The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History (32 page)

Read The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History Online

Authors: J Smith

It was on February 6, 1981, that the prisoners returned to coordinated action, initiating their eighth collective hunger strike, demanding association, the release of Günter Sonnenberg, and that their prison conditions be monitored by the International Commission for the Protection of Prisoners and Against Isolation Torture, which had been set up for this purpose in 1979.

The prisoners had hoped that Stefan Wisniewski would use the occasion of his trial, which began in September 1980, to announce their strike in his opening statement. But this was to be the first trial directly related to the Schleyer kidnapping, and Wisniewski felt it should be used to discuss the events of â77. By calling the hunger strike at this time, public attention would be shifted to the prisoners' struggle. This was a source of some discord and led to Wisniewski quietly distancing himself from his comrades, while publicly maintaining solidarity with them. As he would explain years later, “Having posed the question of the prisonersâour weakest pointâas politically central in 1977, there was no way I wanted to repeat this fatal error as a prisoner myself.” Nonetheless, once the strike began he did refuse food for six weeks and encouraged various social prisoners to do the same.

5

Hundreds of prisoners joined the strike, most of them not from the RAF. As militants in one city explained, “Only with the hunger strike of about 300 political prisoners a connection among us in Hamburg was established again that made it possible for the different groups to enter into a political discussionâ¦. Solidarity with the political prisoners

and the fight against imperialism also became part of the politics of the squatters movement in Berlin and the antinuclear movement in northern Germany.”

6

In West Berlin, thousands of people marched in support of the prisoners, the largest demonstration of its kind in years.

7

On March 4, members of the FRG Relatives Committeeâincluding the mothers of Rollnik, Stürmer, and Wagner, as well as Becker's sisterâoccupied the offices of

Spiegel

magazine, in an attempt to force the media to begin reporting on the strike.

8

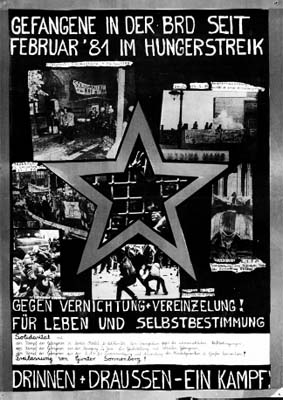

“Prisoners in the FRG on hunger strike since February â81; Against extermination and isolation! For life and self-determination; Freedom for Günter Sonnenberg; Inside and outsideâone struggle!”

On March 8, International Women's Day, a relatively new group called Women Against Imperialist War marched on Lübeck prison in an attempt to bridge the gap that had always separated the women's movement from the RAF.

9

There was an important victory on March 11, when Gabriele Kröcher-Tiedemann, Christian Möller, and Rolf Clemens Wagnerâwho were all being held in Switzerlandâannounced that their demands had been partially met. They had been promised that their conditions would be relaxed immediately, and that they would be integrated into the general population in the near future.

10

The three resumed eating, issuing a statement in which they explained that, “We view these developments as further proof that it would also be possible for the authorities in the FRG to take

concrete steps

to address the demands put forward by the comrades from the guerilla⦠thereby allowing them to call off their hunger strike.”

11

Sympathy for the prisoners was not confined to partisans of armed struggle; once again, sections of the liberal intelligentsia were successfully mobilized, with some progressive doctors and clergy taking a public stand.

12

Two days after the victory in Switzerland, Amnesty International weighed in, urging the West German authorities to abolish solitary confinement and small-group isolation as regular forms of imprisonment.

13

When a female justice official showed up to speak at a women's conference in Hamburg she was ejected, denounced by WAIW as “being one of the authorities we wanted to attack but not talk to.”

14

This same conference passed a resolution supporting the prisoners' demands and requesting that the International Federation of Women and the World Council for Peace do the same. Also in Hamburg, a demonstration of three hundred women marched on the offices of the NDR public broadcaster to break through the news blackout surrounding the strike.

15

Even minor, nonviolent, actions could have serious consequences. For instance, Sybille Haag and several other supporters would spend weeks in jail for hanging a banner from an overpass on the autobahn between Stuttgart and Heilbrunn.

16

In another case, a young woman spent six weeks in remand for helping to organize a demonstration in support of the prisoners. Ten people caught spraypainting slogans on highway signs similarly spent six weeks in remand, while one graffiti artist who had been apprehended writing “War to the Palaces” on a fence received a one-year prison sentence. In all of these cases the relatively minor offenses relating to vandalism were supplemented by prosecution for supporting a “terrorist” organization under §129a, and those thus charged found themselves subject to the same treatment as captured combatants: lawyers' visits through glass partitions, censored mail, restricted visitors, exclusion from group activities, solitary yard time, etc.

17

Such cases were not rare, nor was the state's reaction considered out of the ordinary. The RAF would later note that fifty people had been charged under §129a during the strike,

18

but this was just the tip of the iceberg: the Attorney General had launched 133 preliminary investigations for promoting a terrorist organization, and in the first half of the year, there were 263 proceedings against 600 people: all for nonviolent support activitiesâleaflets, posters, slogans, and bannersâduring the hunger strike.

19

Once again, Amnesty International was successfully lobbied to protest this repression. As the international human rights organization would explain in its annual report:

[I]n Amnesty International's opinion the arguments in indictments and judicial decisions against supporters of the hunger-strike constitute a threat to the nonviolent exercise of the freedom of expression. Judge Kuhn,

20

a judge at the Bundesgerichtshof (federal court), who is responsible for the pre-trial proceedings in virtually all these cases, has argued in many cases that the “ultimate aim” of the hunger-strike was the continued existence of the

Red Army Fraction. Supporters of the hunger-strike who he felt “knew and wanted” this “ultimate aim” therefore supported the terrorist organization, even though the opinions they expressed related only to the direct demands of the hunger-strikers. Many supporters of the hunger-strike were consequently held in investigative detention charged with “making propaganda for a terrorist association” (Article 129a of the criminal code) because of “ultimate aims” which Judge Kuhn held to be apparent from, for example, the use of a red five-pointed star.

21

While nonviolent protesters were facing such repression, there were also other forms of support that could be termed “more active behavior”: the SPD

Land

office in West Berlin was firebombed, as was the American International School in Düsseldorf-Lohausen, a bomb went off outside a U.S. intelligence building in GieÃen doing 200,000

DM

in damages, and in Frankfurt nine U.S. military police vehicles were torched at the Gibbs Barracks and a U.S. Army employment office was firebombed.

22

In that same city, in what might have been an homage of sorts, two department stores were set alight,

23

and on April 10, attempts were made to torch two more military installations. Then on April 12, a Bremen to Hannover military transport train was derailed using steel cables, causing approximately 200,000

DM

in damages.

24

While these attacks were welcomed, the RAF prisoners were not happy with every action supposedly carried out on their behalf: in Cologne, a bomb was set off in the subway, injuring one transit worker and six cops, and a train was derailed by metal chains laid across the tracks. The prisoners condemned these attacks, insisting that they must have been the work of state agents attempting to discredit the hunger strike.

25

As in previous strikes, participants faced the ordeal of force-feeding and increased brutality from their jailers. For instance, Angelika Speitel, who had suffered from depression since her 1978 arrest, and had attempted suicide in 1980, was repeatedly taken to the hole, stripped naked by male guards, put in chains, and denied water. All throughout, she remained under constant observation.

26

In Celle's high-security wing, Karl-Heinz Dellwo and resistance prisoner Heinz Herlitz were force-fed by means of a tube inserted through the nose.

Die Zeit

reported that it was such a bad procedure that in the end even the prison doctor no longer wanted to continue doing it.

27

Such force-feeding was little more than torture, as the procedure was excruciatingly painful, and yet the amount of nutrition delivered was negligible.

By early April, seven prisoners were in serious condition;

28

once again Amnesty International contacted officials, noting the risks the prisoners were enduring, and urgently called upon authorities to meet the demand to abolish isolation.

29

Yet despite the growing support from both liberal and militant quarters, the state held firm.

Demonstrators call for association and support for the hunger strike.

Tragically, on April 15, what everyone feared, occurred: after sixty-four days without food, Sigurd Debus joined Holger Meins as the

second prisoner to die during a RAF prisoners' hunger strike. A tall man, measuring six feet four, he weighed 119 pounds at the time of his death. He had been refusing food since February, and had been subjected to force-feeding beginning on March 20.

Dr. Görlach of the prison office was responsible for Debus at the Hamburg remand center, where he and other hunger strikers had been brought. There he worked under the close supervision of Dr. Friedland, who had been outspoken in his view that hunger strikes must be dealt with forcefully, as an expression of the guerilla's war against the constitutional state.

30

Debus's health had taken a rapid turn for the worse in the first week of April; his mother was permitted to visit with him, but he didn't recognize her, and doctors declared that he may have suffered brain damage.

31

He lost consciousness on April 7, spending eight days in a coma before he died.

The doctors conducting Debus's autopsy found that “the immediate cause of death was the death of brain tissue as a result of cerebral bleeding and a significant increase in pressure on the brain.”

32

It was unclear whether this was caused by a stroke or as a result of the insufficient nourishment he received during force-feeding. Critics were quick to blame this cerebral hemorrhage on the fact that Görlach had started adding fat emulsion to the fluid Debus was being force-fed.