arrived in my in-box.

“What was I

thinking

?” I said to my wife, Elaine. “I was just enjoying being interviewed. I was just enjoying talking. And now it’s all fucked. Dave McKay is going to sue me.”

thinking

?” I said to my wife, Elaine. “I was just enjoying being interviewed. I was just enjoying talking. And now it’s all fucked. Dave McKay is going to sue me.”

“What’s happening?” yelled my son Joel, entering the room. “Why is everyone shouting?”

“I made a silly mistake. I called a man a psychopath, and now he’s angry,” I explained.

“What’s he going to do to us?” said Joel.

There was a short silence.

“Nothing,” I said.

“But if he’s not going to do anything to us, why are you worried?” said Joel.

“I’m just worried that I’ve made him angry,” I said. “I don’t like to make people upset or angry. That’s why I’m sad.”

“You’re lying,” said Joel, narrowing his eyes. “I

know

you don’t mind making people angry or upset. What is it that you aren’t telling me?”

know

you don’t mind making people angry or upset. What is it that you aren’t telling me?”

“I’ve told you everything,” I said.

“Is he going to attack us?” said Joel.

“No!” I said. “No, no! That definitely won’t happen!”

“Are we in danger?” yelled Joel.

“He’s not going to attack us,” I yelled. “He’s just going to sue us. He just wants to take away my money.”

“Oh God,” said Joel.

I sent Dave an e-mail apologizing for calling him psychopathic.

“Thank you, Jon,” he replied right away. “My respect for you has risen considerably. Hopefully if we should ever meet again we can do so as something a little closer to what might be called friends.”

“And so,” I thought, “there was me once again worrying about nothing.”

I checked my unread e-mails and found the one from Deborah Talmi. She said she and many other academics around the world had received a mysterious package in the mail. She’d heard from a friend who had read my books that I was the sort of journalist who might enjoy odd whodunits. She ended with, “I hope I’ve conveyed to you the sense of weirdness that I feel about the whole thing, and how alluring this story is. It’s like an adventure story, or an alternative reality game, and we’re all pawns in it. By sending it to researchers, they have invoked the researcher in me, but I’ve failed to find the answer. I hope very much that you’ll take it up.”

Now, in the Costa Coffee, she glanced over at the book, which I was turning over in my hands.

“In essence,” she said, “someone is trying to capture specific academics’ attention to something in a very mysterious way and I’m curious to know why. I think it’s too much of an elaborate campaign for it to be just a private individual. The book is trying to tell us something. But I don’t know what. I would love to know who sent it to me, and why, but I have no investigative talents.”

“Well . . .” I said.

I fell silent and gravely examined the book. I sipped my coffee. “I’ll give it a try,” I said.

I told Deborah and James that I’d like to begin my investigation by looking around their workplaces. I said I was keen to see the pigeonhole where Deborah had first discovered the package. They covertly shared a glance to say, “That’s an odd place to start but who dares to second-guess the ways of the great detectives?”

Their glance may not, actually, have said that. It might instead have said, “Jon’s investigation could not benefit in any serious way from a tour of our offices and it’s slightly strange that he wants to do it. Let’s hope we haven’t picked the wrong journalist. Let’s hope he isn’t some kind of a weirdo, or has a private agenda for wanting to see inside our buildings.”

If their glance did say that, they were correct: I did have a private agenda for wanting to see inside their buildings.

James’s department was a crushingly unattractive concrete slab just off Russell Square, the University College London school of psychology. Fading photographs on the corridor walls from the 1960s and 1970s showed children strapped to frightening-looking machines, wires dangling from their heads. They smiled at the camera in uncomprehending excitement as if they were at the beach.

A stab had clearly once been made at de-uglifying these public spaces by painting a corridor a jaunty yellow. This was because, it turned out, babies come here to have their brains tested and someone thought the yellow might calm them. But I couldn’t see how. Such was the oppressive ugliness of this building it would have been like sticking a red nose on a cadaver and calling it Ronald McDonald.

I glanced into offices. In each a neurologist or psychologist was hunkered down over their desk, concentrating hard on something brain-related. In one room, I learned, the field of interest was a man from Wales who could recognize all his sheep as individuals but couldn’t recognize human faces, not even his wife, not even himself in the mirror. The condition is called prosopagnosia— face blindness. Sufferers are apparently forever inadvertently insulting their workmates and neighbors and husbands and wives by not smiling back at them when they pass them on the street, and so on. People can’t help taking offense even if they consciously know the rudeness is the fault of the disorder and not just haughtiness. Bad feelings can spread.

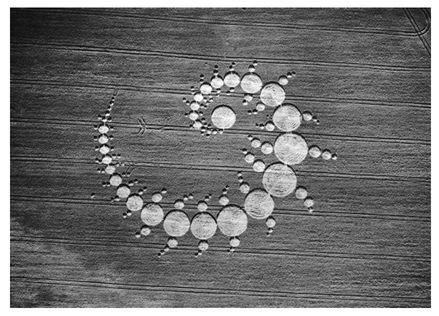

In another office a neurologist was studying the July 1996 case of a doctor, a former RAF pilot, who flew over a field in broad daylight, turned around, flew back over it fifteen minutes later, and there, suddenly, was a vast crop circle. It was as if it had just

materialized

.

materialized

.

The Julia Set.

It covered ten acres and consisted of 151 separate circles. The circle, dubbed the Julia Set, became the most celebrated in crop circle history. T-shirts and posters were printed. Conventions were organized. The movement had been dying off—it had become increasingly obvious that crop circles were built not by extraterrestrials but by conceptual artists in the dead of night using planks of wood and string—but this one had appeared from nowhere in the fifteen-minute gap between the pilot’s two journeys over the field.

The neurologist in this room was trying to work out why the pilot’s brain had failed to spot the circle the first time around. It had been there all along, having been built the previous night by a group of conceptual artists known as Team Satan using planks of wood and string.

In a third office I saw a woman with a

Little Miss Brainy

book on her shelf. She seemed cheerful and breezy and good-looking.

Little Miss Brainy

book on her shelf. She seemed cheerful and breezy and good-looking.

“Who’s that?” I asked James.

“Essi Viding,” he said.

“What does she study?” I asked.

“Psychopaths,” said James.

I peered in at Essi. She spotted us, smiled and waved.

“That must be dangerous,” I said.

“I heard a story about her once,” said James. “She was interviewing a psychopath. She showed him a picture of a frightened face and asked him to identify the emotion. He said he didn’t know what the emotion was but it was the face people pulled just before he killed them.”

I continued down the corridor. Then I stopped and glanced back at Essi Viding. I’d never really thought much about psychopaths before that moment, and I wondered if I should try to meet some. It seemed extraordinary that there were people out there whose neurological condition, according to James’s story, made them so terrifying, like a wholly malevolent space creature from a sci-fi movie. I vaguely remembered hearing psychologists say there was a preponderance of psychopaths at the top—in the corporate and political worlds—a clinical absence of empathy being a benefit in those environments. Could that really be true? Essi waved at me again. And I decided, no, it would be a mistake to start meddling in the world of psychopaths, an especially big mistake for someone like me, who suffers from a massive surfeit of anxiety. I waved back and continued down the corridor.

Deborah’s building, the University College London Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, was just around the corner on Queen Square. It was more modern and equipped with Faraday cages and fMRI scanners operated by geeky-looking technicians wearing comic-book T-shirts. Their nerdy demeanors made the machines seem less intimidating.

“Our goal,” said the center’s website, “is to understand how thought and perception arise from brain activity, and how such processes break down in neurological and psychiatric disease.”

We reached Deborah’s pigeonhole. I scrutinized it.

“Okay,” I said. “Right.”

I stood nodding for a moment. Deborah nodded back. We looked at each other.

Now was surely the time to reveal to her my secret agenda for wanting to get inside their buildings. It was that my anxiety levels had gone through the roof those past months. It wasn’t normal. Normal people definitely didn’t feel this panicky. Normal people definitely didn’t feel like they were being electrocuted from the inside by an unborn child armed with a miniature Taser, that they were being prodded by a wire emitting the kind of electrical charge that stops cattle from going into the next field. And so my plan all day, ever since the Costa Coffee, had been to steer the conversation to the subject of my overanxious brain and maybe Deborah would offer to put me in an fMRI scanner or something. But she’d seemed so delighted that I’d agreed to solve the

Being or Nothingness

mystery I hadn’t so far had the heart to mention my flaw, lest it spoil the mystique.

Being or Nothingness

mystery I hadn’t so far had the heart to mention my flaw, lest it spoil the mystique.

Now was my last chance. Deborah saw me staring at her, poised to say something important.

“Yes?” she said.

There was a short silence. I looked at her.

“I’ll let you know how I get on,” I said.

The six a.m. discount Ryanair flight to Gothenburg was cramped and claustrophobic. I tried to reach down into my trouser pocket to retrieve my notepad so I could write a to-do list, but my leg was impossibly wedged underneath the tray table that was piled high with the remainder of my snack-pack breakfast. I needed to plan for Gothenburg. I really could have done with my notepad. My memory isn’t what it used to be. Quite frequently these days, in fact, I set off from my home with an excited, purposeful expression and after a while I slow my pace to a stop and just stand there looking puzzled. In moments like that everything becomes dreamlike and muddled. My memory will probably go altogether one day, just like my father’s is, and there will be no books to write then. I really need to accumulate a nest egg.

Other books

The Wannabes by Coons, Tammy

Dog Training The American Male by L. A. Knight

Flight of the Vajra by Serdar Yegulalp

Isle of Palms by Dorothea Benton Frank

Dark World (Book I in the Dark World Trilogy) by Q. Lee, Danielle

Magical Influence Book One by Odette C. Bell

Dying For You by Evans, Geraldine

Your Chariot Awaits by Lorena McCourtney

A Million Steps by Kurt Koontz