The Race to Save the Lord God Bird (9 page)

Read The Race to Save the Lord God Bird Online

Authors: Phillip Hoose

CAMP EPHILUS

When Nature has work to be done, she creates a genius to do it.

âRalph Waldo Emerson

L

ATE INTO THE NIGHT AT KUHN'S CABIN, THE CORNELL RESEARCHERS WENT OVER their options for transporting the sound equipment five miles through the muck to the Ivory-bills' nest. The choices all looked bad. Driving the trucks through the swamp would be impossible. The sound truck alone weighed nearly a ton, and the ground was like soup.

ATE INTO THE NIGHT AT KUHN'S CABIN, THE CORNELL RESEARCHERS WENT OVER their options for transporting the sound equipment five miles through the muck to the Ivory-bills' nest. The choices all looked bad. Driving the trucks through the swamp would be impossible. The sound truck alone weighed nearly a ton, and the ground was like soup.

Finally they hit on an ingenious plan. They would drive the trucks to some dry place in Tallulah and take the sound truck apart, disconnecting the instruments from the truck. Then they would rebuild the recording system in Ike's farm wagon and turn it into the sound truck. Ike's mules could pull it into the swamp. They'd build a camp on some dry spot near the Ivory-bills' nest, and from there they could spend as much time as they needed to film, record, and study the birds. It just might work.

They drove their trucks into town, and Doc went to ask the mayor for a work site. He gave them a choice location. A few minutes later, puzzled prisoners at the town jail peered out through the bars of their cell windows at two heavy black trucks pulling up onto the lawn. Then three well-dressed strangers got out, greeted them pleasantly, and began to jerk wires from the inside of one truck, placing them neatly on the

ground. When word got around about what they were doing, one of the prisoners hollered out, “Hey! I know right where the peckerwoods are if you can get me out of here!”

ground. When word got around about what they were doing, one of the prisoners hollered out, “Hey! I know right where the peckerwoods are if you can get me out of here!”

By the dawn of Monday, April 8, all the instruments were rebuilt in Ike's farm wagon, and the four mules clopped off for the swamp. Having finished his sketches of Ivory-bills, Professor Sutton had departed for Texas to scout out other rare birds, leaving Allen, Kellogg, and Tanner to observe the woodpeckers. It took all day to reach the nest, with Kellogg and Allen riding the two lead mules and Tanner, Kuhn, and Ike's son, Albert, scrambling behind on foot. They finally stopped in front of a giant oak tree about three hundred feet from the Ivory-bills' nest.

The Cornell team transports its sound equipment to Camp Ephilus

The men flung a wide canvas tent, like a circus big top, over the sound truck, and then propped it up with small saplings, lashing the canvas to nearby trees. They stocked up palmetto fans between the roots of a tree and spread their sleeping blankets on top, hoping the pile would be high enough off the ground to keep them dry at

night. Mounting a pair of binoculars on a tripod, they aimed it at the nest hole and scooted a lawn chair behind it so that one of them could sit and watch the nest during daylight. Then they pointed the sound mirror toward the nest hole and built a cooking site. They called their new home “Camp Ephilus,” a pun on the Ivory-bill's genus name,

Campephilus.

night. Mounting a pair of binoculars on a tripod, they aimed it at the nest hole and scooted a lawn chair behind it so that one of them could sit and watch the nest during daylight. Then they pointed the sound mirror toward the nest hole and built a cooking site. They called their new home “Camp Ephilus,” a pun on the Ivory-bill's genus name,

Campephilus.

The next afternoon both Ivory-bills briefly left the nest. Jim Tanner scrambled up an elm that stood just twenty feet from the nest tree and hammered a plank between two limbs. He quickly added to it a small frame over which he draped a scrap of canvas. He backed down the tree again, nailing boards into the trunk as he descended. Now they had a “blind” that would give them a closer look if the birds would accept such near neighbors.

The men settled down to the nuts and bolts of an ornithologist's work. They worked in shifts, never taking their eyes off the nest hole during daylight, recording in their journal even the most ordinary behavior of the birds. As Doc's notes from April 11 show, the Ivory-bills eyed their new neighbors nervously:

[8:45 a.m.] Tanner went up to the blind and pulled up the camera. The female once flew to the nest hole but became alarmed and flew away after climbing to the top of the stub. While Tanner was setting his camera, the male came and entered the nest. [I] frightened the male from the nest by rubbing the tree. In about twenty minutes it returned, climbed to the hole, looked around and looked in, but after about half a minute or more it became alarmed by the rattle of the camera and flew off. Ten or fifteen minutes later it returned and ⦠finally entered the hole.

Doc Allen takes his turn at the spotting scope

Doc, Tanner, and Kellogg knew they were taking a risk. If they scared the birds off, there was no assurance there were any more to be seen. Even worse, the disturbance

could disrupt the birds' breeding season. On the other hand, saving the species from extinction depended on knowing enough about it to make recommendations. This was the best chance anyone would probably ever have. Their expedition had become more than a sound-recording experiment; now they were on a rescue mission as well.

could disrupt the birds' breeding season. On the other hand, saving the species from extinction depended on knowing enough about it to make recommendations. This was the best chance anyone would probably ever have. Their expedition had become more than a sound-recording experiment; now they were on a rescue mission as well.

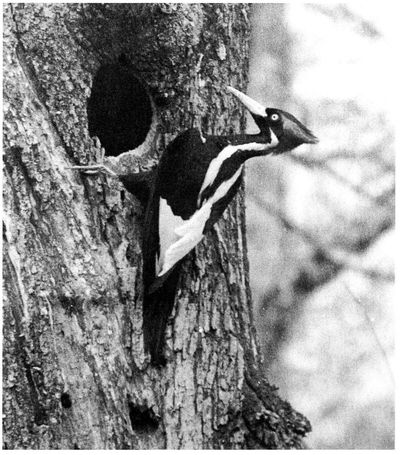

The male Ivory-bill arrives at the nest hole as the female appears at the opening. The Cornell team took this close-up from a blind built in a nearby tree

The Ivory-bills' pattern was the same every day: the male and female took turns incubatingâsitting onâthe eggs inside the nest hole. The male took the night shift, staying with the eggs until about 6:30 a.m. At that hour he rapped on the inside of the hole, delivering an impatient message that echoed through the forest. If his mate was late in arriving, he stuck his head out of the hole and uttered a few “yaps” or “kents,” but he never left his post until she got back. When she did, the two birds seemed to chatter for a while, and then the male remained at the nest for about twenty more minutes, preening his feathers, before zooming off somewhere, probably to find food or to sleep. For the rest of the day, the couple took turns incubating in shifts of about two hours. The female always left at about 4:30 in the afternoon, and stayed away all night.

Another forest creature who slept little and took off at night was Jim Tanner. Now he knew what Doc had meant by describing him as the team's “handy man” who would “act in any necessary capacity.” At Camp Ephilus, Tanner was the cook, the builder, the climber, the porter, and the acrobat who was able to get the camera and the sound mirror closest to the birds. He could soon operate all the equipment. Since there was only room for two to sleep at the camp, every night Tanner sloshed two miles to Ike's home, crawled into bed with Albert, and fell into a brief, deep sleep. He was up at 4:30 each morning and back in camp, hauling water through the darkness and chopping wood to get a fire going and cook for his professors. After scrubbing pots, he took up his morning watch of the Ivory-bills, which usually began at

about 6 a.m. Far from feeling used, he was thrilled. What did sleep matter when you had the chance to study North America's rarest bird close-up? Dirty, sticky, bug-bitten, always a little tired, and still not yet twenty-one, Jim Tanner figured he was one of the luckiest people on earth.

about 6 a.m. Far from feeling used, he was thrilled. What did sleep matter when you had the chance to study North America's rarest bird close-up? Dirty, sticky, bug-bitten, always a little tired, and still not yet twenty-one, Jim Tanner figured he was one of the luckiest people on earth.

THE SPRINT WEST

After five days of observing the birds, the team came to a crossroads. Though they longed to stay with the Ivory-bill family until the eggs hatched and the young were raised, they had other rare birds to record, birds scattered throughout the whole country. Kuhn hiked in with a telegram for Doc, a reminder from a colleague that if they didn't get to western Oklahoma by May 1, they would lose their chance to record another of America's rarest birds, the Lesser Prairie Chicken.

Once again a late-night talk produced a plan. If all went as they hoped, they could dash to Oklahoma, record the prairie chickens, and make it back to Camp Ephilus in two weeks. By then, the young Ivory-bills should have hatched and still be in the nest, not quite ready to fly and still being fed by their parents. J. J. Kuhn volunteered to check in on the nest while they were gone. That seemed the best they could do.

ECOLOGICAL DISASTER

During World War I, prairie farmers plowed under their deep-rooted native grasses and planted shallow-rooted wheat in their place to feed troops overseas.

Prosperity followed until, for some reason, it simply stopped raining. By the time the Cornell team got to Oklahoma, there hadn't been a soaking rainstorm for four years. But the wind blew unceasingly, whipping the unbound, powdery soil into towering clouds of dust that blotted out the sun, covered machinery, and suffocated farm animals. People slept with masks on, tried to keep the dust out of their food, and prayed constantly.

Doc sent for Ike and the mules, the sound truck was reassembled, and the team rumbled westâstraight into the worst dust storm in U.S. history. Sunday, April 14, 1935, began as a day with a piercingly blue sky, but when the wind started blowing, it swept up the soil of Oklahoma and Kansas into a terrifying black wall of dust seven thousand feet high. The dust blew eastward all the way across the country, even dumping prairie soil onto ships in the Atlantic Ocean. Reports of the mighty storm kept the Cornell team stalled for three days in western Louisiana. When they began to drive again, they saw a landscape that seemed as strange as the moon's. With the windshield wiper going all the time, they coughed their way across the prairie.

You can hear the wind's bleak howl in the background of their recordings of the Lesser Prairie Chicken, finally accomplished on the eighth day. With Camp Ephilus and the family of Ivory-bills always on their minds, they drove almost nonstop to Colorado and Kansas, making more recordings, and then raced back to Louisiana. There was no way to telephone Kuhn. They only hoped they weren't too late.

CRAWLING SAWDUST

Little things rule the world.

âHarvard biologist Edward O. Wilson

Â

The team didn't make it back to the Ivory-bill nest until May 9, nearly a month after they had left. They had missed their chance; the birds were gone. Kuhn had visited the nest late in April and found the pair behaving strangely. Each bird spent most of its time nervously poking its head into the nest hole, then entering the nest for just a few minutes, and then flying off to another nearby tree. They preened themselves almost constantly, and after a while they stopped bringing food to the nest altogether. Then they disappeared.

The scientists examined the nest thoroughly, hoping for clues that would tell them why the birds left without rearing young. Inside the hole were tiny fragments of eggshell and a thin, even layer of what looked like sawdust. There was no sign of blood or struggle, no torn feathers or other evidence that a hawk or an owl or a raccoon had slipped into the nest and carried off or eaten the young. They swept the nest contents into a paper bag and took it back to their hotel in Tallulah. The next morning, Doc emptied the contents of the bag onto a desk and turned on a lamp for a closer look. Tanner and Kellogg gathered around. The “sawdust” quickly sprang to life under the hot lightbulb. Soon the desk was seething with tiny mites that stormed up their hands, biting all the way. Yelping, the three men raced for water, scrubbed their arms, and bagged up as many of the tiny creatures as they could. Doc sealed them in an envelope and mailed them off to Cornell so that a mite expert could tell them what species they were.

There turned out to be nine different species. Some ate only wood, fungi, and algae,

but at least three ravenously ate warm-blooded creatures. Allen remembered how nervous the adult Ivory-bills had seemed at the nest, and how much time they had spent preening their feathers. He wondered if the newly hatched birds hadn't been overwhelmed by this army of mites, or if maybe they hadn't even been born at all. Maybe the adults had been so busy trying to pick mites out of their feathers that they hadn't spent enough time incubating the eggs. But then again, the egg fragments probably meant the young had hatched. So what had happened to the chicks?

but at least three ravenously ate warm-blooded creatures. Allen remembered how nervous the adult Ivory-bills had seemed at the nest, and how much time they had spent preening their feathers. He wondered if the newly hatched birds hadn't been overwhelmed by this army of mites, or if maybe they hadn't even been born at all. Maybe the adults had been so busy trying to pick mites out of their feathers that they hadn't spent enough time incubating the eggs. But then again, the egg fragments probably meant the young had hatched. So what had happened to the chicks?

The next day, Allen, Kuhn, Tanner, and a visitor from the National Park Service scouted on horseback for another nest. After seven tough miles they heard faint sounds similar to the calls the parents had made when exchanging shifts at the nest back at Camp Ephilus. Kuhn dismounted and tiptoed closer until he spotted a male's red crest disappearing into a hole nearly fifty feet up in a dead oak hanging over a small clearing. The men tied up their horses and concealed themselves in a thicket of poison ivy and catbrier for two hours, watching the nest and scribbling notes. Around noon they saw the sign they were looking forâthe male flew into the nest with a “big borer grub held lengthwise in his bill”âbaby food. And sure enough, a few minutes later they heard what Doc described as “a weak buzzing from the young ⦠Apparently they were too small to swallow the grub for [the male] left [and flew] with it to a tree one hundred feet away and apparently swallowed it himself.”

At last they had what they wanted: a nest with young birds inside to observe. They hustled back to Tallulah, reassembled Ike's wagon for sound at the jail, and dragged everything back into the swamp, arriving at the new nest before noon on May 14. But once again the forest was still and the Ivory-bills were gone. They waited all afternoon for the birds to return, then gave up and examined the nest. Again there was no sign of blood or struggle. There were no eggs or shells or feathers. This time there weren't even mites. It was as if the parents had cleaned the nest carefully and checked out.

Doc Allen kept trying to fit the clues together into a pattern, but every time there were missing pieces. In some ways the birds' behavior at the two nests was similar to that of birds at a third nest Kuhn told him he had observed two years earlier. These woodpeckers had also seemed to be working hard to incubate eggs and feed young, except that they were extremely nervous and jumpy. Sometimes they changed places

twenty times an hour. They finally deserted the nest before their nestlings could fly or feed themselves. Kuhn had peered into the nest, but it had been empty. He didn't think mites had been there. To Doc, the one link between the three nests was that in each case the adults had managed to hatch their young, but then lost them soon after.

twenty times an hour. They finally deserted the nest before their nestlings could fly or feed themselves. Kuhn had peered into the nest, but it had been empty. He didn't think mites had been there. To Doc, the one link between the three nests was that in each case the adults had managed to hatch their young, but then lost them soon after.

Allen thought about predators. Ivory-bill nests had big holes, big enough for a Great Horned Owl or a large hawk to enter, but there was never a sign of a fight or a killing. What was going on? He began to wonder if something very serious might be happening here. Was the problem genetic? Maybe there were just too few birds left to produce sturdy stock. Maybe all the years of logging and specimen hunting had finally left so few adults so closely related to one another that the offspring they produced could stay alive for only a few days. It was what happened in many species when first cousins mated. Family groups of Ivory-bills had grown increasingly isolated, and interacted only with each other. There were only a very few mates to choose from. Scientists call this “inbreeding.”

Doc Allen hoped there was still time to save the species. He felt that extinction was not only a tragedy but a sign of human defeat, and that he had a moral responsibility not to give up on a fellow creature if it could be saved. But he needed to know more. Just as a doctor needs to understand the behavior of a virus or a bacterium in order to prescribe a cure for an infection, he had to know exactly why these birds were dying in order to save them.

GIVING VOICE TO BIRDS AT LAST

The Cornell sound expeditionariesâmainly Tanner, Allen, and Kelloggâtraveled almost fifteen thousand miles and came home with ten miles of sound film.

They recorded the voices of nearly one hundred of America's rarest birds, including this Golden Eagle, and later transferred them to phonograph records that found their way into thousands of homes.

Besides the only voice recording ever of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, they recorded the honk of the Trumpeter Swanâthen almost as rareâthe gobbling Lesser Prairie Chicken, screaming hawks, and the eerie wail of the Limpkin. The Cornell pioneers gave more feathered creatures a place in the choir and made ours a more tuneful America.

The Cornell crew headed west again to record other birds, and then back to Ithaca loaded down with steel canisters of sound film. The most prized segment of all, the part that got

shown again and again all over the country, lasts only thirty seconds. It begins with a big Hollywood directorâlike voice (Kellogg's) saying, “Ivory-billed Woodpecker; Cornell Catalogueâcut one.” Then the viewer sees Ike's truck being hauled into the Tensas swamp by four mules moving away from the camera, with Tanner and Albert scrambling behind on foot.

shown again and again all over the country, lasts only thirty seconds. It begins with a big Hollywood directorâlike voice (Kellogg's) saying, “Ivory-billed Woodpecker; Cornell Catalogueâcut one.” Then the viewer sees Ike's truck being hauled into the Tensas swamp by four mules moving away from the camera, with Tanner and Albert scrambling behind on foot.

Then the magic part: suddenly there's footage of a male Ivory-billed Woodpecker poking his head into and out of a nest, close-up and alive with frantic energy. He gives off a series of loud, hornlike “yaps” and “kents.” The sounds continue as the camera moves to Doc, sitting in the lawn chair at Camp Ephilus, shirt buttoned up against the bugs, looking through the binoculars at the nest as a campfire crackles in the background. Finally the camera swings to Paul Kellogg twisting dials in the sound truck, and then the screen goes black.

Cornell's historic film captures the Ivory-bill at its nest

Three-quarters of a century later, those brief tooting sounds remain the only recordings ever made of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker's voice, and the film the only record of what the astonishing bird looked like as it moved. The members of the Cornell sound team almost certainly returned from their adventures proud to have made a major contribution to science, and to have documented images and sounds important to American history. But as they settled down to their lectures and classrooms and labs, they must have had trouble keeping their minds from straying to the giant mystery they had left behind at the Singer Refuge.

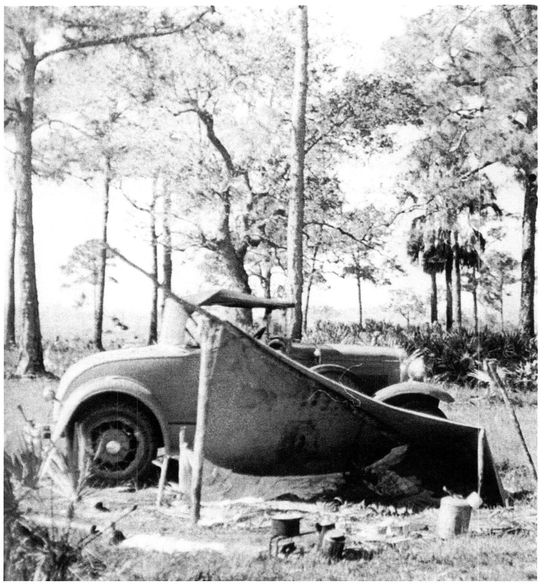

Jim Tanner's 1931 Model A Ford coupe

Other books

La comunicación no verbal by Flora Davis

Reap by James Frey

The Reluctant Guest by Rosalind Brett

The Rebel and His Bride by Bonnie Pega

Doomsday Warrior 07 - American Defiance by Ryder Stacy

Vanquish by Pam Godwin

Heller's Girlfriend by JD Nixon

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

Jane Bonander by Dancing on Snowflakes

B-Movie War by Alan Spencer