The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (30 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

N

early seven decades after Helen Clarke’s death, the Montana Historical Society (MHS) mounted a lavish retrospective in 1993 featuring the work of her nephew John L. Clarke, a woodcut artist with a remarkable biography. Descended from one of the state’s oldest pioneer families, Clarke had overcome the inability to hear or speak and established a career as an internationally acclaimed sculptor, known especially for his extraordinary renderings of western wildlife. As one admirer recalled, “When John L. Clarke finished carving a bear, you could just smell it.”

1

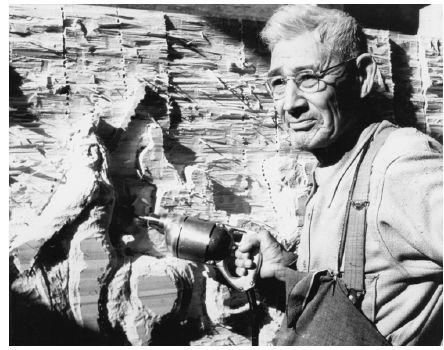

Highlighting the Helena exhibition was the unveiling of a splendid bas-relief frieze. Carved from a one-ton block of cottonwood,

Blackfeet Encampment

captures the essence of the tribe’s lifeways in the period before Montana’s absorption by the United States. Accompanied by their dogs, a group of Indians on horseback arrives at a small stand of teepees, whose residents emerge from their lodges to greet the newcomers. A herd of ponies grazing in the distance speaks to the prosperity of the camp, while a kettle suspended over an open fire holds the promise of nourishment for the weary travelers. It is a moving scene, conveying the unmistakable impression that all is right with the world.

John L. Clarke and

Blackfeet Encampment

, ca. 1950s. Clarke carved his masterpiece on-site at the Montana Historical Society, using both traditional and contemporary tools. Courtesy of Joyce Clarke Turvey.

The panel had a curious history. It was commissioned in the early 1950s for the MHS, and Clarke executed the frieze on-site, using modern tools (electric drills) as well as more traditional ones (hammer and chisel). When it was completed in 1956, however, its size—thirteen feet long and four feet high—exceeded the display space, and so the MHS lent it to the University of Montana in Missoula. There it hung in the campus field house for the next three decades, presiding over boxing matches, college basketball games, and even a concert by the Grateful Dead, before finding a second home in Great Falls at the Montana School for the Deaf and Blind. Seven years later the MHS reclaimed the panel as the centerpiece for the planned retrospective. Ever since, it has welcomed visitors from its perch just inside the building’s entrance.

2

The peregrinations of

Blackfeet Encampment

stand in marked contrast to the permanence of its creator. Except for short stints at several boarding schools during his childhood and adolescence, John Clarke spent virtually his entire life on the Blackfeet Reservation and its immediate environs. Even as his artworks impressed American and European audiences and found homes in the personal collections of President Warren G. Harding and John D. Rockefeller Jr., Clarke himself remained rooted firmly in place.

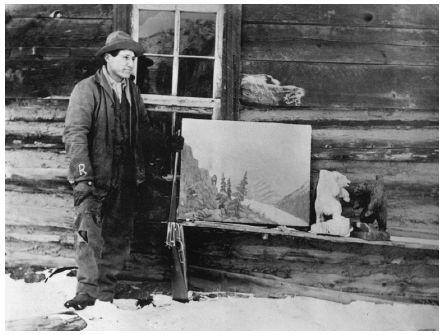

There were, of course, compelling reasons for him to stay put. For one thing, his deafness, coupled with his sustained poverty, imposed significant limitations. For another, he was deeply attached to the environment of northern Montana, which inspired his artistry and furnished unparalleled opportunities for outdoor recreation. Indeed, one photo from his youth neatly captures these twin passions: Clarke, rifle in hand, posing proudly outside a log cabin in the dead of winter, with a landscape painting and two carved bears resting on a ledge nearby.

There was likely another reason behind Clarke’s persistence in East Glacier Park, however. It had become harder for peoples of mixed ancestry to negotiate life beyond the reservation boundaries. What had been a permeable membrane for his aunt Helen, one through which she passed often if not always easily, had thickened as the twentieth century wore on. The gulf between the races was perhaps most obvious at the edges of the Blackfeet Reservation, in places like Cut Bank, the nearly all-white town on the eastern side whose residents and shopkeepers looked upon Indian visitors with withering hostility. In time the difference between full and mixed-blood peoples held meaning primarily on the reservation itself; to whites living nearby, anyone with obvious native ancestry was simply “Indian.”

3

In truth, such distinctions based on degree of blood seem to have meant little to John Clarke, who considered himself a Piegan. This is not to say that he denied his Anglo ancestry or showed antipathy toward whites; quite the contrary—he married a white woman, with whom he adopted a white daughter. And he had numerous white benefactors, patrons, and friends. Nevertheless, his life and career suggest that, in the end, he identified more with Coth-co-co-na’s people than with Malcolm Clarke’s, and thus chose to walk primarily in one world, not two.

John L. Clarke, ca. 1910s. This photo captures Clarke’s twin passions: hunting and art. The one pursuit informed the other, as his adventures in Glacier country allowed him to observe closely the wildlife he later rendered in cottonwood. Courtesy of Joyce Clarke Turvey.

A World of Muffled Sound

Until the twentieth-century advent of antibiotics like penicillin, scarlet fever was a childhood scourge. Parents of afflicted youngsters had little warning of the horrors about to ensue—perhaps a complaint of slight malaise or a passing chill. Yet when the disease took hold, terrifying symptoms appeared in rapid succession: convulsive vomiting, powerful spasms, and then a fever rising to 105 degrees or beyond. Usually by the second day, victims bore the telltale rash (the result of toxin released by the bacteria), a constellation of red dots emanating from the neck and chest and spreading eventually over the patient’s entire body.

Though not as lethal as smallpox, scarlet fever still exacted its own grim toll. In the late nineteenth century the Boston City Hospital reported a mortality rate of nearly 10 percent for patients afflicted with the disease, and a rate two to three times higher during especially severe outbreaks. Though adults were also susceptible, children, particularly those under the age of six, were the principal victims. In the absence of any known treatment, anguished parents could do little except alleviate the discomfort and pray for recovery, which could take weeks.

4

Horace Clarke and his wife, Margaret, called First Kill by the Piegans, of whom she was a full-blooded member, knew intimately the terrors of scarlet fever. During the 1880s the sickness passed through their modest ranch in Highwood, Montana, like the angel of death. Though it spared their children Malcolm, Ned, and Maggie, it carried off four other boys all under the age of five. And it ravaged another, John, destroying his ability to hear.

5

The malady seized John in the autumn of 1883, when he was two and half years old. The timing was typical of the disease, which tended to strike in spring and fall, as were its side effects. A leading medical sourcebook from the time identified scarlet fever as a chief cause of deafness in children, owing to the spread of inflammation from the throat to the middle ear, which in acute cases led to permanent hearing loss. Though it could not have seemed so at the time, John was actually among the fortunate, for he escaped other dire complications such as kidney failure and meningitis.

6

Margaret must have played some role in her son’s care, which probably involved swabbing his feverish body with a wet cloth and moisturizing his skin as it began to slough off after the rash subsided, but she would have been limited by her pregnancy with Maggie, who was born on Christmas Eve 1883. Thus, responsibility for John probably fell to Horace’s mother, Coth-co-co-na, and especially to Horace’s sister Isabel, who had recently returned from her aunt Charlotte’s Minneapolis home, where she had spent the decade after their father’s murder. The siblings were close; in fact, knowing Isabel’s love of music, Horace sometime around 1880 arranged for the shipment of a piano upriver from St. Louis.

7

How the family initially reacted to John’s impairment is unknown, but for the little boy with black hair and dark complexion, it must have been frightening to be suddenly unable to hear the timbre of his parents’ voices or the gentle lowing of the family cattle. Moreover, John’s deafness sharply ended his acquisition of speech at just the moment that many children experience rapid linguistic development. Supposedly, he was capable of only one sound—an alarmed yell—and as a child he was prone to violent tantrums when he could not make himself understood.

8

Still, he could see with perfect clarity as adults conversed around him, as his aunt Isabel delighted visitors with her piano playing and, most poignantly, as his older brothers left with their aunt Helen for the Carlisle School in Pennsylvania.

John, by contrast, had no access to proper education until he was a teenager, because the closest Indian school at Fort Shaw, on the other side of Great Falls, made no accommodation for students with disabilities.

9

Presumably, he spent the majority of his time at Horace’s side, tending the Clarke livestock and, after the family moved to Midvale around 1889, accompanying his father on hunting and fishing trips into the wilds that later became Glacier National Park. Such excursions stimulated his other senses—the smell of pine, the taste of wild berries, the sting of glacier-fed streams. But the sight of fauna left the deepest impression upon John: playful grizzly bears and sleek mountain lions, proud bighorn sheep and sure-footed mountain goats.

This idyll, if that it was, came to an abrupt conclusion in the fall of 1894 when John left for the bleak hamlet of Devil’s Lake, some seven hundred miles distant, to attend the North Dakota School for the Deaf. Why his parents chose that institution is uncertain, especially since Montana had established its own such facility just south of Helena the year before. Perhaps it was the NDSD’s strong academic reputation and its visionary superintendent that swayed them, or the handsome new schoolhouse made of brick and featuring amenities like wood-burning stoves and oil lamps. By contrast, the fledging Montana school operated in a leased two-story house.

If the choice of North Dakota was unusual, the timing was probably not, for John’s world began unraveling in the early 1890s, starting with the breakup of his parents’ marriage. After some fifteen years together, Horace and Margaret “quit each other,” in the parlance of the day. While in times past John might have turned to his aunts for comfort, they were largely unavailable as this family crisis unfolded: Helen was working in Indian Territory, and in 1891 Isabel had married Tom Dawson, the mixed-blood son of a prominent American Fur Company trader. His grandmother Coth-co-co-na was in failing health and died the following summer, leaving John effectively alone, at age thirteen, to confront the dissolution of his home life. Little wonder, then, that his parents chose that moment to ship him off to school.

F

ORMAL INSTRUCTION FOR

the deaf in the United States began in 1817 with the establishment of the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, the first permanent institution of its kind in the nation.

10

By the end of the nineteenth century such institutions could be found across the country, although rural areas remained chronically underserved, a problem that preoccupied Anson Rudolph Spear, a twenty-nine-year-old deaf Minnesotan. Spear had studied briefly at Gallaudet College, founded in 1864 in Washington, D.C., and later worked at the Census Bureau before returning home to the Twin Cities in the early 1880s. In particular, he worried that deaf children in the new state of North Dakota—admitted to the union in 1889 and bordering Minnesota immediately to the west—would suffer from limited learning opportunities.

During North Dakota’s inaugural legislative session, Spear became a fixture in the halls of the state capital at Bismarck, lobbying members of the house and the senate to remember the most disadvantaged of their constituents. His efforts paid off when on the very last day of the session the legislature overrode the veto of the state’s parsimonious governor and endorsed a bill providing for the creation of the NDSD. Housed originally in a vacant bank building, the school opened its doors in the fall of 1890, welcoming twenty-three students. Spear became the first superintendent, thought to be the youngest leader of a state-run educational institution anywhere in the country.

11