The Race to Save the Lord God Bird (7 page)

Read The Race to Save the Lord God Bird Online

Authors: Phillip Hoose

“DOC”

As the Plume War raged, American students studied the bird pictures that came with their Junior Audubon membership kits, and roamed the countryside looking for birds. One of these students, Roger Tory Peterson, got his kit in 1919 when he was an eleven-year-old seventh-grader in Jamestown, New York. It cost a dime, and it seemed like a waste of money until one day, in school, he started painting a picture of a Blue Jay. Something about the colors sparked his imagination.

ROGER TORY PETERSON'S FAMOUS BOOK

By the time he was twenty-six, Roger Tory Peterson (shown here as an older man) had painted pictures of every bird species found in the eastern United States. Then he set out to collect his bird portraits into a single pocket-sized book that could help amateur bird-watchers tell the species apart.

Five publishing companies turned him down before Houghton Mifflin published his work as

A Field Guide to the Birds.

The book sold out in one week. It popularized bird-watching by pointing out simple ways of identifying birds and became one of the most important books of the twentieth century.

A Field Guide to the Birds.

The book sold out in one week. It popularized bird-watching by pointing out simple ways of identifying birds and became one of the most important books of the twentieth century.

THE BRONX COUNTY BIRD CLUB

In

the late 1920s nine intensely competitive boys and young menâincluding Roger Tory Petersonâraced around the five boroughs of New York City, tracking down rare birds and learning together how to identify them. Calling themselves the Bronx County Bird Club (BCBC), they turned bird-watching into a sport. From their clubhouse near the Harlem River, they issued challenges to other teams of birders around New York City to see who could find the most birds in twenty-four hours.

the late 1920s nine intensely competitive boys and young menâincluding Roger Tory Petersonâraced around the five boroughs of New York City, tracking down rare birds and learning together how to identify them. Calling themselves the Bronx County Bird Club (BCBC), they turned bird-watching into a sport. From their clubhouse near the Harlem River, they issued challenges to other teams of birders around New York City to see who could find the most birds in twenty-four hours.

Using maps, binoculars, and coordinated strategies, they prepared for birding contests as if they were going to war. They especially loved to show up older bird-watchers from clubs around New York City. While their elders were stuck at their jobs, the boys got out of school in midafternoon and used the hours to survey the contest area in advance. One of their favorite sites was a dump in the Bronx where they once discovered four Snowy Owls feeding on rats.

The BCBC was rarely beaten.

He was still thinking about this the next Saturday when he and a friend went exploring. They had just crested a hill when Roger spotted a clump of brown feathers clinging to the trunk of an oak tree. The object looked dead, but somehow it was still attached to the tree. Puzzled, Roger walked up to it, extended his finger, and touched it. “It came instantly to life,” he later wrote, “looked at me with wild eyes and dashed away in a flash of golden wings.” It was a Common Flicker, a kind of woodpecker, sleeping with its face tucked into the feathers of its back. That single moment changed Roger Peterson's whole life. “Ever since,” he later wrote, “birds have seemed to me the most vivid expression of life. They have dominated my daily thoughts, my reading and even my dreams.”

Millions of children soaked up information about birds from the pages of Audubon's

Bird-Lore.

For many students, the best part in the whole magazine was the bird biography.

“I am the Golden Plover,”

it would begin, and would go on to describe in the bird's imaginary voice how it found food, attracted mates, raised its young, and navigated its way on its long migratory flights. Every issue featured a different bird.

Bird-Lore.

For many students, the best part in the whole magazine was the bird biography.

“I am the Golden Plover,”

it would begin, and would go on to describe in the bird's imaginary voice how it found food, attracted mates, raised its young, and navigated its way on its long migratory flights. Every issue featured a different bird.

The stories were written by Professor Arthur Augustus Allen of Cornell University, a world expert in bird behavior. “Doc,” as his ornithology students called him, shared his home with his wife, Elsaâalso an ornithologistâtheir five children, one Burrowing Owl, a free-roaming crow, a family of Rose-breasted Grosbeaks, and dozens of wild ducks who bathed in the pond behind the house.

And always there were special guests. One was a young Golden Eagle that a farmer had captured and delivered to Doc's office at Cornell. Doc brought it home and put it in a pen outside. For fifteen days the great bird refused all offers of food. It turned its beak away from dead mice, scorned dead rabbits, and ignored dead chickensâit even declined fresh fish. Finally, remembering that eagles kill most of their food themselves, Doc pushed a live black hen into the pen and shut the

door. The two birds looked at each other and went to sleep side by side. The eagle soon gave up its hunger strike and ate whatever Doc gave it, but it would never touch its companion, the hen. Wondering if the eagle was no longer a predatorâa killer of live foodâDoc shoved in another hen. The door had scarcely shut before the eagle pounced on and devoured the newcomer.

door. The two birds looked at each other and went to sleep side by side. The eagle soon gave up its hunger strike and ate whatever Doc gave it, but it would never touch its companion, the hen. Wondering if the eagle was no longer a predatorâa killer of live foodâDoc shoved in another hen. The door had scarcely shut before the eagle pounced on and devoured the newcomer.

Professor Allen was always experimenting with new equipment, too, especially cameras and recording devices. In the spring of 1924, he and Edna stuffed their cameras, lenses, film canisters, and binoculars into a Model T Ford and headed south to photograph and film some of America's rarest birds. When they reached Florida they were introduced to a lean, leather-faced guide named Morgan Tindall, who said he could lead them to a pair of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers.

BINOCULARS

The need to shoot specimens lessened as it became possible to fit powerful magnifying lenses into binoculars. At first, only the wealthy could afford them, but by the 1920s even the youthful members of the Bronx County Bird Club were able to afford seven dollars each to buy mail-order binoculars that could make birds look four times their actual size. Today, lightweight binoculars can magnify images forty times and more.

The Allens leaped at the chance. The Ivory-billed Woodpecker hadn't been reported for years, and many ornithologists assumed it was extinct. But suppose it wasn'tâwhat a find that would be! With Tindall shouting directions over the engine's rumble, the Aliens gunned the car through flooded swamps. Sheets of gray moss hung from giant, widely spaced cypress trees. For seventeen long miles the Ford's wheels were completely underwater. One evening the engine sputtered to a stop and refused to restart. Miles from help, the Ford became an island in an alligator-infested swamp. To the Aliens' great relief, it roared to life again the next morning.

Tindall was right about the Ivory-bills. Just after dawn on April 12, Doc Allen peeked out from a crouched position behind a blind made of palmetto leaves, and saw two huge black-and-white woodpeckers winging through the cypress trees. Clearly showing a broad saddle of white on the lower wings, they swooped up and came to rest high on a dead pine snag. When Allen could steady his fingers, he pointed, not a shotgun, but a camera at the birds, and snapped history's first photographs of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers.

The birds called a few times and then flew off together back into the swamp. Allen sloshed frantically after them, then gave up to catch his breath and empty his boots. But that evening the birds returned, and they came again the next day, finally leading the

explorers to a dead cypress tree with a twisted snag of a top. Thirty feet above the ground was a large, freshly chiseled oval cavity. It was a nestâthat meant the Ivory-bills were still reproducing. Allen got more clear photographs and was able to describe the Ivory-bills' courtship, though he had to leave before young birds were hatched.

explorers to a dead cypress tree with a twisted snag of a top. Thirty feet above the ground was a large, freshly chiseled oval cavity. It was a nestâthat meant the Ivory-bills were still reproducing. Allen got more clear photographs and was able to describe the Ivory-bills' courtship, though he had to leave before young birds were hatched.

The sensational discovery made headlines throughout the country. Reporters turned the scholarly Allens into safari heroes. One newspaper called their trip “an expedition fraught with peril and adventure, penetrating far into the disease-infested glades of Florida in search of rare forms of bird life.” Headlines trumpeted, “CORNELL EXPERTS FIND BIRDS WITH BILLS OF IVORY” and “RARE FEATHERED FREAKS REVEALED IN UNEXPLORED FLORIDA SWAMPS.”

More important, Doc Allen came back to Cornell with nearly seven thousand photographs and 1,600 feet of motion-picture film of birds that few Americans had seen. He had added to America's knowledge of birds without ever firing a shot. And, of course, he had rediscovered the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. But just before he and Edna left Florida, a message from Tindall cast the whole expedition into a cloud of gloom. Two local collectors had been following the Allens and Tindall on their Florida quest. They knew the Ivory-bills were valuable and had asked the county sheriff for a permit to hunt them. Amazingly, the sheriff had obliged. Now, according to Morgan Tindall, the birds were gone.

So it was that the normally unflappable Arthur Allen wore a grim expression when he gave reporters a terse statement: “As long as the state of Florida allows [Ivory-bills] to he taken legally,” he said, “ ⦠the species is doomed to certain extinction.” He didn't share his personal feelings, but he must have worried that their extinction might have already occurred. Worst of all must have been the thought that he, Arthur Allen, America's only full-time professor of ornithology and a man who had dedicated his life to understanding birds in the wild, had unwittingly helped to seal the fate of America's rarest bird.

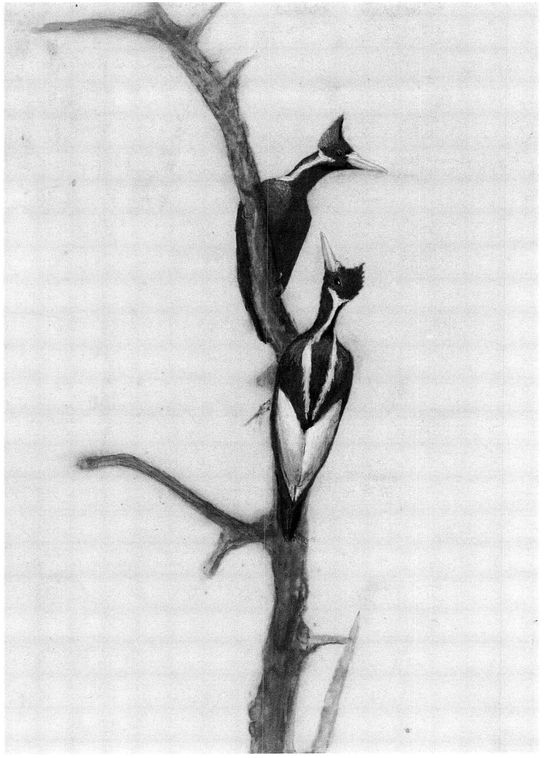

The first photograph ever takenâby Doc Allenâof the Ivory-billed Woodpecker

LEARNING TO THINK LIKE A BIRD

My best Acquaintances are those

With Whom I spoke no Word.

With Whom I spoke no Word.

âEmily Dickinson

T

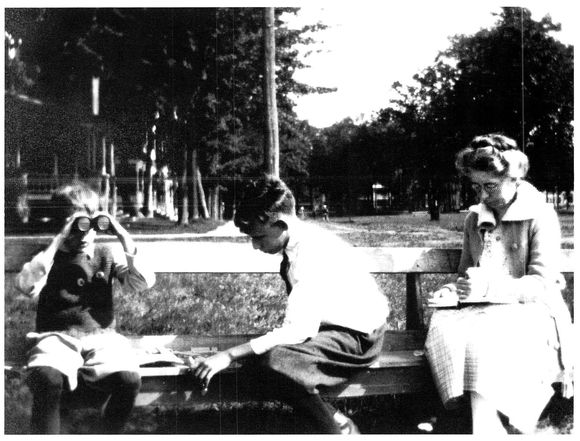

HERE IS A FAMILY PHOTOGRAPH OF JIMMY TANNER, EIGHT OR NINE YEARS OLD, SEATED on a park bench, looking out at the world through a pair of binoculars. Beside him, his tall older brother, Edward, is bent in intense concentration over a book while his mother also reads. Jimmy is in a world of his own, totally absorbed in whatever he is looking at. Odds are it was a bird.

HERE IS A FAMILY PHOTOGRAPH OF JIMMY TANNER, EIGHT OR NINE YEARS OLD, SEATED on a park bench, looking out at the world through a pair of binoculars. Beside him, his tall older brother, Edward, is bent in intense concentration over a book while his mother also reads. Jimmy is in a world of his own, totally absorbed in whatever he is looking at. Odds are it was a bird.

The slender, sandy-haired boy behind the binoculars would grow up to become forever linked to the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. He would know it best, spend the most time with it, record its voice, take the best pictures of it, and devote years of his life to trying to save it from extinction. Had he been born a few decades earlier, he might well have grown up, like Arthur Wayne, trying to study the Ivory-bill by collecting specimens. But he was a product of the Audubon movement, part of the first generation of ornithologists that learned mainly by studying how birds behaved in their natural habitats.

Jim Tanner was born in the small town of Cortland, New York, in 1914, the same year that Martha, the last Passenger Pigeon, died in the Cincinnati Zoo. The Tanners gave their two sons a well-rounded education that included a strenuous outdoor life, a

church upbringing, and exposure to mechanical skills as well as book learning. Jim could fix almost anything and invent what he couldn't. He could take complicated things apart, remember where he had laid all the pieces, and then put them back together. People told him that if he could ever think of anything useful to invent, he might get rich someday. To make themselves hardier, like President Theodore Roosevelt, Jim and Edward slept outside on a screened-in porch even on the frostiest New York winter nights. They shivered plenty, but rarely got sick.

church upbringing, and exposure to mechanical skills as well as book learning. Jim could fix almost anything and invent what he couldn't. He could take complicated things apart, remember where he had laid all the pieces, and then put them back together. People told him that if he could ever think of anything useful to invent, he might get rich someday. To make themselves hardier, like President Theodore Roosevelt, Jim and Edward slept outside on a screened-in porch even on the frostiest New York winter nights. They shivered plenty, but rarely got sick.

More than anything Jim loved the outdoors. He explored the territory near his home after school, seldom making it home “by dinner,” the family rule. On weekends he set off on long hikes, stuffing a slab of beef wrapped in waxed paper into his knapsack to cook over a fire when he got hungry. Sometimes alone, sometimes with his friend Carl McAllister, he traced the flat, low ridges around the lake country of central New York, exploring the gorges and blue glacial ponds, hauling himself up granite boulders, probing through marshes, learning to be quieter.

Like most small-town boys, Jim owned a rifle and liked to shoot it, but he never took it with him. He even refused to collect butterflies with his friends because he couldn't make himself stick pins in their wings. He wanted to meet wild things on their own terms, not his.

All nature was interesting to Jim, but nothing was as fascinating as birds. He especially loved to listen to them. He practiced imitating their songs and could sometimes get them to answer him. He taught himself which birds sang from the ground, which sounded from the middle of trees, and which called from the highest branches. He got so that he could even tell them apart by their one-note chipsâsharp little warning notes which had no melody. He learned to identify nests and eggs. He picked up owl pelletsâregurgitated wads of matter that owls couldn't digestâfrom under pine trees and used a twig to tease tiny mouse bones from the fur balls. Sometimes he hiked with a heavy camera, snapping pictures that he developed when he got home, turning the family bathroom into a darkroom.

Jim learned a lot from school, but his most valuable lessons came on those long hikes. He kept a journal, starting with the date and time of day and noting the weather and the direction of the wind. He made himself go a long time between meals. He learned to sit still against a tree even if the bark was digging into his shoulder

blades and itching like mad. Most important, he learned that while you can't meet Wildlife by appointment. if you study wild creatures carefully enough, you can predict where they will be.

blades and itching like mad. Most important, he learned that while you can't meet Wildlife by appointment. if you study wild creatures carefully enough, you can predict where they will be.

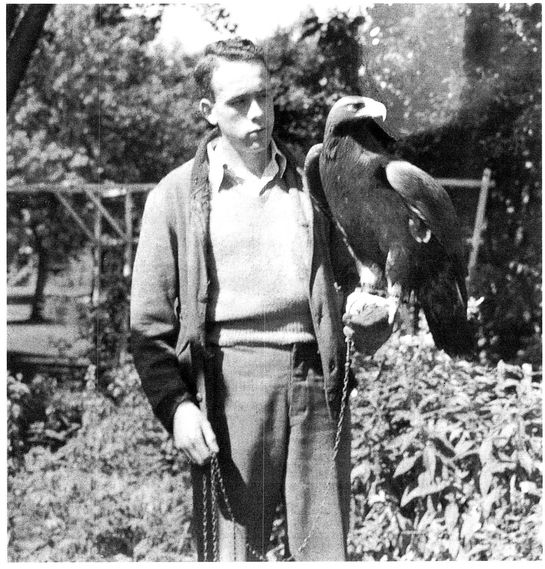

By the time Jim was a teenager, he had sailed through his scout badge on ornithology and was known as a town expert on birds. When someone picked up a wounded Golden Eagle far out of its range, he naturally took it to Jim. Jim kept it in a cage in his home and fed it rodents until it regained its strength. Then, like a falconer, he taught it how to hunt from his arm.

Jim Tanner with the Golden Eagle he rescued

As Jim Tanner entered his senior year of high school, he had many possibilities to choose from, but he had plans of his own. By the greatest stroke of luck, he lived only twenty-two miles from Cornell University, one of the world's premier centers of bird knowledge, where Professor Arthur Augustus Allen offered America's sole course of study in ornithology. That meant that Jim was only an hour's bus ride away from a chance to make his living learning about, teaching about, and helping birds. Ranked third in his class, he applied to Cornell and was quickly accepted.

By the time he said goodbye to his family in the late summer of 1931, Jim Tanner was almost as much a creature of the forest as any songbird, and as hungry for knowledge as an owl for a mouse. At last he was headed to Ithaca, New York, to study with the world-famous Dr. Allen at Cornell. No more “be home by dinner” for him. From now on, dinner would be whenever he could find time to eat.

OLD MCGRAW

The center of every Cornell ornithology student's universe was McGraw Hall. When people stepped into the creaky building from the often snow-covered campus, their eyes had to suddenly adjust to the dim light even as their nostrils filled with the sharp odor of formaldehyde. Jammed into McGraw's three noisy floors were dozens of small classrooms, offices, closets, and even a museum. Bird skeletons raised their wing bones from dusty windowsills. Stuffed hawks and owls and shorebirds stared silently from every nook and cranny. Pickled bird parts floated lazily in briny jars that rested on shelves in laboratory rooms.

THE ROUGHING-OUT ROOM AT MCGRAW

If you want to learn about birds, you have to get to know bugs, since birds of almost every family eat insects and spiders. At McGraw, the “Roughing-Out Room” high in a drafty tower of the old building was the place where students took notes as hordes of beetles attacked the crudely skinned corpses of birds and animals, breaking them down into skeletons which were then studied further.

Cornell professor George Sutton wrote: “In the roughing-out room, the fumes of ammonia are so strong as to be all but overpowering. Had Edgar Allan Poe spent two minutes in this chamber of horrors, he might have written a mystery thriller the likes of which are not on the world's bookshelves today.”

Bird students investigated and experimented all day and all night. Many projects involved getting to know more about what birds ate. Live bullfrogs splashed in McGraw's sinks, and field mice scraped their claws against the slick sides of big tubs kept in the lab rooms. There were refrigerators containing

dead cats, and gunnysacks stuffed with dead hawks and owls whose stomachs awaited examination. One student even had his own collection of snakes, at least until the day they all got loose. For months afterward, bloodcurdling screams rang out through the building. After a while, students didn't even notice. Screams only meant that someone had encountered a Blue Racer coiled behind a specimen flask, or maybe that a blacksnake had dropped onto a student's open textbook from a library shelf above.

dead cats, and gunnysacks stuffed with dead hawks and owls whose stomachs awaited examination. One student even had his own collection of snakes, at least until the day they all got loose. For months afterward, bloodcurdling screams rang out through the building. After a while, students didn't even notice. Screams only meant that someone had encountered a Blue Racer coiled behind a specimen flask, or maybe that a blacksnake had dropped onto a student's open textbook from a library shelf above.

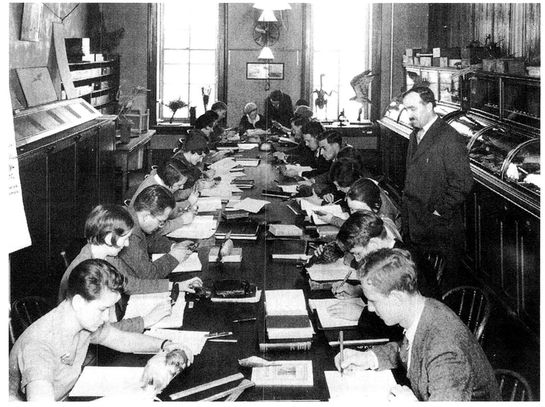

Doc Allen oversees a Cornell ornithology class at McGraw Hall. Note the bird skeletons on the windowsill

In 1931, the Great Depression created widespread poverty and made it hard for many families to send their children to college. Doc Allen did everything he could to keep his bird students in school, including letting a few of them live at McGraw. One young man from Florida, having no money to rent a room, unrolled his mattress each night on top of a long classroom laboratory table and fell asleep. The students who opened the door for early-morning lectures sometimes startled him awake, causing him to scramble into his trousers and dive behind a cabinet to shave. He cooked his dinnerâusually a stew of carrots, beans, and bread crustsâin a big pot, adding the

bodies of whatever Red Squirrels and chipmunks he was able to trap on campus that day.

bodies of whatever Red Squirrels and chipmunks he was able to trap on campus that day.

Jim Tanner, with financial help from his family, moved his belongings into an all-male rooming house which provided a bed and dinner for five dollars a week. It was all he needed. For Tanner and his fellow ornithology students it was birds, birds, birds, almost twenty-four hours a day. He took classes in entomology (the study of insects), zoology, and German, a language in which many articles about birds were written. He also studied drawing, bacteriology, botany, and genetics. He especially liked Professor Allen's new course, “Conservation of Wildlife,” which explored how to preserve wild species in their natural habitats. It was the first such course in the United States.

Every Monday night, Tanner stomped into McGraw with his classmates, his professors, and invited guests for the week's discussion on birds. The seminar sessions began with each person telling the entire group about the birds he or she had seen on campus in the past week. It was a chance to shine before the others, or to make an embarrassing mistake out loud. Doc, who led the group, never reacted to errors in bird identification with laughter or harsh words, but instead with gentle questioning and thoughtful remarks, which could be even worse. A student named Sally Hoyt Spofford remembers reporting a Swamp Sparrow in March, far too early for the bird to be in Ithaca. The others looked down at their boots and tried to conceal smiles as Sally's face reddened. “How interesting,” Dr. Allen mused, his voice light. “That

is

an early one.”

is

an early one.”

Tanner pushed himself hard, learned rapidly, and won high marks. He flew through a four-year course in just three years. In the spring of 1934, when he was finishing his undergraduate studies and wondering what to do next, McGraw was buzzing with rumors and wagers about how Doc was going to spend his sabbatical leave. Doc had taught at Cornell for more than twenty years without a long break. In that time, he had made Cornell a world leader in the study of birds. At last he was going to get six months to study whatever he wanted.

Most predicted it would have something to do with bird sounds. In 1929 a Hollywood movie studio had called Doc to see if Cornell could provide background birdsong for a film. Doc had no library of recordings to offer, but he had been so

fascinated by the possibility of recording for the movies that he had invited the filmmakers to Cornell to try to record some birds. In those early days of talking movies, the only way to record sounds was by filming them on “motion picture sound film” with “sound recording cameras.” You actually played the sound back on a screen. That spring a Hollywood crew drove to Ithaca in a truck bulging with thirty thousand dollars' worth of recording equipment. They picked Doc up at the Cornell campus and rumbled straight to a city park to see if they could record birds that were singing there.

fascinated by the possibility of recording for the movies that he had invited the filmmakers to Cornell to try to record some birds. In those early days of talking movies, the only way to record sounds was by filming them on “motion picture sound film” with “sound recording cameras.” You actually played the sound back on a screen. That spring a Hollywood crew drove to Ithaca in a truck bulging with thirty thousand dollars' worth of recording equipment. They picked Doc up at the Cornell campus and rumbled straight to a city park to see if they could record birds that were singing there.

The men staggered around the park beneath heavy cameras and microphones, usually scaring the birds away before they could get near. But they did manage some film, and when they ran it back at McGraw, they could faintly make out the scratchy voices of a Song Sparrow, a House Wren, and a Rose-breasted Grosbeak. Doc heard the future in those sounds.

For the next few years, Doc and an ever-growing group of students kept experimenting with ways to record birdsong. At the center of the action was Albert Brand, a pudgy stockbroker from New York City who had quit his Wall Street job to study birds at Cornell. Brand used his wealth to buy recording machines that he, Doc, and three engineers tinkered with day and night. They cranked up the volume as loud as they could to make the faint bird voices come out. A professor whose office was next to the laboratory where the experiments were being carried out described hearing “the wildest of yells, roars, crashes and shrieks as dials are turned and films projected. Lowered in pitch and augmented in volume, the recording of a yellow warbler's cheery little voice sounds for all the world like coal roaring down a chute into somebody's cellar.”

THE SOUND MIRROR

One afternoon, Cornell ornithology student Peter Keane, in New York City on a break, wandered over to the construction site of Radio City Music Hall. He found it interesting that giant parabolic reflectors were being installed as part of the sound system. These huge, dish-shaped devices were used to concentrate and amplify sound, and to screen out unwanted noises.

Keane asked himself if the reflectors might not work on a smaller scale. What if you built smaller, portable reflectors that you could carry by hand to a bird's nest? The Cornell physics department just happened to have in its attic a mold that had been used to build parabolic reflectors during World War I to detect enemy planes. Keane and his fellow student Albert Brand used it to build a big, shiny dish they called a “sound mirror.”

One morning they carried it out into a field, set it on a tripod, suspended a microphone in the middle of the dish, and aimed it at a singing bird. It worked. Most of the usual background noise, such as barking dogs and rushing rivers, was goneâand the birdsong was loud and clear.

Within two years, Brand and fellow Cornell student Peter Keane had recorded forty bird species. It was Brand who finally came up with the winning idea for Doc's sabbatical leave: why not tour the country, recording the voices and filming the

behavior of America's rarest birds? Then Americans could hear their songs and see them move

before.

they became extinct. A Cornell team could install the new sound equipment in a truck like the one from Hollywood. Brand himself would raise the money. They would work in the spring, when birds would be singing loudly to attract mates and defend their breeding territories.

behavior of America's rarest birds? Then Americans could hear their songs and see them move

before.

they became extinct. A Cornell team could install the new sound equipment in a truck like the one from Hollywood. Brand himself would raise the money. They would work in the spring, when birds would be singing loudly to attract mates and defend their breeding territories.

Doc loved the plan. He had long regretted that people could no longer hear the Passenger Pigeon's coo, the toot of the Heath Hen, the Labrador Duck's quack, or the Great Auk's grunt. These were sounds Americans had once known well. Now, because these birds were extinct, their songs had passed forever from human memory. Other birds were in danger of slipping away, too. Brand's idea could preserve their voices before they were lost. And if they succeeded, Cornell would be known as a world leader in sound.

Of course, there was another reason for Doc's enthusiasm. He had never forgotten the two Ivory-billed Woodpeckers he and Elsa had seen in Florida back in 1924, the birds that had been shot soon after. There had been no more confirmed sightings of Ivory-bills since. But suddenly there was hope again. Doc had learned that in 1932 a lawyer named Mason D. Spencer had found and shot an Ivory-bill in a Louisiana swamp. Ornithologists had rushed to the scene and found several more Ivory-bills nearby. Recording the birds on film would give Doc a second chance, a different way to “collect” these beautiful phantoms without killing them. Doc wanted to study their life cycle and to see if somehow the species could be preserved in its natural setting before it was too late.

Allen told reporters that the “BrandâCornell UniversityâAmerican Museum of Natural History Ornithological Expedition” would be a new kind of “hunting” expedition whose members would “leave guns at home and would âshoot' the birds with cameras, microphones, and binoculars.”

The idea caught the imagination of both the public and the scientific world. According to one newspaper article, “Never before in the world's history has any expedition started afield with so highly sensitive equipment.” Cornell was flooded with applications from scientists, curators, and bird-watchers who wanted to go along.

While Brand raised funds and Cornell professor Peter Paul Kellogg installed the recording machines in a truck, Doc recruited the team he wanted: Doc himself

would film and photograph the birds, Brand would pay the bills and help work on sound, and Kellogg would operate the equipment at the truck, while George Sutton, a sharp-eyed bird artist, would help identify birds and scout for sites.

would film and photograph the birds, Brand would pay the bills and help work on sound, and Kellogg would operate the equipment at the truck, while George Sutton, a sharp-eyed bird artist, would help identify birds and scout for sites.

But Doc needed one more person. It had to be someone who knew birds and who possessed the strength and agility to do the heavy work of the project, someone who could climb trees like a monkey. Whoever it was would have to be cheerful enough to take orders from cranky professors at five in the morning. This person would have to be able to fit in with everyone, for surely the team would meet people around the United States whose views and ways clashed with theirs.

In the end, it wasn't a hard decision at all. As Doc put it in the press release that went to newspapers, “James Tanner, graduate student, was invited to accompany the expedition as handy man to act in any necessary capacity.”

Jim Tanner operates Cornell's newly designed sound reflector, or “sound mirror,” hoping to hear an Ivory-bill

Other books

Learning the Hard Way by Bridget Midway

Charades by Ann Logan

Yom Kippur as Manifest in an Approaching Dorsal Fin by Adam Byrn Tritt

Irish Seduction by Ann B. Harrison

What Really Happened by Rielle Hunter

Dear Miffy by John Marsden

One Lucky Lady by Bowen, Kaylin

Fire and Rain by Lowell, Elizabeth

SAMANTHA POSEY: LOVE UNFOLDED: A BWWM Alpha Billionaire Romance by Shantee' Parks

The Wonderful Adventures of Nils Holgersson by Selma Lagerlöf