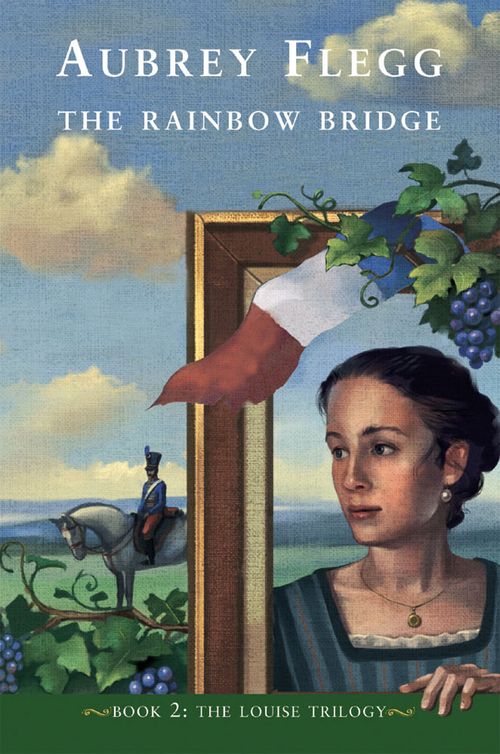

The Rainbow Bridge

Read The Rainbow Bridge Online

Authors: Aubrey Flegg

The Rainbow Bridge

Praise for The Rainbow Bridge:

‘An original, interestingly-imagined and challenging book. Its finely-textured writing with historical flavour and a strong plot make this a rare achievement.’

The Irish Times

‘Flegg is one of the finest writers of children’s literature in Ireland today. Many passages in this novel are a pure pleasure to read.’

Inis

Praise for Wings Over Delft, Book 1 in the Louise trilogy:

‘A remarkably engaging story, in which themes of love, art and history are powerfully combined. The unfolding narrative is dramatic, passionate and brilliantly set. The quality of the writing throughout is superb and the ending unforgettably moving.’

Robert Dunbar, critic and broadcaster

‘The gentle love story takes the reader through dark intrigue, religious unrest and the palpable, cultural atmosphere of life in a Dutch city, to an unexpected conclusion. A well-tailored and absorbing read for adults as well as for age 12-plus.’

The Sunday Tribune

‘Flegg gives us an exquisitely crafted novel which will stay in the reader’s memory long after the closing pages are read. The ending is unexpected and dramatic and leaves the reader eagerly awaiting the subsequent books in the Louise trilogy.’

Valerie Coghlan, Inis

Book 2 : the

Louise

trilogy

Aubrey Flegg

The

Louise

trilogy is dedicated to Bill Darlison

Even the rainbow has a body made of the drizzling rain and is an architecture of glistening atoms built up, built up yet you can’t lay your hand on it, nay, nor even your mind.

‘The Rainbow’,

D H Lawrence

.

The

Rainbow

Bridge

is dedicated to Jennifer

I am deeply indebted to my family and to my friends for their help, advice and support during the writing of The Rainbow Bridge, not all of whom can be listed here. My love and gratitude to Jennifer, my wife, who has picked me up and dusted me down when I have tried to climb on rainbows. To Patrick and Margaret Kelly who, with Jan de Fouw, read my early draft and have shared with me their knowledge and wisdom, my grateful thanks. Any errors that may have crept in are of my making. A special word of thanks to Louise Fitzpatrick, and to my younger reader, Sam Fitzpatrick (no relation), who between them gave me warning when my last chapters were going astray. My thanks to Nicolas Canal whose spirited singing of ‘The Marseillaise’ convinced me that that song alone could quell any mob.

Then there are my thanks to all at The O’Brien Press who have provided me with cheerful encouragement throughout. My personal debt to Michael O’Brien is but a reflection of the debt owed to him by everyone involved in children’s literature in Ireland. Thanks also to Íde ní Laoghaire, and to all of the production team, particularly Emma Byrne for her cover design. Now a very special word of thanks to Mary Webb, my editor: thank you Mary, they never said it was going to be easy, but you kept with me every step of the way with your attention to detail, encouragement and ideas.

Finally my thanks to Bill Darlison for our many discussions, agreements, and to a lesser extent, disagreements. From Bill I have learned that living with questions is sometimes better than living with answers.

On 12 October 1654 at half past ten in the morning, Willie Claes, the watchman at Delft’s gunpowder store, absentmindedly placed a still-burning tobacco pipe in his pocket before he returned to his duties. Minutes later, an explosion took place that tore the heart out of the small Dutch town; it levelled over two hundred houses, and wiped out whole families in the process. Among the dead was sixteen-year-old Louise Eeden. The only record of her was her newly painted portrait, which survived, knocked askew on its easel in the studio of Master Jacob Haitink. Over a century would pass before the Master’s picture would be rediscovered and Louise would begin once again to affect the lives of othe

rs.

‘Ta, ta, taaa ta, Taaa ta, ta …? Ah zut! I so nearly have it. That tune has been in my head all night … Is there more coffee?’ Gaston hardly noticed as Colette got up quietly and refilled his cup for him. They were sitting at breakfast in the cavernous kitchen of the old winery, grouped about the end of the long table that could seat twenty or more vineyard workers when the season demanded it. The elegant rooms in the front of the house, which faced onto the street, were seldom used. Gaston abandoned his musical efforts and leaned back comfortably in his chair. He looked benignly around the table, consciously absorbing the details of the room and the company, as someone does who is about to leave home. Facing him was his father, chief winemaker – vigneron – to the Count du Bois who owned the vineyards that lined the gentle valley in which their village nestled. Even the village name reflected its history: Les Clos du Bois, the vineyards of the Count du Bois. His mother was sitting at the head of the table, straight-backed, looking every bit the aristocrat, which, by birth, she was.

Gaston wondered anew at the contrast between his parents. Papa’s face was deeply lined, his skin burned to mahogany from long exposure to wind and sun, making him look older than his forty-five years, but his eyes sparked bright from within the mesh of wrinkles. At the moment he was

quietly crumbling the bread beside his plate, his mind far away, probably fondling the grapes that were now swelling to their vintage ripeness under the August sun. He would hold long conversations with his vines, addressing the grapes as if they were a recalcitrant class in school and he their teacher, but he was no fool. The vineyards were his life; when he drank he was like an artist standing back from his work so that he could view it as a whole. As he rolled the wine about on his tongue, his eyes would be seeing the slopes and grapes from which its various flavours sprang, and his ears would be listening to whispered histories of sun and soil, of sudden rain, and deep fermentation. He would hear confessions too: grapes picked too soon – a musty cask – the follies of youth, and like a benign priest, would admonish, and very occasionally, condemn.

For all that he was a dreamer, it was he who, years before, had surprised everyone by carrying off the Count’s beautiful cousin to be his wife. And it was to him that the villagers came to relieve themselves of their personal burdens. If they needed straight advice they went to Monsieur Brouchard, the miller, but if they wanted a sympathetic ear they would slip in through the winery gates and seek out Monsieur Morteau among the vines or in the cellars. Gaston would see them deep in conversation and would know to keep away. Between them, Papa Morteau and M. Brouchard knew about most of what went on in and around the village.

Gaston tried to take it all in: his family, his home. Today he would leave them, perhaps never to return, and he must preserve this memory. He was eighteen and it was high time that he went, before the soil caught him and rooted him forever. A soldier’s life would be far more exciting. ‘Officer Cadet Gaston Morteau!’ he smiled, imagining

himself in the magnificent uniform that was waiting for him upstairs in his bedroom. In it he would be transformed, rising like a phoenix from the ashes of his former self. And he would be fighting for the noblest cause: the defence of his country.

It had been three years since the storming of the Bastille in Paris, when the people had turned against the King and the aristocracy, and begun the Revolution that had swept through France. Castles were burned, noble families were attacked and many emigrated in fear. The arguments for and against the Revolution had swept back and forth around the Morteau table, as in most homes throughout France, with Madame defending the ‘noble privileges’ and the order imposed by the aristocracy, while Gaston would defend the rights of the people. However, in truth, the village was too out of the way for the turmoil to have had any real effect on them so far.

But now it was different; the Prussians had crossed the border, determined to restore the King to the throne. Gaston’s beloved France was under attack, and today he would set off to join the Hussars of Auxerre in their fight against the enemy. As he thought about what might be ahead of him, he wanted to spread his arms and embrace this dear place, his home, and his family.

And so it happened that, still smiling, he looked up and found himself staring into the eyes of Colette. She saw his smile, half returned it, and then dropped her eyes. Gaston felt a stab of guilt. Though the girl had been in the house for nearly six months, he’d hardly noticed her; she was only fourteen, four years younger than he. The poor child’s father had been killed just three years ago in Paris in ’89, at the very beginning of the Revolution. Hearsay had it that her father had intervened – as he would have done to help

anyone in distress – when two elderly aristocrats had been pulled from their coach by the mob. No one knew precisely what had followed. The bodies of all three were found later, and there were no reliable witnesses. Then, last March, the girl’s mother, who had been a particular friend of Madame Morteau, had died, and Colette de Valenod was quietly absorbed into their family. It was a tricky time; some of Colette’s relatives were under sentence for their royalist sympathies, so the aristocratic ‘de’ was dropped from her name. For some months Madame had kept her virtually under house arrest, now it was put abroad that she was a distant cousin of the Morteau family.

Colette was staring straight ahead now, her wrists resting dutifully on the edge of the table, head slightly forward so that her dark hair hung loose, part-curtaining her face. She looked lost and vulnerable, the half-smile gone, replaced by the sadness that was her customary demeanour. Gaston’s newfound gallantry obliged him to try to restore that smile. This was a day when he wanted everyone to be happy. As if she felt the intensity of his look, hot colour suddenly washed across Colette’s face. Gaston picked up his coffee and blew on the surface to cool it.

‘Ta, ta, taaa…’ he began again.

Colette’s head lifted.

‘It is rude to sing at table,’ his mother interrupted him. ‘And I don’t think much of the words either.’ But behind the criticism there was a glimmer of a smile.

‘Oh, I know the words, Maman. I have them by heart; it’s just the tune I can’t get. I heard it when I went to be fitted for my uniform in Auxerre. It was brought to Paris by a battalion of volunteers from Marseilles, so they call it the ‘Marseillaise’. You will love it – all about country, and patriots, and blood.’

‘Blood?’ his mother snapped. ‘Why does it always have to be blood? And the poor King, what will happen to him in prison, and Marie Antoinette … and the boy?’

‘They are safer where they are, Mother.’

‘No! I don’t trust those Girondins, what they really want is to do away with the monarchy and have a republic instead. And why did they have to massacre the King’s Guard? In their lovely uniforms!’ For all that Mother had married a commoner she was still an aristocrat and a Royalist at heart. She and Gaston would spar together as a matter of routine. ‘What was it all for?’ she asked.

‘Mother, the King was in league with our enemies; it’s not just the Prussians, half the countries of Europe are lining up to put him back on the throne and put the nobles back in their castles. Do you know what the Duke of Brunswick, the general who is leading the invasion, says? He says that when he liberates the King he’ll execute the entire population of Paris? That’s blood for you.’

‘Well, what have you to offer that is better than the nobility?’ she challenged.

‘Liberty, equality, and fraternity – “The Rights of Man!”’

‘They have just copied those from the Americans,’ Madame Morteau sniffed. ‘We should never have supported them against the British in ’78; you won’t remember it, you were just four, but I do. Now look at the monster it has unleashed, and on our own soil.’

‘But it needn’t be a monster, Mother. ‘The Rights of Man’ is our constitution – that all men are born free and equal! We should know these rights by heart: Liberty, Property, Safety, and Resistance to Oppression. Sovereignty lies in the nation, whether we have a king or not. Don’t you see that we are changing the face of Europe? France will stand out as a beacon of hope!’

It was familiar territory to them all. Every once in a while Gaston and his mother had to go through this ritual combat. Even though Father never joined in, Gaston had the uncomfortable feeling that he had a clearer view of the situation than had either of them.

‘I don’t see anything noble in the common man when he becomes a mob,’ Madame Morteau said, tight-lipped. ‘Halfcrazed, uneducated masses striking down innocent people.’

‘That’s why we need an army, Mother – disciplined soldiers.’ Gaston, impressed by his own rhetoric, put his hand to his chest. Here he was, setting out to take up arms for his country, to lay down his life for these people: Mother, Father, Colette, the people of the village …

His fine thoughts were cut short by his mother. ‘Have you forgotten that the Count is coming today?’ she asked.

Gaston removed his hand. The Count du Bois usually made an appearance in the village on church holidays, and used these occasions to call at the winery and discuss business with Gaston’s father.

‘He wants to see you in your uniform before you go.’

‘My dress-uniform?’

‘Of course, what else?’

‘Mon Dieu, Maman … I don’t even know how to put it on!’

‘I don’t think he’ll be critical. He didn’t pay for it,’ Madame Morteau said acidly. The Count, though noted for charm, was notoriously careful of his purse. ‘Don’t worry, he will feel that his letter of recommendation to your colonel deserves your homage.’ While Mother would defend the aristocracy in principle, she gave no quarter when it came to the faults of individual aristocrats, her cousin in particular.

‘Will you tell him that you want to buy out that portion of the vineyard that is due to you?’ Gaston asked, changing the subject. When his mother had married, part of her marriage settlement had been the right to buy a significant portion of the vineyard from the Count, if she so wished. Papa, however, had steadfastly refused to countenance this. His family had managed the vineyards for the Chateau du Bois for generations; he was an artist and a craftsman, not a landowner. As the Count’s vigneron he had the virtual management of the whole valley. The vineyards were his palette, and the wines he created were his pictures. The idea of carving the vineyard up, even to his own advantage, was abhorrent to him. He needed the full palette of colours to create the richness and variety of his wines.

Gaston could see his father shifting uncomfortably in his chair. He felt bad about raising the matter, but with all that was going on in France at the moment, there were no guarantees that the Count would be left in possession of his vineyards. What would happen to Mother’s entitlement if the Count fled, or had his land confiscated? If there were no chateau vineyard, who would employ them?

‘You know your father doesn’t want that,’ his mother said with resignation. On matters of principle Father could be immovable. He was getting to his feet now, brushing the crumbs from his shirt.

‘No, Gaston. The vineyard is a living thing; it cannot be divided. Each vine, each slope, each acre plays its part in every barrel we produce. I will not destroy what it has taken generations to make as one. The Count has declared for the Republic, he supports the Revolution, and nobody in the village will make any trouble. Our roots are with the chateau.’

Colette helped to clear the table when the meal was over and then joined Margot, the kitchen maid, in the scullery to dry the breakfast cups. She needed to do something practical with her hands. She had been acutely aware of Gaston’s stare at breakfast. It felt as if she had walked on to thin ice and felt it cracking beneath her; she found the experience both disturbing and exciting. She wanted to be happy, but whenever she responded to Margot’s light-hearted banter she could feel Madame’s disapproval, reminding her that she was still in mourning. There was a lot about this family that Colette didn’t understand. At one minute she would represent a welcome pair of hands in a busy household, but in the next she would feel that she was being preserved as some sort of relic of her poor mother. What she needed now was the practical clatter of plates, and to hear the latest round in Margot’s bid for the heart of Lucien, a worker at the flourmill down by the river. Margot was almost her only contact with the village; Madame kept her so secluded – for her own safety – that she had met hardly anyone outside of the winery. She hurried into the scullery where she found Margot simmering with indignation like a saucepan about to blow its lid.

‘Oh, Mademoiselle! You have come at last. I am ready to explode.’ Margot opened her eyes to a startling extent. ‘Wait till I tell you. Lucien, le cochon … the pig… he swore to me that Bernadette meant nothing to him.’ Bernadette was Margot’s rival in the battle for Lucien. ‘The cow … she is a slut! Yesterday as I approached the mill I saw someone coming out. “Who is this coming towards me?” I ask myself.’ Margot was shortsighted. ‘My heart beats faster. Oh! No need to worry … it is just la Bernadette, “Pah!” I say to

myself. I raise my nose in the air until she is past.’ Margot imitated her own nonchalant walk. ‘This woman, she means nothing to Lucien therefore she means nothing to me. I wait till she’s past, then I turn to her back and I put my tongue out like this. Ohhhhhh la la, Mademoiselle what did I see?’ Margot grabbed Colette’s arm with a sudsy hand. ‘No wonder she looked like a cat with cream … merde!’