The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (98 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

There are, it is true, certain

natural

reasons for the precariousness of Soviet agriculture, and for the fact that its productivity is about one-seventh that of American farming. Although the USSR is often regarded as geographically rather similar to the United States—both being continent-wide, northern-hemisphere states—it actually lies much farther to the north: the Ukraine is on the same latitude as southern Canada. Not only does this make it difficult to grow corn, but even the Soviet wheat-growing regions endure far colder winters—and are subject to more frequent droughts—than states like Kansas and Oklahoma. The four years 1979–1982 were particularly bad in that

respect, and so embarrassed the government that it stopped giving details of agricultural output (although its average import of 35 million tons of grain each year provided a clue!). Even the “good” year of 1983 did not make the USSR self-sufficient—and it was followed in turn by yet another disastrous year of cold and drought.

124

Moreover, any attempt to increase production by extending the wheat acreage into the “virgin lands” is always constricted by frosts in the north and the arid conditions in the south.

Nevertheless, no outside observers are convinced that it is climate alone which has depressed Soviet agricultural output.

125

By far the biggest problems are simply caused by the “socialization” of agriculture. To keep the Russian populace happy, food prices are held artificially low through subsidies, so that “meat costing the state $4 a pound to produce sells for 80 cents a pound”

126

—which, for example, makes it cheaper for peasants to buy and feed bread and potatoes to their livestock than to use unprocessed grain. The vast amounts of state investment in agriculture are thrown at large-scale projects (dams, drainage) rather than at individual barns or up-to-date small tractors that an ordinary peasant might want. Decisions as to planting, investment, and so on are taken not by those who work the fields but by managers and bureaucrats. The denial of responsibility and initiative to the individual peasants is probably the single greatest reason for disappointing yields, chronic inefficiencies, and enormous wastage—although the wastage is clearly affected also by the inadequate storage facilities and lack of year-round roads, which causes “approximately 20 percent of the grain, fruit and vegetable harvest, and as much as 50 percent of the potato crop [to perish] because of poor storage, transportation and distribution.”

127

What could be done if the system were altered in its fundamentals—that is, a massive change away from collectivization towards individual peasant-run farming—is indicated by the fact that the existing private plots produce around 25 percent of Russia’s total crop output, yet occupy a mere 4 percent of the country’s arable land.

128

Yet whatever the noises about “reform” from the highest levels, the indications are that the Soviet Union is not contemplating following Mr. Deng’s large-scale agricultural changes to anything like the extent of China’s “liberalization” (see above), even when it is clear that Russian output is falling far behind that of its adventurous neighbor.

129

Although the Kremlin is unlikely to explain openly why it prefers the present system of collectivized agriculture despite its manifest inefficiencies, two reasons for this inflexibility stand out. The first is that a massive extension of private plots, the creation of many more private markets, and increases in the prices paid for agricultural produce would imply significant rises in the peasantry’s share of national income—to the detriment of the resentful urban population and, perhaps, of industrial investment. It would mean, in other words, the final triumph of Bukharin’s policies (which favored agricultural incentives) and the demise of Stalin’s prejudices.

130

Secondly, it would mean a decline in the powers of the bureaucrats and managers who run Soviet agriculture, and thus have implications for all of the other spheres of decision-making. While it is surely true that “individual farmers making day-to-day decisions in response to market signals, changing weather, and the conditions of their crops have a combined intelligence far exceeding that of a centralized bureaucracy, however well designed and competently staffed,”

131

what might that imply for the future of the “centralized bureaucracy”? If it

is

correct that there is a consistent, embarrassing relationship between “socialism and national food deficits,”

132

then that can hardly have escaped the Politburo’s attention. But from its own perspective, it may seem better—safer, certainly—to maintain “socialist” (i.e., collectivized) farming even if that implies rising food imports, rather than to admit the failure of the Communist system and to remove the existing controls upon so large a segment of society.

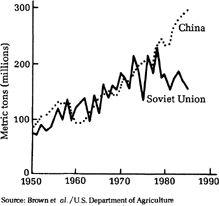

Chart 3. Grain Production in the Soviet Union and China, 1950–1984

By the same token, it is also difficult for the USSR to amend its industrial sector. To some observers, that may hardly seem necessary, given the remarkable achievements of the Soviet economy since 1945 and the fact that it outproduces the United States in, for example, machine tools, steel, cement, fertilizers, oil, and so on.

133

Yet there are many signs that Soviet industry, too, is stagnating and that the period of relatively easy expansion—caused by fixing ambitious output targets, and then devoting masses of finance and manpower to meeting those figures—is coming to a close. Part of this is due to increasing

labor and energy shortages, which are discussed separately below. Equally important, however, are the repeated signs that manufacturing suffers from an excess of bureaucratic planning, from being too concentrated upon heavy industry, and from being unable to respond either to consumer choice or to the need to alter products to meet new demands or markets. Producing masses of cement is not necessarily a good thing, if the excessive investment in it has taken resources from a more needy sector; if the actual cement-production process has been very wasteful of energy; if the final product has to be transported long distances across the country, thus placing further strains upon the overworked railway system; and if the cement itself has to be distributed among the thousands of building projects which Soviet planners authorized but have never been able to complete.

134

The same remarks might be made about the enormous Soviet steel industry, much of the output of which seems to be wasted—causing some scholars to marvel at the “paradox of industrial plenty in the midst of consumer poverty.”

135

There are, to be sure, efficient sectors in Soviet industry (usually related to defense, which can command large resources and

must

compete with the West), but the overall system suffers from concentrating upon production without much concern for market prices and consumer demand. Since Soviet factories cannot go out of business, as in the West, they also lack the ultimate stimulus to produce efficiently. However many tinkerings there are to assist industrial growth at a faster rate, it is difficult to believe that they will produce a sustained breakthrough if the existing system of a “planned economy” remains.

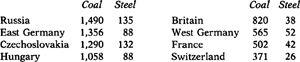

Yet if today’s levels of Soviet industrial efficiency are scarcely tolerable (or, judging from the harsher tone of the government, increasingly intolerable), the system is likely to be even more damaged by three further pressures bearing down upon it. The first of these concerns energy supplies. It has become increasingly obvious that the great expansion in Soviet industrial output since the 1940s heavily depended upon plentiful supplies of coal, oil and natural gas, almost without regard to cost. In consequence, the “energy waste” and “steel waste” in both the USSR and its chief satellites is extraordinary, compared with western Europe, as shown in

Table 46

.

In Russia’s case, this misuse of “inputs” may have seemed tolerable

when its energy supplies were so plentiful and (relatively) easily accessible; but the awful fact is that this is no longer the case. It may have been that the CIA’s famous 1977 forecast that Soviet oil production would soon peak, and then rapidly decline,

was

premature; nonetheless, Russian oil output did drop a little in 1984 and 1985, for the first time since the Second World War.

137

More alarming still is the fact that the remaining (and very considerable) stocks of oil—and of natural gas—are to be found at much deeper levels or in regions, like western Siberia, badly affected by permafrost. Over the past decade, as Gorbachev reported in 1985, the cost of extracting an additional ton of Soviet oil had risen by 70 percent and this problem was, if anything, intensifying.

138

Hence, to a large degree, the very extensive commitment by Russia to building up its nuclear-power output as swiftly as possible, thus doubling its share of electricity production (from 10 percent to 20 percent) by 1990. It is too soon to know how far the disaster at the Chernobyl plant will hurt those plans—the four reactors at Chernobyl produced one-seventh of the total Russian nuclear-generated electricity, so that their shutdown implied an increased use of other fuel stocks—but what is obvious is that it will both increase costs (because of additional safety measures) and reduce the pace of the planned development of the industry.

139

Finally, there is the awkward fact that the energy sector already absorbs so much capital—about 30 percent of all industrial investment—and that amount is bound to rise sharply. It seems difficult to believe the recent report that “a simple continuation of recent investment trends in oil, coal and electric power, combined with the targeted investment increase for natural gas, will absorb virtually the

entire

available increase in capital resources for Soviet industry over the period 1981–5,”

140

simply because the implications elsewhere are too severe. Nevertheless, the overall pattern is clear: merely to keep the economy growing at a modest pace, the energy sector will require an increased share of the GNP.

141

Table 46. Kilos of Coal Equivalent and Steel Used to Produce $1,000 of GDP in 1979-1980

136

Equally problematic, from the viewpoint of the Russian leadership, is the challenge posed in the high-technology areas of robotics, supercomputers, lasers, optics, telecommunications, and so on, where the USSR is in danger of increasingly falling behind the West. In the narrower, strictly military sense, there is the threat that “smart” battlefield weapons and advanced detection systems could neutralize Russia’s

quantitative

advantages in military hardware: thus, supercomputers might be able to decrypt Russian codes, to locate submarines under the ocean’s surface, to handle a fast-moving battle scene, and—last but not least—to protect American nuclear bases (as implied in President Reagan’s “Star Wars” program); while sophisticated radar, laser, and guidance-control technology might allow western aircraft and artillery/rocket forces to locate and destroy enemy planes and tanks with impunity—as Israel regularly does to Syrian (Sovietequipped)

weapon-systems. Merely to keep up with these advanced technologies requires ever-larger allocations of scientific and engineering resources to Russia’s defense-related sector.

142

In the civilian field, the problem is even greater. Given the limitations which are being reached in such classic “inputs” as labor and capital investment, high technology is rightly perceived as being vital for increasing Russian output. To give but one example, the large-scale use of computers could greatly reduce wastage in the discovery, production, and distribution of energy supplies. But the adoption of this new technology not only implies heavy investments (taken from where?), it also challenges the intensely secretive, bureaucratic, and centralized Soviet system. Computers, word processors, telecommunications, being knowledge-intensive industries, can best be exploited by a society which possesses a technology-trained population that is encouraged to experiment freely and to exchange new ideas and hypotheses in the widest possible way. This works well in California and Japan, but threatens to loosen the Russian state’s monopoly of information. If, even today, senior scientists and scholars in the Soviet Union are forbidden to use copying machines personally (the copying departments are staffed by the KGB), then it is hard to see how the country could move toward the widespread use of word processors, interactive computers, electronic mail, etc. without a substantial loosening of police controls and censorship.

143

As in agriculture, therefore, the regime’s commitment to “modernization” and its willingness to allocate additional resources of money and manpower are vitiated by an economic substructure and a political ideology which are basic obstacles to change.