The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History (33 page)

Read The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History Online

Authors: J Smith

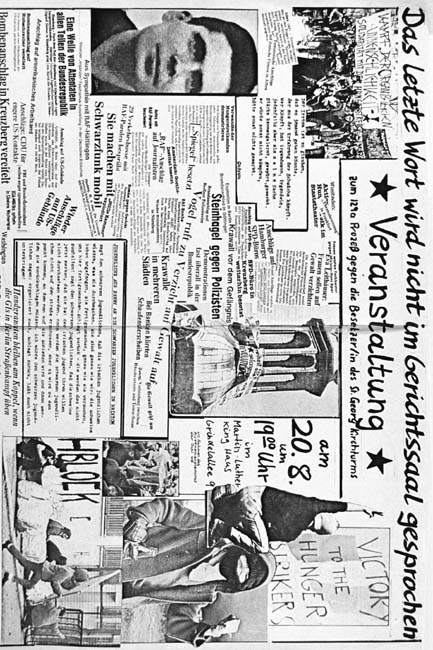

Funeral procession for Sigurd Debus.

Just hours after Debus's death, in a public statement ostensibly addressed to Amnesty International, Federal Justice Minister Jürgen Schmude announced that while recognizing prisoner of war status and granting association in one large group were both out of the question, the

Länder

Justice Ministers would meet to discuss some improvements in prison conditions.

33

The RAF prisoners were led to understand that they would no longer be held in individual isolation, and that more groups would be established. According to some supporters, the timing was no coincidenceâthe state had been waiting for someone to die before making any concessions:

Sigurd's death was planned. It was carefully planned that he should die because thereby [the] most could be made out of his death in the media. Sigurd was not a member of the RAF, but he joined the hungerstrike, not, as the authorities would have the public believe, out of solidarity, but because the demands of the RAF prisoners were also his own. He wanted to be put together with prisoners of the RAF as those were his comrades and he was determined not to bear any longer the situation in the so-called “reform prison” he was in, where he could not develop and communicate with anyone of his own history and identity. So it was not just an act of solidarity but an act of political consciousness and self-determination that made him join the hungerstrike. The authorities let his murder coincide with the ending of the hungerstrike to show the public that the RAF is willing and able to sacrifice the life of someone who was not even a member of their own group for their unreasonable demands, to show that the RAF is determined to “step over corpses.”

34

Debus died on the Thursday before the long Easter weekendâoften an occasion for political protest in the FRGâand that evening people came together in spontaneous demonstrations in several cities. As detailed in one movement history of the West Berlin squatting scene:

In Kreuzberg a loudspeaker van toured the streets announcing the news. The reaction was swift and once again caught the police off guard. A thousand people made their way immediately to the Kurfürstendamm and, rushing through the Easter tourist crowds, smashed 80% of the windows⦠When the police arrived in force a half an hour later most of the damage was already done and there was nobody around to arrest. From then on the troop

carriers and the paramilitary uniforms of the riot police became part of the sights of the city centre. It was becoming blatantly obvious that a large and militant minority had rejected the West German state and the consumer society.

35

The following days witnessed dozens of bomb threats across the country, accompanied by dozens of actual firebomb attacks on government buildings. The Saarbrücken offices of the Ministry of the Interior were hit, as was the Lübeck Employment Office, and the Psychology Institute at Hamburg University.

36

The Max Planck Institute's West Berlin offices were also bombed, a communiqué explaining that the institute was being targeted for its research into torture,

37

and antinuclear activists blew up a power mast at a nuclear power plant near Bremen, drawing a clear connection to the hunger strike in their communiqué.

38

At the same time, over a thousand people marched in Hamburg with banners that read “We Mourn Sigurd Debus,”

39

and various SPD offices were firebombed in the port city.

40

Spiegel

magazine asked, “Who were those hundreds of masked people who wrecked cars, smashed windows, hoisted banners, and occupied churches across the land?” Journalists wrote ominously about the resistance in the streets, referring to “black blocs” and

Chaoten.

The BKA described the weekend's events as a “people's storm of solidarity.”

41

Although the high-security wings remained, the wall of political isolation that the state had erected around the prisoners had been breached.

Sigurd Debus had never been a member of the RAF but had gravitated toward armed struggle after leaving the KPD/ML in the early seventies. He helped to bring together a small group which made contact with the RAF, but opted to remain separate, preferring to act on their own. In 1973 they bombed the Cologne Federal Association of German Industrialists building and planted a bomb (which failed to detonate) at a Hamburg municipal government office. Then on February 28, 1974, Debus was captured in Hamburg along with Karl-Heinz Ludwig and Wolfgang Stahl when a bystander blocked their escape following a bank robbery. (A fourth comrade, Gert Wieland, was arrested soon after.)

Debus conducted a political trial, praising the recent Lorenz kidnapping, and when the RAF's Holger Meins Commando seized the West German embassy in Stockholm on April 24, 1975, he and Stahl were among those whose freedom was being demanded. The Stockholm action failed, and his trial statements were deemed to constitute aggravating circumstancesâone month later Debus received a twelve-year sentence for the two bombings and three counts of robbery. He spent the next three years in strict isolation, subjected to daily cell and strip searches before and after his solitary yard time.

1

When Debus was finally transferred out of isolation, it was as part of an ambitious police gambit to infiltrate the RAF. At the prompting of the secret police, the Celle prison warden

had him transferred next to two social prisonersâKlaus Dieter Loudil and Manfred Bergerâwho had been secretly recruited by the

Verfassungsschutz.

Pretending to befriend Debus, Loudil and Berger began discussing the possibility of escape, and also helped “smuggle” messages and a radio in for him. In September 1977, Berger was released, and then in May 1978 Loudil pretended to escape from a work furloughâin actual fact, he had been secretly pardoned by Holger Börner, the Hessian president.

2

On July 25, 1978, with the help of the GSG-9, the

Verfassungsschutz

detonated a bomb outside Celle, hoping to breach the prison wall. The idea was that Debus would escape and meet up with Loudil and Berger, leading them into the underground, and hopefully to the RAF. Comrades in Amsterdam had already been approached by undercover Dutch agents, and asked if they would be able to provide Debus with shelter, as an escape plan was in the works.

3

A multinational penetration of the underground was what was intended.

The plan failed due to a technical error: the

Verfassungsschutz

agents' bomb was too weak to break through the prison wall, and Debus never escaped. Instead, this “attempted breakout” was used as justification to send him back to isolation, and for the Hannover police authority to float the story that the RAF's “Holger Meins Commando” had attempted the breakout.

4

(That all members of the actual Holger Meins Commando had been killed or captured in 1975 seemed not to bother anyone.) The entire plot was only exposed years later, in 1986, as part of a parliamentary inquiry into the activities of secret agent Werner Mauss.

Over the next years, Debus's conditions would be slowly relaxed, and in February 1980 he was transferred into general population at Fuhlsbüttel. According to

konkret

magazine, Debus joined the â81 hunger strike because he felt that with the liberal Gerhart Baum as minister of the interior, there was a chance to improve prison conditions for everybody, and because he personally hoped to win association with other political prisoners.

_____________

1

Juhnke “Tod durch Ernährung.”

2

Hinrich Lührssen, “âFeuerzauber' mit dunklen Figuren,”

Die Zeit,

June 12, 1988.

3

de Graaf (2009), 34.

4

Hans Schueler, “Feuerzauber am Allerufer,”

Die Zeit,

May 2, 1986.

Change has never come from the elderlyâ¦. It's a question of mobility and power, because no stiffness, impairment, or fatigue has begun to set in yet. When you're younger, you have a lot more energy. One just has to accept that. But you cannot expect them to continue all the same things or to be just like you.

Irmgard Möller

42

Throughout the FRG, the prisoners emerged as an important, but complicated, reference point for the new generation of rebels.

As we have seen, the

Autonomen

had developed out of the antinuclear struggles of the previous decade, establishing their wider perspective in the antimilitary resistance in Bremen in May 1980. Since then, material conditions, exacerbated as youth unemployment hit a postwar high, had provided a promising new theatre of struggle: the squatters' movement.

For years, landlords had allowed buildings to fall into disrepair and go empty in what has been referred to as an “informal capital strike” against rent controls that had been passed in the mid-1970s. Once these properties became run down, their owners became eligible for low-interest city loans to build condominiums for the upwardly mobile. The result was tens of thousands of people without affordable housing, while thousands of houses and apartments, oftentimes entire city blocks, stood empty.

43

Things were especially bad in West Berlin, where the political mood was aggravated by the news that members of the Senate had broken their own rules to make 160 million

DM

in loans to Dietrich Garski, a well-connected architect, who had invested the money in bankrupt housing projects abroad.

Immigrant “guest workers” from Italy and Turkey had pioneered the first housing occupations at the start of the 1970s, but within a few years the

Spontis

and members of the guerilla support scene had come to dominate the growing number of overtly political squats.

44

This provided a history that the

Autonomen

could identify with, and they soon renewed a tradition that combined practical concerns with a vision of a better society to come. Like the antinuclear occupations, the squats

pushed people to become more radical, both by virtue of the fact that they were deciding to live collectively in new ways, and also by the illegal nature of the exercise itself.

On December 12, 1980, police confronted some people trying to occupy a house in the Kreuzberg area of West Berlin, a neighborhood that had become a stronghold for the alternative movement and the center of the city's squatter scene. News of the showdown quickly spread, sparking rumors that a house had been cleared and that a second eviction was imminent; barricades went up and hundreds of people spent hours fighting with cops and looting nearby stores. Over one hundred were arrested, and over twice that many injured, in what became known as the 12-12 riot.

45

As a local social worker explained to the

New York Times: