The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (23 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

At this point the Indians approached Horace Clarke, although his appearance in the record at this time—seven years after Heavy Runner’s heirs had initiated their case—invites scrutiny. Presumably, Clarke’s testimony would have been invaluable from the start, considering his role in the slaughter and his status as a mixed-blood (which meant that his voice would carry more weight in Washington than that of deponents of pure Indian ancestry). And unlike Joe Kipp, Clarke could provide key information about the military perspective on the engagement unalloyed by any obvious conflict of interest. Given the dogged efforts of the plaintiffs in marshaling evidence to support their claim, perhaps Clarke both received and rebuffed prior requests for his involvement. At the very least, it seems that he did not volunteer any assistance before 1920.

Whatever the circumstances behind its origin, Clarke’s brief statement—sworn before a notary public at East Glacier Park on 9 November 1920—was remarkable for its candor. Clarke began by acknowledging his participation in “the Baker fight,” as he called it, and moved quickly to stress the injustice of the killings that day, explaining, “[I] personally knew Heavy Runner, a good Indian and a friend of the white people.” If the numbers Clarke gave in his statement that day were unhelpful to the plaintiffs (he cited 150 dead Indians and only 1,300 confiscated horses), he nevertheless bolstered their allegation that the army’s attack upon their father’s camp was a tragic mistake. As proof, he stated for the record what had long been merely rumored: “It is an undeniable fact that Col. Baker was drunk and did not know what he was doing. The hostile camp was Mountain Chief’s, and it was the camp we intended to strike, but owing to too much excitement and confusion and misinformation the Heavy Runner camp was the sufferer and the victim of circumstances.”

114

The claimants undoubtedly thought their case stronger than ever. After all, with Clarke’s deposition they now had the support of a man who had stood on the bluffs at the Big Bend that awful morning and fired into the sleeping camp, a man who was not looking for absolution and who in fact had reason to despise the Piegans, even if their blood was his own and he had lived among them all his adult life. Armed with the new information, Senator Thomas J. Walsh of Montana, soon to become famous for leading the investigation into the Teapot Dome scandal, wasted no time in putting a bill before his chamber, introducing S. 287 just five months later, on 12 April 1921. Nevertheless, the result this time was worse than before: the proposed legislation was not even referred to the Interior Department for consideration.

115

For those who had lost the most on the darkest day in Blackfeet history, there would be no restitution, no apology, not even an acknowledgment of their suffering.

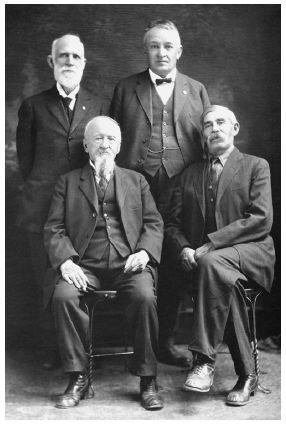

Horace Clarke et al. 1923. Taken in a Helena studio after their reenactment of a footrace from some fifty years before, this photograph shows Horace Clarke (seated at right) and David Hilger (standing at right), along with two other friends, a reminder that for Montana’s old-timers the boundaries of race were more elastic than for later white arrivals. Courtesy of the Montana Historical Society.

F

OR THE HEIRS

of Heavy Runner, the unsuccessful claim against the government perhaps brought an official closure to the Baker Massacre, but the suit marked a new beginning of sorts for Horace Clarke. In the last decade of his life, he engaged with the slaughter’s aftermath, at least publicly, in a way he never had before. Of course, there was his lengthy interview with Martha Plassmann, but a more symbolic and touching moment came three years earlier.

In September 1923 Clarke traveled from East Glacier Park to Helena in order to meet an old friend, David Hilger, who had recently moved back to the capital after an absence of four decades. The two were joined there by Andrew Fergus—who, like Hilger, was descended from a prominent white family with deep roots in the state—as well as William “Billy” Johns. During their reunion, the men reenacted a celebrated footrace they had run nearly fifty years before, although the youngest among them (Hilger) was now sixty-five. Afterward they took a photograph together in a local studio.

116

The highlight of the men’s gathering, however, was a side trip they made to the former Clarke ranch in the Prickly Pear Valley.

117

It had been so long since Horace had last visited the place that the wooden fence surrounding his father’s burial site had long since decayed. Struck by the poor condition of the grave, Clarke—with the assistance of Hilger, newly appointed librarian for the Montana Historical Society—arranged for the construction of a sturdy, wrought iron enclosure the next year.

118

As for a headstone, Clarke left it for the people of the state to erect a suitable monument commemorating, as he put it, “one of the greatest of Montana pioneers and a kind and good father.”

119

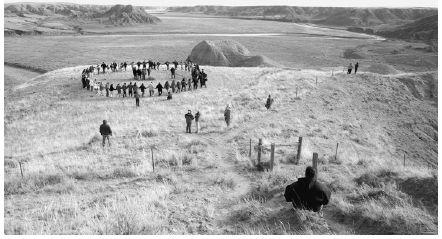

Marias Massacre commemoration, 2006. Each year, students and faculty from the Blackfeet Community College in Browning travel to the site of the Marias Massacre, where they remember those killed on 23 January 1870. Courtesy of Harry Palmer.

The fence around the grave of Malcolm Clarke still stands today, even if worn and rusted, but the only memorial is a small stone tablet, suggesting perhaps that by the 1920s the citizens of Montana preferred to forget the brutal events that had preceded them by half a century. Likewise, there is no historical marker at the Big Bend, though for many years now a group of faculty and students from Blackfeet Community College have made the sixty-five-mile trek from Browning to the site of the massacre each 23 January. On one occasion they placed 217 stones in a circle to commemorate those who died at this now somnolent patch of land, where the dark waters of the Marias form a graceful horseshoe before running east again.

120

O

n a midwinter day in 1911, Helen Clarke wrote a most unusual fan letter to Edwin Milton Royle, then a noted American playwright. At the time Royle was nearing the apex of his career. His most famous piece,

The Squaw Man

, had just concluded its third run on Broadway, and three years later it would be made into Hollywood’s first feature-length film, marking the directorial debut of a struggling former actor named Cecil B. DeMille.

1

Clarke, however, was not writing to lavish praise on

The Squaw Man

or even as a devotee of the theater (though she had once enjoyed a brief but acclaimed New York stage career herself). Rather, she sought out Royle to share her powerful reaction to the play’s sequel, a novel published in 1910 titled

The Silent Call

, which for her had captured so well the complexities of life on an Indian reservation. This feat was no accident. While Royle was a Princeton graduate and a longtime resident of the East Coast, he was, in his words, a “Western man,” raised near Kansas City, Missouri. To honor his roots, he even named his sprawling estate in Darien, Connecticut, the Wickiup (another word for wigwam). In short, Royle knew the West intimately.

Helen P. Clarke, 1895. This studio portrait, taken in New York between her stints as an allotting agent in Indian Territory, gives a sense of Helen Clarke’s commanding presence, which fueled her brief but acclaimed stage career in the 1870s. Courtesy of the Montana Historical Society.

From her own life experiences, Clarke recognized the characters and themes in

The Silent Call:

the corrupt Indian agent, the caring but naïve missionary, and particularly the simmering tensions between native peoples and their white neighbors who coveted the Indians’ natural resources. Especially poignant for Helen was the dilemma of the novel’s protagonist, Hal Calthorpe. Like Helen, Hal was the mixed-blood child of a noted white man and his Indian wife and, like Helen, had enjoyed a remarkable career for someone of such lineage. Most of all, just like Helen, Hal had felt the sharp sting of racial prejudice. Indeed, in one of the novel’s most memorable scenes, Hal recoils when assaulted with the epithet “half-breed.”

As Clarke explained in her letter to Royle, she hoped that his book might alert others to the plight faced by mixed-blood individuals. But she was doubtful, given the attitudes of “the poor white trash and the half civilized Westerners who believed that [an] Indian could be called good only when dead.” She marveled that such vitriol was matched by a toxic combination of ignorance and hypocrisy, which allowed “the so-called American, a mixture of so many breeds [and] nationalities [to] sit in the seat of the scornful and arrogate to himself a pureness of blood, a superiority, something of which he is so unworthy an exponent.”

2

In a prompt and generous reply, Royle likened racial prejudice to superstition, but acknowledged that “we are all more or less tainted with it,” noting ruefully that his own grandfather had been a slave owner. Still, he saw cause for optimism, insisting that the progress of the age—steam, electricity, the telephone—would bring people closer together and thus erode, however slowly, the fear and hatred stemming from perceived human difference. To boost her spirits, he even recommended a recent book by a French writer that attacked the notion of fixed racial inferiority.

3

Regardless of his mollifying words and thoughtful reading suggestions, Royle could not do for Clarke what he had for Hal Calthorpe: provide a happy ending. All turns out well for the hero of

The Silent Call:

Hal secures his father’s vast landholdings on the northern Plains, wins the affections of a beautiful Indian girl, and even earns the lasting respect of local whites. Clarke, on the other hand, could only dream of such a tidy resolution. For a mixed-blood woman, even one as arresting and accomplished as Helen Clarke, the racial, gender, and social politics at the turn of the twentieth century—an era she bitterly denounced as “the Age of Tribes”—produced far more ambiguous resolutions.