The Ride of My Life (3 page)

When Travis and I were younger, my dad didn’t let us join any teams until we were in the sixth and seventh grade. He thought wrestling would teach us discipline, so he signed both of us up at the local YMCA.

His favorite story is from a meet in El Reno, Oklahoma. He told me the correct way to have good sportsmanship was to pray for my opponent before the match. According to my dad, I looked at him and said, “Dad, could I pray for him after the match?”

When I was twelve, I came home after basketball practice and our house was in flames. There was an electrical short in the stove, and the kitchen caught on fire. The whole structure went up fast. My brother Travis was in the shower and escaped with nothing but a towel. My mom and I pulled into the driveway just as the dog ran out of the house, fur on fire. The rescue squad aimed their high-pressure water hose at the dog to put him out, and it blew him in two. This was on a Saturday. Our homeowners’ insurance policy had run out on Friday, and the new policy didn’t take effect until Monday morning. Nearly all of our possessions were gone. The only thing I had was the basketball uniform I was wearing at the time. My mom, who was crazy about photos, lost almost all the family photo albums, negatives, everything.

We moved into a trailer with my cousins until we bought another house. The new place was by a creek, which flooded twice, wrecking the ground floor of the house each time, taking any remaining family photos and mementos we had with it. Having everything and then practically nothing was rough, but we stuck together as a family.

I learned that even the nicest material things in life are temporary.

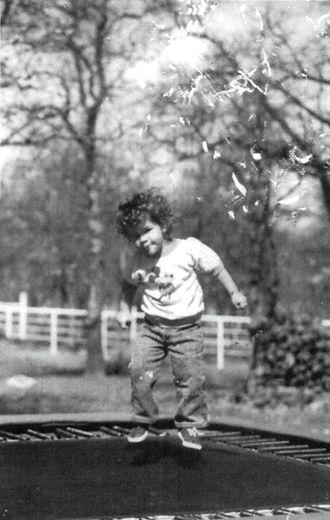

I grew up bouncing on trampolines. I loved gravity before I even knew what it was, and experimenting with ways I could play with it. I’m two years old in this shot.

LEARNING TO FLY

Thirty-five years before I was born, inventor and former circus worker George Nissen envisioned the first trampoline. He was inspired by flying carpets. George’s preliminary designs provided about the same amount of bounce you’d get from, say, leaping up and down on a hotel room bed. Nissen used rubber bicycle inner tubes as the next technological step, honing his design until he felt it was time to give his invention the ultimate field test: get some kids on it. The trampoline made its public debut at a YMCA camp, and the reaction among the first test pilots was so overwhelming that George was convinced he was onto something big. It would take a few years to attract a mass audience to try this new kind of fun, but George stuck to his guns and kept on bouncing. During the feel-good 1950s, the trampoline became an American phenomenon.

Wherever you are, George: Thank you.

I was raised on trampolines. I started jumping when I was two years old. To me, it was a big stretchy thing that made you go bouncy-bounce. By the time I was six I had backflips wired. From there I learned to do thirty backflips consecutively, with only one jump between each flip. Travis, Todd, Gina, and I would come up with different combinations and string our tricks together into runs. One of my favorite runs was a backflip and a half, landing on my back and launching into a front-flip to my feet, then following through into another flip. I had one trick I called a suicide. I would jump as high as I could and do a front-flip and arch as hard as I could, coming down staring straight at the canvas, then turn my head and land on my back right before I hit. This one never failed to frighten bystanders.

There are two disciplines in trampolines: the backyard style and the more formal gymnasium style. At one point when I was a kid, I enrolled in a gymnastics class, ready to demonstrate my skills for the instructors. They insisted I start out on the balance beam. After a week balancing on a narrow beam, I decided gymnastics wasn’t for me and reverted to backyard style. I owe a lot to the hours we spent experimenting on trampolines. Before I discovered bike riding, the canvas catapult was my halfpipe. It increased my equilibrium and taught me how to spot. It also developed my craving for individual sports, things that combined physical and creative abilities.

I think it was Todd’s idea to move the trampoline next to the slide. We worked our way up the steps on the ladder, until we were jumping off the top of the slide. This was a hoot, and we soon got a new tramp. We put scaffolding in between the two trampolines and learned to do flips over the scaffolding from tramp to tramp. We’d raise the bar on the scaffolding to see how high we could go as we flipped back and forth. Soon we built up the confidence to begin moving the trampolines apart, creating a gap: four feet, six feet, eight feet. Anything farther than eight feet across and over the scaffolding got pretty intense.

We also tried doubles routines on the trampoline. There’s a technique called double bouncing, where two people jump together to harness their momentum, using the canvas like a teeter-totter. If you do it right, you can really sky doing double bounces. Attaining maximum height was a conquest we never grew tired of. We would also hose the canvas down to make double bounce marathons and scaffolding sessions more challenging.

I was trying a double front-flip when things went crooked. I overrotated and ended up doing an extra half flip, and all my momentum was channeled into my head. I came down and whacked my face on the steel springs, punching through them and connecting with the metal support bars of the trampoline. It made a sound like a bell in a boxing ring, and the springs peeled my eyebrow back, putting a bone-deep gash just above my left eye. My dad took me to the emergency room, my head wrapped in a bloody turban. The ER doctor undid the bandages to reveal a slab of skin dangling from my ham-burgered forehead. As the doctor prepared his suture tray he said to us, “I don’t know if this is going to ever heal properly. There’s going to be extensive scarring, and …” At that moment my dad did something that made a dramatic impression on me and came in handy many times later in life. He told the doctor if he didn’t have the confidence to do the job to keep his hands off my head. We left the doctor standing there holding the needle and thread. Dad used his connections in the medical field to find the best plastic surgeon he could find, and my eye healed up fine—there’s barely a hint of scar today.

Thanks, Dad.

MEDICAL TIP FROM MAT

New doctors are often assigned to the emergency room shifts to give them plenty of experience dealing with a variety of traumas. Sometimes you get a great doctor; other times you get a green one. Trust me, it sucks to be somebody’s learning curve. Any time you find yourself in a situation where you need a doctor, remember that you have a choice in the matter. Insist on a doctor who has 100 percent confidence in the outcome of the procedure, and don’t be afraid to get a second opinion.

When I was growing up, my dad was in his heyday. His go-for-broke approach to life hadn’t faded with age, but it had become more refined. He was enjoying success as a businessman, and his leisure activities reflected his freewheeling, high horsepower persona. I don’t think my dad paid attention to how much money he made, or spent. He was good at spending it, sometimes too good.

He had a penchant for Porsches. Once he made a bet with one of his salesmen that he could leave their meeting and make it in time for my brother Todd’s football game, which started in ten minutes—and it was a twenty-minute crosstown drive to the game. He hit the road doing 110 miles per hour in his Porsche Targa, and took a shortcut. He didn’t see the ravine in the road built for the drainage of a lake. It was a twelve-foot drop and fifty feet across the ditch. With a slight pitch on the takeoff, it was a scene right out of a Burt Reynolds movie. Dad’s foot never left the gas pedal. He later said he was so high in the air he could see a little old lady in a white Chevrolet as he flew over her. He landed hard and blew out the motor mounts in the car, wasted the engine, lost the bet, and missed Todd’s game.

Dad loved to race his cars. He was in Dallas with my mom when some knucklehead in a hot rod goaded him into a street sprint. Despite the fact that my mom was his passenger, Dad accepted the challenge and the two cars tore through town. Dad drove like a nut until he was confident he’d tramped his opponent, then realized they were rapidly approaching a stoplight. He locked up the car sideways, screeching the tires and leaving melted Goodyear imprints smoldering in the intersection. Dad was stoked he beat the guy, but my mom was steamed. Her philosophy was to give you as much freedom as you wanted, but if you screwed up she held you responsible for your actions. She was definitely the voice of reason in our family. She helped balance out my dad’s stubborn side.

My dad went through a phase where he kept two Maseratis—one to drive and the other as a backup vehicle. He was in the habit of rocketing down lonesome highways at 150 miles per hour with one finger on the wheel while en route to his next sales call, or just to clear his head. Even with the two Maseratis, one was constantly wrecked and in the shop. He’d swap them back and forth between crashes, and eventually his hazardous driving in these cars is what made him find religion.

My dad didn’t need a motorized vehicle to test himself. Once, when he was away on business in Texas, he went out for some cocktails and found a guy with a bull. Dad expressed his desire to be a matador and seized the opportunity by the horns. Before the night was through, he was in the bullring waving a red cape. The fifteen-hundred-pound steer charged, and my dad quickly came to his senses. He ran for cover. Unfortunately, he made his move clutching the cape right in front of his chest. The bull zeroed in and rammed him dead center in the torso and almost blew out Pop’s lungs.

During another midnight rodeo escapade, Dad made a bet he could rope a calf while riding a bucking bronco. He got flipped off the horse a few times but climbed back on and rode him out, eventually winning the bet. Later he found out he’d split his sternum.

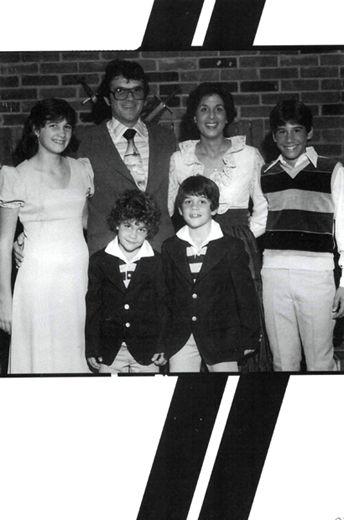

Mi familia

(left to right, top to bottom): my sister, Gina, Dad, Mom, my oldest brother, Todd, me, and my big brother, Travis.

Even during activities as innocent as going out to eat, my dad usually managed to take control of a situation. One day we were in a hurry and stopped at a Waffle House for a quick breakfast. As fate would have it, the food was taking forever. Finally my dad said, “We gotta get this food going” We all watched, shocked and sort of psyched as Dad marched into the kitchen and shooed the cooks away from the griddle. He wasn’t aggressive about it, but he definitely exhibited, how shall we say, extreme confidence. The bewildered chefs didn’t know what to do, so they got out of the way and let my dad make the waffles.

I was involved on a recon patrol with my squad, searching for the enemy deep in the bush. Canteens were the only source of water.

If I inherited my dad’s “no compromise” genes, the characteristic my brothers helped bring out in me is a tolerance for pain. I wasn’t a Kevlar-coated superchild. I bruised, bled, and cried like a typical seven-year-old. But I did begin to toughen up under the influence of Travis and Todd.