The Reenchantment of the World (19 page)

Read The Reenchantment of the World Online

Authors: Morris Berman

Plate 12. Isaac Newton, 1689. Portrait by Godfrey Kneller. Lord Portsmouth

and the Trustees of the Portsmouth Estate.

Plate 13. Isaac Newton, 1702. Portrait by Godfrey Kneller. Courtesy,

National Portrait Gallery, London.

Plate 14. Isaac Newton, ca. 1710. Portrait by James Thornhill.

By permission of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Plate 15. Isaac Newton, 1726, the year before his death. Mezzotint by

John Faber, after painting by John Vanderbank. Courtesy, Prints Division,

The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

classes were suppressed at the level of work and labor, so did the middle

and upper classes keep themselves in check at the level of literary

and intellectual activity. The attack on enthusiasm was breathtakingly

successful, and is reflected in the poetry of the eighteenth century (the

carefully contrived couplets of Dryden and Pope) as well as the notion

of classical scholarship itselt. "The classics!" cried Blake. "It is the

classics, and not Goths nor monks, that desolate Europe with wars."26

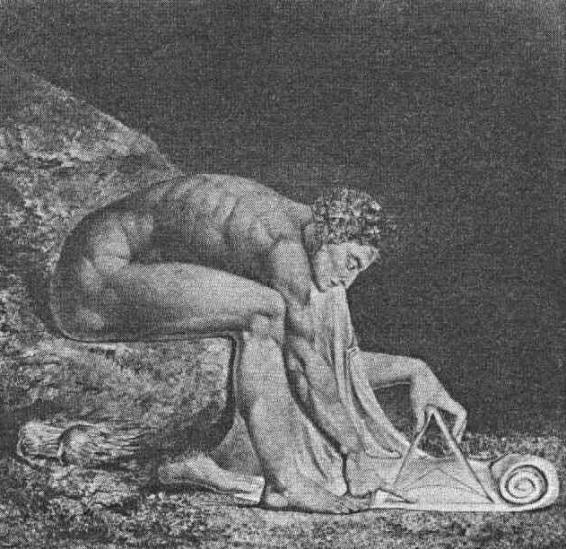

In his painting of Newton, carving up the world with a compass (Plate

16), Blake tried to show the blindness of this orientation to nature;

and nowhere did he say it better than in his verse letter to Thomas Butts

(1802):

Now I a fourfold vision see,

And a fourfold vision is given to me;

'Tis fourfold in my supreme delight

And threefold in soft Beulah's night

And twofold always. May God us keep

From Single vision & Newton's sleep! 27

Plate 16. William Blake, Newton (1795). The Tate Gallery, London.Newton is pictured in Blake's painting sitting at the bottom of the

Sea of Space and Time. The polyp near his left foot symbolizes, in

Blake's mythology, "the cancer of state religion and power politics,"

while Newton stares at his diagram "with the catatonic fixity of 'single

vision'. . . ." 28

Blake's attack on the Newtonian world view raises a question that Hill

has made the theme of

The World Turned Upside Down

: how can we be

so sure that the way things are is right side up? Bourgeois society,

he notes, was a powerful civilization, producing great intellects in

the Newtonian and Lockean mold, But, he adds, it was

the world in which poets went mad, in which Locke was afraid of

music and poetry, and Newton had secret, irrational thoughts which

he dared not publish. . . .

Blake may have been right to see Locke and Newton as symbols of

repression. Sir Isaac's twisted, buttoned-up personality may help us

to grasp what was wrong with the society which deified him. . . . This

society, which on the surface appeared so rational, so relaxed,

might perhaps have been healthier if it had not been so tidy, if it

had not pushed all its contradictions underground: out of sight,

out of conscious mind. . . . What went on underground we can only

guess. A few poets had romantic ideas out of tune with their world;

but no one needed to take them too seriously. Self-censored meant

self-verifying.29

"Great though the achievements of the mechanical philosophy were," Hill

writes at another point, "a dialectical element in scientific thinking,

a recognition of the 'irrational' (in the sense of the mechanically

inexplicable) was lost when it triumphed, and is having to be painfully

recovered in our own century."30

The emphasis here is on the word "painfully." In Chapter 3, I discussed

the role of surrealist art in attempting to liberate the unconscious. But

because the unconscious is so repressed, its great mouthpiece in postwar

Europe and America has become not art, but madness. Without going into

too much detail, it is necessary to point out that a major part of the

psychotic experience is the return to the perception of the world in

Hermetic terms. That madness is the best route to this perception I tend

to doubt; but the fact that madness triggers the premodern epistemology

of resemblance does suggest that the insane are onto something we have

forgotten, and that (cf. Nietzsche, Laing, Novalis, Hölderlin, Reich

. . .) our sanity is nothing but a collective madness.

Although it would take extensive clinical studies of insanity to establish

this argument, even a casual review of the case histories described by

Laing in "The Divided Self" tends to substantiate it.31 In general, says

Laing, having a disembodied self creates a sense of merger or confusion

at the interface between inside and outside. As in soteriological

alchemy or mystical experience, the subject/object distinction blurs;

the body is not felt as being separate from other things or people. One

of Laing's patients, for example, did not distinguish between rain on her

cheek and tears. She also worried that she was destructive, in the sense

that if she touched anything, she would literally damage it (antipathy

theory). Schizophrenics occasionally demonstrate a belief that inanimate

objects contain extraordinary powers, and Laing describes the case of

a man who, while on a picnic, undressed and walked into a nearby river,

declaring that he had never loved his wife and children, pouring water

on himself repeatedly, and refusing to leave the river until he had been

"cleansed." Here we have the original notion of baptism, the belief that

water bears the impressed virtue of God (doctrine of signatures), and

thus has healing powers. Another patient practiced various techniques

to "recapture reality," such as repeating phrases she regarded as real

over and over in the hope that their "realness" would rub off on her

(sympathy theory, notion of 'mana'). Finally, as I indicated in Chapter

3, Laing's own method is alchemical in that it follows the notion of

participating consciousness, or sympathy theory. All humanistic therapies,

in fact, are rooted in original participation. The use of art, dance,

psychodrama, meditation, body work, and the like ultimately boils down

to a merger of subject and object, a return to poetic imagination or

sensuous identification with the environment, In the last analysis, the

good therapist is nothing more than the master alchemist to his or her

patients, and effective therapy is essentially a return to the inherent,

organic order that magic represented. The classification schemes of modern

science, their Linnaean order and precision, purport to arise from the

ego alone, to be fully rational-empirical. They thus represent a logical

order that is imposed on nature and the human psyche. As a result, they

violate something that magic, for all its technological limitations,

had the instinctive wisdom to preserve.

Madness is, in the end, a statement about logical categories, and its

reversion to the structure of premodern thought represents a revolt

against the reality principle that it sees as crushing the human

spirit. The increasing incidence of madness in our time reflects the

desperate need for the recovery of dialectical reason. Does alchemy, or

technology, represent the altered state of consciousness? Is material

production, or human self-realization, most consonant with true,

human needs? Is subjugation of the earth, or harmony with it, the best

way to proceed? I would submit that there is only one answer to these

questions, and only one conclusion to our survey of the disenchantment

of the world: in the seventeenth century, we threw out the baby with the

bathwater. We discounted a whole landscape of inner reality because it

did not fit in with the program of industrial or mercantile exploitation

and the directives of organized religion. Today, the spiritual vacuum

that results from our loss of dialectical reason is being filled by all

kinds of dubious mystical and occult movements, a dangerous trend that

has actually been encouraged by the ideal of the disembodied intellect

and the classical scholarship that Blake rightly found revolting. Modern

science and technology are based not only on a hostile attitude toward

the environment, but on the repression of the body and the unconscious;

and unless these can be recovered, unless participating consciousness

can be restored in a way that is scientifically (or at least rationally)

credible and not merely a relapse into naive animism, then what it means

to be a human being will forever be lost.

The remainder of this book will be devoted to an exploration of such

options.

5

Prolegomena to

Any Future Metaphysics (1)

Perhaps we need to be much more radical in the explanatory hypotheses

considered than we have allowed ourselves to be heretofore. Possibly

the world of external facts is much more fertile and plastic than we

have ventured to suppose; it may be that all these cosmologies and

many more analyses and classifications are genuine ways of arranging

what nature offers to our understanding, and that the main condition

determining our selection between them is something in us rather

than something in the external world.

--E. A. Burtt, "The Metaphysical Foundations

of Modern Science"

In previous chapters we have discussed the modern scientific outlook,

demonstrated its relationship to certain social and economic developments,

and examined the psychological landscape that it destroyed. This

analysis suggests that the Western world paid a high price for the

triumphs of the Cartesian paradigm and that there are severe limits to

it in terms of human desirability. Indeed, even its objective accuracy

can be debated for, as we have seen, its triumph over the metaphysics

of participating consciousness was not a scientific but a political

process; participating consciousness was rejected, not refuted. As a

result, we are forced to consider the possibility that modern science

may not be epistemologically superior to the occult world view, and that

a metaphysics of participation may actually be more accurate than the

metaphysics of Cartesianism. A number of scientific thinkers, including

Alfred North Whitehead, have argued this thesis in one form or another

and, as early as 1923, the psychologist Sándor Ferenczi called for the

"re-establishment of an animism no longer anthropomorphic."2 Yet our

culture hangs on to mechanism, and to all of the problems and errors it

involves, because there is no returning to Hermeticism and -- apparently

-- no going on to something else.

I have promised to devote the second half of this book to "something else,"

and in subsequent chapters I shall enlarge on what might serve as a

post-Cartesian world view. Before contemplating an alternative, however, it

is necessary to elaborate on a key weakness in the epistemology of modern

science -- the fact that it contains participating consciousness even

while denying it. It is this denial that has created the characteristic

paradoxes of scientific thought, notably its radical relativism, and which

has also made it impossible for orthodox scientific thinking to evolve in

new directions, such as those suggested by quantum mechanics. I maintain

that an understanding of the stubborn persistence of participating

consciousness can help us to solve the problem of radical relativism

and also suggest some theoretical underpinnings for a post-Cartesian

science. The arguments I am going to advance, then, are as follows:

(1) Although the denial of participation lies at the heart of modern

science, the Cartesian paradigm as followed in actual practice is riddied

with participating consciousness.

(2) The deliberate inclusion of participation in our present epistemology

would create a new epistemology, the outlines of which are just now

becoming visible.

(3) The problem of radical relativism disappears once participation is

acknowledged as a component of all perception, cognition, and knowledge

of the world.

Fortunately for this discussion, point (1) is the central focus of two

recent and brilliant critiques of modern science: Michael Polanyi's

"Personal Knowledge," and Owen Barfield's "Saving the Appearances."3

Polanyi's major thesis is that in attributing truth to any methodology we

make a nonrational commitment; in effect, we perform an act of faith. He

demonstrates that the coherence possessed by any thought system is not

a criterion of truth, but "only a criterion of

stability

. It may

[he continues] equally stabilize an erroneous or a true view of the

universe. The attribution of truth to any particular stable alternative

is a fiduciary act which cannot be analysed in non-commital terms."4 The

faith involved, according to Polanyi, arises from a network of unconscious

bits of information taken in from the environment which form the basis

of what he calls "tacit knowing." What exactly does this concept mean?

We already have alluded to the notion of a gestalt perception of reality,

of finding in nature what you seek. Philosopher Norwood Russell Hanson

used the illustrations given in Figures 10 and 11 to make this point:5

Other books

Mystic and Rider (Twelve Houses) by Shinn, Sharon

The Granville Sisters by Una-Mary Parker

The Boleyn King by Laura Andersen

Medea's Curse by Anne Buist

Pushin' by L. Divine

The Silver Casket by Chris Mould

Prerequisites for Sleep by Jennifer L. Stone

Maybe Baby by Andrea Smith

Silencio sepulcral by Arnaldur Indridason

Timeless Mist by Terisa Wilcox