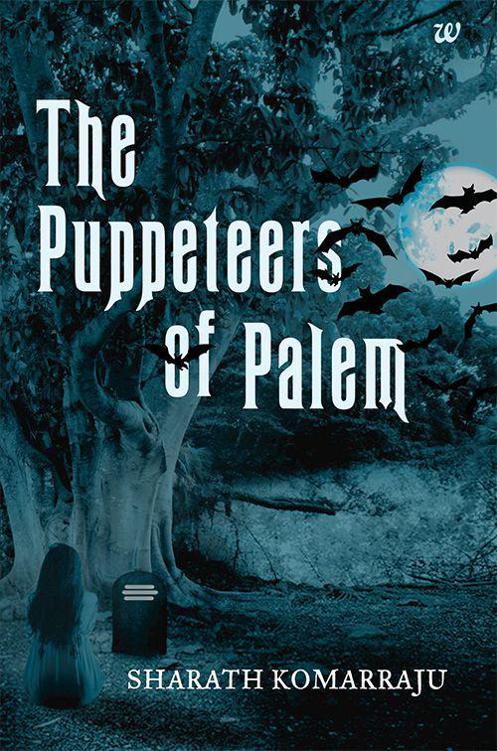

THE PUPPETEERS OF PALEM

Read THE PUPPETEERS OF PALEM Online

Authors: Sharath Komarraju

Also by Sharath Komarraju

Murder in Amaravati (2012)

Banquet on the Dead (2012)

The Winds of Hastinapur (2013)

Tell him what you think of his books on his personal blog:

sharathkomarraju.com

Facebook:

WriterSharath

Twitter:

AuthorSharathK

westland ltd

61, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600 095

93, 1st Floor, Sham Lal Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002

First published by westland ltd 2014

First ebook edition: 2014

Copyright © Sharath Komarraju

2014

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-93-84030-68-1

Typeset: PrePSol Enterprises Pvt. Ltd.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously and any resemblance to any actual person

living or dead, events and locales is entirely coincidental.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, circulated, and no reproduction in any form, in whole or in part (except for brief

quotations

in critical articles or reviews) may be made without written permission of the publishers.

Aditi, this is for you.

Chapter One

1984

A

vadhani leaned over the edge of the cot, away from the children, and spat out on the mud floor a pasty, orange mix of Manikchand gutkha and Crane betel nut. Then he turned back and smiled at his audience, making no attempt to conceal his decaying teeth. There was no need to, they had all seen his teeth numerous times before.

‘So Chotu,’ he said, and pulled one of the young children onto his lap. ‘Have you ever heard the story of Rama and Sita?’

A collective groan went up. The child on his lap looked up at him and pinched his nose. The seventy-watt Philips bulb, flickering on its last legs, covered the porch in a dim, smudgy light. Even if Avadhani had been a young forty-something, he would not have been able to see the children’s faces. At his present age, he could forget about it.

He removed his glasses and squinted at them. A moth, one of the three that had been circling the light, fell on one of the lenses and started to hurry away. He closed his thumb and index finger around it. Then he squeezed. He felt its wings flutter under his fingers for a second before going limp. After he had satisfied himself that it was dead, he raised his thumb and swatted it away.

To his right, he heard the son of Anjaneyulu kill a mosquito on his thigh with one decisive slap. He murmured in approval.

There had been no mosquitoes here in Palem where Avadhani had grown up. No mosquitoes, and no moths. It was all thanks to this industrialization going on in Dhavaleshwaram

—

all these factories and men and machines and god knew what else. They did not even have light bulbs back then. They did not need any.

‘You have told us that story

so

many times, Thatha,’ Chotu said. Chotu was the son of

—

now, whose son was Chotu? Well, whoever he was, he sat on Avadhani’s lap and played with the smudge left by the moth on his glasses. ‘That, and the story of those five men and their hundred brothers.’

‘Yes Thatha,’ someone else from the group piped up. ‘Too many times.’

‘Yes, yes, too many times.’

‘Something new.’

‘Yes, a new one.’

Avadhani felt a prick under his left arm. He resisted the instinct to move and instead waited a second, allowing the pain to build up. Yes, let the mosquito think it was safe. He would wait for just the

right

moment and

—

slap! He examined his hand. Nothing. He had missed. Damn! These mosquitoes used to be slow and lazy when he was young. Now, with all this industrialization and factories and machines…

‘Orey, who are you? Son of Mangamma, aren’t you?’

The boy did not speak. Chotu looked up at him and nodded.

‘Why are you pulling Venkataramana’s hair?’

‘He pulled my hair first, Thatha.’

‘I did not see that.’

‘He did it when you were not looking!’

Avadhani sighed and looked away. The radio crackled to life and hissed out an old Shree Shree song. It tended to do that nowadays, his radio. It stopped and started whenever it wished, much like that Ambassador his son had bought last year. Avadhani had told him that a bicycle was a much better investment. A bicycle ran for as long as you pedalled. It needed no petrol. It did not have an attitude. It did not stop and moan or belt out random songs at you.

‘Give that thing a whack for me, will you, Chanti?’ he said.

The children sat there in silence. They were all there

—

yes, the son and daughter of the carpenter Subbai were here too

.

Subbai, whose father had once made this very cot for

his

father. They made things to last back then, in the old days. His cot did not creak once in all these years. Subbai had been a mere chit of a boy then, about as old as his son and daughter were now.

All those years ago, on nights like these, Subbai used to come to Avadhani’s house. He always used to sit next to that girl

—

Venkatamma’s daughter

—

what was her name? Yes, Gowri. The bulb on his porch had only been a twenty-watt one in those days, but even in that light, Avadhani had seen how they smiled at each other.

They always stopped coming once they reached a certain age. Subbai and Gowri stopped too. But they did not stop seeing each other. They did not stop smiling at each other. When they had got married, they had come and touched his feet. ‘I will send my children to you every night, Avadhanayya,’ he had said. ‘Tell them the stories you told me.’

And he had. Gowramma’s kids…Subbai’s kids were here. But what were their names? He had been very good at remembering names in his youth. But now, all he remembered were their parents’ names. He remembered perfectly well whose kids they each were, but their names… Well, he

was

getting a little long in the tooth…

‘Did you not see,’ he said to the son of Mangamma, ‘what little hair Venkataramana’s father has? Who will marry Venkataramana if you pull out all his hair, boy?’

Venkataramana patted his hair and huffed. ‘Why, Thatha, all my uncles have

this much

hair. My mother says I got

their

hair.’

Avadhani ran a palm across his bald patch and smiled. The light whirred each time it flickered. Another moth took the dead one’s place. Directly under the bulb, his old radio sat in brooding silence. The two big speakers on either side of the cassette holder resembled the eyes of a drunk. Avadhani peered into one of them, half expecting the box to reach out and whisper something confidentially into his ear.

That song… yes, the song that had played on it before Chanti had thwacked it… it had been so long…

‘Thatha,’ Chotu said. ‘I am feeling sleepy.’

That was Chotu’s way of saying, ‘Tell me a story now.’

Avadhani looked up at the sky, at the dark, squiggly spots of the full moon. There had been a full moon that night too. That song and that night… oh, how well he remembered. His memory was not as bad as he thought. But then, this was not something a man forgot as long as he lived. This was one of those things that you took with you to your pyre.

He leaned away, spat again and licked his lips clean. Facing the children, he said, ‘Do you want to hear a new story?’

‘Yes! Yes, yes!’

He lay on his side and propped himself up on his elbow. With his free hand he picked off bits of betel leaves stuck between his teeth and chewed on them. Chotu was now sitting on the floor with the rest of the group.

‘Have you heard the story of Lachi?’ he said at last. Even now, he could not say that name without a catch in his throat. Lachi would now have been old enough to be a mother. She was as old as Subbai, was she not? Yes, if that was true, she would have had kids as old as

these.

Her body would have withered. Her beauty would have waned.

But to him, she had always remained the thirteen-year-old that skipped along the streets of Palem in that green silk langa

and red jacket, laughing in that clear, ringing voice. In his mind’s eye, she always wore her hair in two plaits. And in his mind’s eye, she always looked at him with love in her eyes. In reality, she had done only the first two. Not the third.

Never

the third.

The silence at his question was but expected. People in Palem were not supposed to speak of Lachi. On the rare occasions that they did, they took great care not to say her name. She was always ‘the witch’ or ‘the wretch’, or simply, ‘that woman’.

‘Her name is Vijayalakshmi,’ Avadhani said, adopting his storytelling voice. ‘Their hut used to be where Poola Rangayya’s shack is now. Her father used to milk the buffaloes in Saraswatamma’s house.’

Images floated into his head, unannounced. He remembered how he used to stand behind the stage and watch her drink water from the school well. He had volunteered to teach Sanskrit at the school just so he could see her. To this day, he could not decide whether Lachi had looked more becoming in her langa

and red jacket or in her blue school skirt and white buttoned shirt.

One of the children, Seeta

—

Mallamma’s daughter, by the colour of her skin and the twist in her lip

—

said slowly, ‘You are telling uf afout fichi

Lachi?’ A muffled giggle made its way around the group, as it usually did when this girl spoke.

Avadhani nodded. ‘Did you know that Lachi was once not pichi? Do you want to know what it was that drove her mad?’

The child looked up at the light doubtfully and back at Avadhani. Then she nodded.

Avadhani cleared his throat. ‘Vijayalakshmi went to Dhavaleshwaram for her school studies. When she completed her matriculation, she came back here and married.’ There was another catch in his throat. He himself had gone to Hyderabad for his Intermediate years. He and Lachi, he had thought back then, would be the most educated people in Palem. He had planned to talk to her father once she returned. After all, he had thought, what fear could he possibly have?

But Lachi had gone to town for studies, and had learnt some of the ways of a town girl. She had learnt to love.

‘Fhe killed her huffand, didn’t fhe?’ Seeta asked Avadhani. Her upper lip curved upward and pointed at her cheek, resting in an impossible angle, as though it had been stitched into place. Two of her front teeth were always visible underneath. She sat in such a position that the light shone upon her grotesque half and shrouded the good half in darkness.

‘Yes, my dear,’ Avadhani said, smiling at her kindly. ‘But she loved her husband.’

‘Fhe killed him with a ftone,’ Seeta said. ‘On the head.’

The other children gasped. Chotu’s little mouth opened in a perfect circle and his eyes blinked up at Avadhani.

Avadhani said, ‘Chakali Sangayya was a drunk. He drank like a fish. And do you know what Vijayalakshmi did when his kidneys failed?’

‘What are kidneys?’

‘They are like hearts, Chotu. But we have two of them. In here.’ Avadhani poked himself in the ribs. ‘Do you know what she did? She gave him one of hers. I am telling you, kids, she loved him.’

‘But if she did

…

’

‘She went to the Shivalayam.’

They did not say anything. The light flickered.

‘Everyone in the village knows that you simply do not go to the Shivalayam at any time, let alone at night. Why Lachi went there that night, nobody knows. What she saw there, that also nobody knows. But that night, after Sangadu came back, drunk as usual, she fed him. And when he went to sleep, she went to the kitchen, picked up her rolling stone, went to the cot on which her husband was sleeping and…’

Avadhani stopped, looked meaningfully at the children, closed his right hand in a fist and pressed it silently into his left palm.

The kids gasped again.

‘Why…why did fhe kill him?’ Seeta asked.

‘She became mad. The next morning when the milkman called at their door, there she was, Sangadu’s head in her lap, the bloody stone by her side, and her hands, soaked in his blood, caressing his hair. She was singing to him.’

Yes, that same song

.

Challani raja o Chandamama

…

‘And when she saw Varadayya at the door, she smiled and nodded at him to come in. She lifted her bloody hand like this,’ and he stretched out his hand toward the children, ‘and beckoned him to come to her.’

The children shrank back. ‘Did Varadayya go?’

‘Oh, he went all right. He dropped his cans and ran from the house, and he ran and ran, stopping only when he got to Saraswatamma’s house. He told them everything and returned to the hut with a few servants.’

Avadhani brought his hand to his nose. As it always did when he thought of Lachi, it smelled of mangoes. He had gone to their shack, one summer afternoon, to get some mangoes. Their hands had touched when she placed the fruits in his hands. That was the only time he had ever touched her. The scent of mangoes… the scent of her touch would never leave him.

‘Then what happened, Thatha

?

’

Avadhani said, ‘When Varadayya came back, they did not find her. People said they had seen her walk in the direction of the Shivalayam. Some say they saw her jump into the old well. Some say she ran away to another village. But all of them agree on one thing. All of them who claim to have seen her that day say that she had been laughing.’

‘And no one has seen her since?’

‘Not for a few years. Then people started seeing her around the shack and around the Shivalayam. She had killed Sangadu on a full moon night, so she came back on full moon nights and roamed the village, rock in hand.’

Chotu looked around, then stood up and hurried over to Avadhani’s lap. The group huddled a little closer and no one said a word.

Then Avadhani said softly, ‘I saw her too.’

The kids rose up in a titter. Avadhani silenced them with a wave of the hand and continued. ‘It was only a year or two ago. I had to go to Dhavaleshwaram and I thought I would take a short cut through Erragadda canal. It was when I got close to the Shivalayam that I started to hear her.’

‘Hear what?’ they asked in chorus. ‘Hear what, Thatha?’

‘It was a very low sound at first, but slowly, as I got closer to the lingam, the jingle of her anklets grew louder. I looked up at the sky. It was a full moon. I had my radio to my ear. Do you know which song was playing?’

The kids nodded slowly.

Avadhani nodded along with them. ‘Yes. Good. And then I saw her, right next to the lingam. She was sitting there with her legs splayed, as if she was washing clothes. She held a smooth rock in her hand, which she rubbed against the base of the lingam again and again. When I approached, she looked up at me and smiled.’

Avadhani paused and looked at their faces. The cot creaked under his weight. The moths flapped their wings against the bulb at jerky, unsteady intervals. The buzz of mosquitoes was constant.

‘And then,’ he said, ‘she raised her hand towards me. She held out the rock and nodded to me, calling me closer.’