The River at the Centre of the World (2 page)

Read The River at the Centre of the World Online

Authors: Simon Winchester

Tags: #China, #Yangtze River Region (China), #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #General, #Essays & Travelogues, #Travel, #Asia

Author's Note

Generally speaking I have used the pinyin form of the transliteration of the Chinese place-names and personal names that are used in this book. However, since this account deals with the past as well as the present – the Yangtze journey being deliberately chronological as well as topographical – there are occasions when it seemed to me much more suitable to use the old and officially discarded Wade-Giles form.

So although I visit the city of Nanjing, as it is presently known, I also make references to the Rape of Nanking and the Treaty of Nanking. Similarly, the river takes us to the grimy city that is now called Wanxian; but the infamous Wahnsien Incident took place there seventy years ago, and to refer to those remarkable events by the more modern name would make for greater confusion, I believe, than my small lexical inconsistency. In any case the names used in these and other examples sound to the Western ear usually more or less similar: only when the variant forms are very different – Tibet and Xizang, for instance, or Changan and Xian – do I interrupt the narrative to explain.

The name of the river itself is so complex and historically fascinating as almost to justify an entire chapter to itself. From this, however, I spare the reader – with the single caveat that the proper pinyin rendering of Yangtze is actually Yangzi, and the pronunciation, offered very approximately, is rather less

Yang-tzee

than it is

Young-zer

. But since the Chinese rarely if ever use either version, I have stuck with the most familiar, albeit barbarian, form.

As to how it became saddled with the non-Chinese name Yangtze – there is more mystery than agreement. Some nineteenth-century references speak of the word meaning ‘Son of the Sea’, while others refer to it as deriving from ‘the Blue River’ – and both of these interpretations are fairly reasonable, given that Chinese and its English transliterations enjoy an almost limitless elasticity. However, the most likely explanation probably results from a mishearing. Early western sailors on the river undoubtedly asked local boatmen for the name of their stream, and these boatmen – who may well have come from, or have been well aware of the great local influence of, the city of Yangzhou, which was then the greatest metropolis in the estuary region (and was where Marco Polo worked in the bureaucracy) – mouthed something to the effect that this was ‘the river of the Yang Kingdom’. Since Jiang is unequivocally the word for river, the combination of mumbling and elision of the words Yang and Jiang could quite possibly, to the untutored ear of a London-born sailor, have come across as Yangtzee-kiang. This name would have been reported back to the ship's captain; it would have eventually found its way into a report: the Admiralty would have issued orders relating to the said-named stream; and thus would geography, cartography and history have been gifted with an enduring new addition.

Common usage has it that a river's left bank or right bank is that which is seen on a downstream journey – the bank that is regarded from the point of view, as it were, of the flowing waters. I have tried to stick to this hydrographers' convention throughout my account. However, since my journeying was intentionally and relentlessly upstream this did produce moments that managed even to confuse me: I would see, from the deck of my upriver ship, a pagoda on the bank that lay on my

right

side, but I would have to note down that it in fact stood on the bank that, by convention, was actually the river's

left

. I have in places tried to lessen the confusion by mentioning north or south, or east or west, if doing so seems to clarify the situation; but I have to confess that this didn't always work.

*

The most difficult part of writing any book about the sad situation of contemporary China is not being able – thanks to the present government's unquenchable capacity for cruelty and revenge – to give the real names of many of the participants.

Many of the men and women whom I met along the four thousand miles and many months of this journey said things to me that were well worth including in the narrative; many others helped me in undertaking an expedition that was in no way officially sanctioned, nor even officially known about. I realized when I was writing, even if these people did not, that by relating their comments or the tales of their assistance in this book, I would cause retribution of some unpleasantly imaginative kind to befall them at some untold moment in their various futures. So I have, and with great reluctance, altered several names, and I have rendered deliberately vague one or two – but only one or two – locations.

Of the changes I have been forced to make I am sorriest of all to have to refer to Lily, my trusted guide and mentor, by this invented English name, and not by her real one – which, as well as enjoying the singular merit of being hers, is in its Chinese form very much more lovely, too.

Without Lily this book could not have come about, at least not in its present state. And yet to draw too much attention to her by writing of her as fully as I would like would be to invite a cascade of official wrath which she in no way either deserves or would be in a position to deflect. Lily is a remarkable and courageous young woman, the like of which China should be proud to count among its own. I am sure I am not alone in hoping that young men and women just like her will eventually find some way to inherit the management of their vast country, and thus one day, perhaps, to allow China to offer some kind of decently humanitarian future for its marvellous and almost unimaginably huge array of peoples.

Looking at the old river

From the opposite banks

Of a yellow ribbon

Like reading an ancient scroll –

Pictographs of man's flailing

Against the eddies

Of oft told histories…

Li Bai, Tang Dynasty

,

8th Century

Prelude

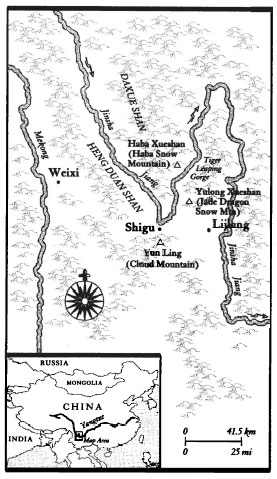

About a thousand miles downstream from the Yangtze's source – after it has performed nearly a quarter of its journey from the mountains to the sea – the river executes a most remarkable hairpin bend. Within the space of just a few hundred yards, a river that for hundreds of miles has been pouring relentlessly and indisputably southward slams head-on into a massif of limestone, ricochets and cannonades off it and then promptly thunders headlong back up to the north.

It is difficult to think of any other world-class river that does such a thing. The Nile performs a flirtatious little wiggle through the north of Sudan. The Lena engages in a long, slow curve near Yakutsk. No one can pretend that the Volga is die-straight, nor the upper reaches of the Ganges, nor even the Rhine. The Rio Grande has a ‘great bend’, but like all these other big-river bends, it is by Chinese standards laughably small. Nothing looks like the Yangtze in northern Yunnan.

The sheer sharpness of the turn is what is so peculiarly dramatic about it – the sudden whirl-on-a-sixpence, turn-on-a dime, now-you-see-it-now-you-don't kind of a back flip, a riparian volte-face of epic dimensions. It is so dramatically obvious that it shows up on even the smallest-scale maps – whole-world projections usually manage to display it: it shows up as a strange notch, a kink, a curious indentation in the passage of great waters. It seems almost artificial, as though some great deity had once said to this river alone: proceed thus far in this direction, and no farther.

They call it the Great Bend at Shigu Town, and the fate of all China has long depended on it.

For the sake of what the Chinese call the Middle Kingdom, it is just as well that the river makes the turn it does. For had it not done so, had it been permitted to flow on southward – as a glance at any map will show that it probably wanted to do – then it is certain there would never have been an entity that westerners call the Yangtze. There would never have been a river deserving of the name that the Chinese use: Chang Jiang, the Long River, or just Jiang,

The

River.

Had there been no bend, and had the waters been allowed to flow on, they would have passed inexorably, inevitably and quite tragically away from and out of China. They would have left the continent for the Pacific not in the huge embayment known as the East China Sea, but via the almost insignificant and palm- and karst-ringed inlet called the Gulf of Tonkin. They would have spilled from the land not in the great delta on which has been built the great city of Shanghai, but on the much smaller stretch of mud and shingle where man created the very much lesser twin cities of Hanoi and Haiphong.

But for the presence of the singular geological oddity at Shigu, the Yangtze would have flowed on down into what is now the valley of the Red River. Instead of joining the sea two thousand miles later at Shanghai, this river would have dribbled lazily and insignificantly where the treacly mess of the Red River does today; it would have been, for most of its foreshortened length, a river – sister to the Mekong – in the country that is these days called Vietnam.

And China would be left without the Yangtze. The tributaries that today join the Yangtze would have flowed elsewhere, probably never joining forces with a great mother-stream and making an attempt at mightiness. There still would be some big rivers in China's heartland – the Yellow River would flow on unaffected, as would the Pearl. But had not the limestone massif intervened at Shigu, there would be nothing so unimaginably vast as the river that slices through the nation's heart today. A China without such an immense torrent at its heart is almost impossible to contemplate.

And yet, but for this one event, this single happenstance at Shigu, it could so easily have been so. A map will show the evidence: it is incontrovertible – the Yangtze would have ended its days in undistinguished fashion. Palm-oil jungles would take the place of container ports, muddy villages instead of pagodas and palaces, small market towns instead of giant industrial cities.

The fate and condition of a China made riverless by such an event would be profoundly and unutterably different from the complicated, ancient, infuriating and unashamedly powerful China with which the rest of the world has to deal today. Which is why I have always found it odd that the little town of Shigu in Yunnan is by and large undistinguished, unvisited and unknown – a place that, if famed at all, wins its repute not for its remarkable geology, but for a long-forgotten battle in which an invading Tibetan army loses to a local people whose menfolk carry falcons, keep parrots as household pets and leave all their major decisions to the women.

Fascinating though this all may be, what Shigu should by rights be known for is the miracle of geography that took place there, and that allowed China to become watered by and divided by and unified by the most important river in the world.

There is naturally a rational explanation for the Great Bend. The sudden diversion of the river at Shigu is simply the work of tectonics, a geomorphological occurrence called river-capture, and more specifically, the work of the terrifyingly powerful and ten-million-year-long event known as the Miocene Orogeny. In China, though, rational explanation often bows before legend, and it does so impressively at Shigu. Children are taught in school that what happened in Shigu is the work not so much of tectonics, but of an emperor who was called Yü the Great, lived four thousand years ago and was so exercised by the thought of this mighty stream pouring out of China, and of the leaching of good Chinese earth out into the realms of the Annamese barbarians, that he set a huge mountain down at Shigu and blocked the river at its exit.

The hill Da Yü chose for this purpose is called Yun Ling, Cloud Mountain. It exists today, looming over the little town. One early summer's day, as I was halfway through a long journey upriver, I took an afternoon to clamber up its flanks and to gaze down at the bend it creates. I was quite alone. Few others bother to walk the hill: it is not very high, it offers no spectacular sport, and from all aspects it looks ordinary enough, with little to single it out from the chaotic jumble of hills that make up this part of the Empire.

But some – especially if they have hold of a map that shows what this mountain does, how it shapes the course of the river that skids up against its impregnable northern slopes – could build a plausible and persuasive case for Cloud Mountain being quite the most important mountain in the world. Its very existence, they would argue, whether it was created by tectonics, or by a long-dead emperor, quite simply and profoundly allowed both the Yangtze and China to be. Cloud Mountain caused the Yangtze to exist; and given the central role that the Yangtze has for aeons played in the creation of China, one can say without risk of too strong contradiction that it caused China to exist as well.

The hill is pretty, with a deceptively soft aspect, and when I walked up it the lower slopes were covered with rhododendrons in bloom, and with camellias and stunted camphor trees. It has, all told, a gentle ordinariness about it. But like so much in China, this is a cunning deceit: for in the formidable story of the Long River, and in the only marginally less formidable story of the Middle Kingdom, Yunnan's modest-looking Cloud Mountain plays an unsung but most extraordinary part.