The River at the Centre of the World (6 page)

Read The River at the Centre of the World Online

Authors: Simon Winchester

Tags: #China, #Yangtze River Region (China), #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #General, #Essays & Travelogues, #Travel, #Asia

I wrote to her in Shanghai, where the cruise company had its head office, to see if she might be interested. At first she was reluctant, unsure of her ability: ‘It will be difficult, I do not think I would be competent.’ More letters followed, and as the winter advanced and I explained the idea, she began to understand the possibilities. ‘I am quite intrigued… I doubt if such an opportunity would ever come my way again.’ A small practical doubt then crept into her mind: ‘I have only a month of holiday owing to me – but I have been looking at the map; surely to reach the headwaters will take very much longer… I might have to risk my job.’ Finally, as winter became spring, she melted: ‘I have decided to come with you… it is so difficult to get good travel gear here in China, so please bring me some sturdy boots, size 39, and a cold-weather jacket in a good fresh colour. I am mentally prepared for the venture… I just hope that I will be able to deal with any problems.’

I wrote her one final note, making certain that she would be able to come. ‘Don't worry,’ she replied. ‘I am a woman of great self-confidence. I do not want to rely on others. I have my own way of doing things. Once decided, nobody can make me change my mind.’ That, I thought, was the clincher. She, like no one else, could probably make this journey work.

It remained then only to get hold of some walking and camping gear, and a selection of good maps and charts.

I had hoped at first that I might get hold of some of the classic charts made by the British Admiralty – once the most accurate and most elegant ever made. Sedulously observant Royal Naval cartographers had been drawing maps of the Yangtze ever since Lord Macartney had been grudgingly permitted to sail along a few miles of the river in 1793. A second British expedition to China in 1816 under Lord Amherst had also resulted in some diligent mapmaking, and by the time of the First Opium War thirty years later, the river's mouth had been almost as well charted as the Thames, the Hooghly or the Hudson. The British tradition of making fine river maps continued well into the twentieth century – perhaps, I fancied, they would still be made, and still be of use.

I found a nautical chart agency in New York that stocked them – they had the Royal Navy charts of the Yangtze all the way up to Yichang, the city just downstream of the Three Gorges, 940 miles above the sea. But, the store owner warned me darkly, the maps' accuracy was no longer guaranteed, the data no longer reliable. Communism had put paid to free movement on the river since 1949, and the only extensive surveys since had been made by the Chinese, and their figures were kept broadly secret. Royal Naval survey vessels could no longer bustle along in the river's deeps and shallows, sounding and dredging by turns as they once were wont to do. But I bought the maps anyway, for séntimental reasons – they were very lovely, and I didn't mind too much if the depths were off by a fathom or two, or the distances wrong by the odd cable.

I also managed to find, in a secondhand bookstore, a 1954 copy of

The Admiralty Pilot for the Yangtze

– it was one of the great series of books that, bound in their distinctive and official-looking dark-blue weatherproof covers, describe in minute detail the coastlines of the entire world. These books are biblical in their authority and they display, to the delight of landlubbers, a fine dramatic economy in their prose style when talking about such matters as whirlpools and tide-rips or the dangers of Cape Horn. The

Yangtze Pilot

has been out of print since 1954: Communism had put an end to attempts to keep it timely and accurate too, and so the Admiralty scrapped it. There was a rather pathetic

cri de coeur

, I thought, penned inside one of its covers: civilian mariners making passage along the river could perhaps help, the surveyors pleaded, by writing in with any new information on any sightings of freshly formed sandbanks or other hazards to navigation. ‘A form (H.102) on which to render this information, can be obtained gratis from Creechbarrow House, Taunton, Somerset…’

But while nautical charts require visits by ships with echo sounders and tallow-ended lead lines, topographical maps are easier to find: satellites and high-flying aircraft perform most of the necessary functions for those who want no more than hills, rivers and roads. So there were plenty of maps available for the Chinese countryside on either bank of the river. No tourist map was worth having; but eleven of the huge sheets of the U S Defense Mapping Agency's Tactical Pilotage Chart series covered the entire river at a scale of 1:500,000, or about eight miles to the inch, and they were to prove useful, if occasionally frustrating. The smaller four-miles-to-the-inch joint Operations Graphics sheets, which American troops use when planning for war, cover the same ground – and, indeed, the entire world land surface – with a terrifying degree of accuracy.

The TPCs were easy to get: a charge-free phone number in Maryland, four dollars a sheet, credit cards accepted. The JOG sheets were more severely restricted, at least in theory. To have any chance of acquiring them I was obliged, starting a full six months before I was due to leave, to go through the curiously empty ritual of threatening a lawsuit under the Freedom of Information Act. This was the only way – an almost foolproof and face-saving device, I was told – with which to unlock all kinds of government documents, these maps included, from the grip of the censors.

A young paralegal was assigned by the Defense Department's chief counsel to shepherd my request through the bureaucracy. The guiding principle of her task, she explained to me later, was President Clinton's pronounced doctrine that ‘unless a specific statutory prohibition existed, forbidding the release of any map, the map could and should be made public’. Maps of remote areas of western China are supposed to be top-secret – but were there specific laws forbidding their release? To find that out was the young woman's appointed task.

The Pentagon, makers and prime users of the maps, took a disinterested view of the impending lawsuit, and passed the buck. The matter went to the Department of State, who objected strenuously. What if the maps fell into the hands of the Taiwanese? an official wanted to know. No matter, retorted my young helper – is there a

specific written order

forbidding the release of the maps? The State Department had to admit there was not, so far as they knew. It was up to the Central Intelligence Agency, and then the White House and the National Security Council, to have the final say. Officials in both these agencies tried equally hard to block the release. The Chinese, they said, should not be allowed to know how well America had mapped their country. No matter, said my paralegal once again – is there a

specific written prohibition

? No, said the NSC, there was not. No, said the CIA, there was not.

And that was that. A formal letter arrived the next day saying the ‘releasability status of the maps had been determined positively’. The young woman telephoned to say it had been the most difficult and stimulating Freedom of Information Act case for which she had ever been responsible. ‘I've learned a lot,’ she said. To celebrate her victory she had decided to waive all charges – I would have to pay none of her own legal fees, and none of the charges for the maps themselves. And a week later a buff official envelope arrived, enclosing two dozen astonishingly detailed maps of the far Upper Yangtze – maps of a scale and a supposed accuracy that would enable American and allied air and ground forces to go to war there. I felt a strange sense of privilege holding them in my hands: few others could have ever seen them; and had I made the request in almost any other country – Britain included – there is little hope that I would ever have acquired them. The Clinton White House, I thought, had some admirable qualities.

My only concern on having the maps was that the Chinese (who restrict their own maps with understandable severity) might, if they found these on me, either confiscate them for their own use or regard me with the gravest suspicion for possessing them. ‘Don't worry – they'll think you're a spy whether you have maps or not,’ Lily wrote reassuringly when I mentioned them. ‘Where we're going, any round-eye is thought to be up to no good.’

After that all was simple. My days were dominated by the delights of rummaging around in camping stores for gear: I made myself popular indeed with the owners of a new and at the time not very successful shop close to the Appalachian Trail in Kent, Connecticut, by buying a new Kelty rucksack, a good sleeping bag guaranteed to give comfort at minus twenty degrees, an inflatable sleeping pad, a new down ski jacket (in the ‘good fresh colour’ of bright red for Lily), two new pairs of Vasquez boots, innumerable pairs of socks, two tiny flashlights, a spare Silva compass, fingerless gloves, two sets of Ex Officio dry-in-an-hour shirts and trousers, a his and hers set of Oakley high-altitude sunglasses and a pair of smart telescopic German walking canes (which proved entirely useless for anything except driving away wild dogs in Tibet).

To this collection I added my own Leica M6 camera, a Sony microcassette recorder with a remote-control switch, a tiny shortwave radio receiver and my own home-grown first-aid kit with its assortment of hypodermic syringes, morphine, painkillers and broad-spectrum antibiotics – all obtained from friendly doctors who go in for expedition medicine and don't trouble with such niceties as prescriptions. Two bottles of SPF 45 sunblock, some equally strong lip salve (I had been warned that the summer sun in Qinghai province could sear the lips from a camel), insect repellent and a trusted and battered hip flask made up the pack, which, when fully tamped down, weighed a quite acceptable fifty pounds.

I hoisted it onto my back, whistled down a taxi to Kennedy, and twenty hours later was through customs at Hong Kong's Kai Tak Airport. Two days later still, having made a series of complicated arrangements by telephone and having received a somewhat dubious series of assurances, having a new six-month multiple-entry ‘F’ class China visa stamped in my passport and a few wads of American dollars tucked into various waterproof pockets around my person, I stepped onto a boat.

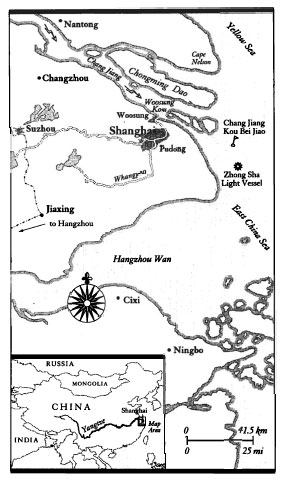

I had a rendezvous arranged at a very precise point in the East China Sea. It was at position 31°03.5' N, 122°23.2' E. What was there, according to the charts, was known to China coast mariners, and now to me, as the Chang Jiang Kou Lanby – the Yangtze Entrance Large Automatic Navigation Buoy. Given fair winds and calm seas I expected to arrive at this point, or thereabouts, in three days' time.

2

The Mouth, Open Wide

The bridge telegraph clanged backward to ‘Stop all engines’, the roar of our cathedral of diesels promptly softened to a low burble, the rusty white ship lost headway and hissed to a halt. The world then fell silent. We rocked listlessly on an invisible swell. The air was heavy, without movement. Stripped of the breeze of our own making, it became quickly very hot and sultry, and with no relief coming through the punkah louvres, the cabins became unbearable. The decks were scalding too, except where we could find shade – but even though the mid-morning sky seemed brassy and bright, the glare was without focus and there was neither sun nor shadows, so dark places were hard to find. We drifted in the current, rocking slightly, waiting for something to happen.

I stood at the bow and looked for China. But it was as though we had come to rest inside a cloud made of sweltering cotton wool. Everything was a featureless grey glare, stripped of any points of reference. There was no horizon, there were no landmarks or seamarks, and it was difficult even to see the waves, though I could hear them splashing untidily on the scorching iron of our plates below. The East China Sea is not known for frets or haars: but it has days like this of boiling-porridge invisibility, in which haze and dew point and temperature and a warm sea-mist combine to create a non-dimensional world, a place in which a stranded sailor could well go mad.

We had already passed the Chang Jiang Kou Lanby. It is a sort of cut-down lightship – not long ago there had been a real ship anchored here, bright scarlet, with the words

Ch'ang Jiang Light Ship

in white on the hull. It had been full of sailors and light keepers and wick trimmers, men who might wave a welcome or a farewell to a vessel that passed and sounded her siren. But China has taken advantage of automation like almost everybody else, and the distant markers of her busiest waterway are now all run automatically, by computers, their performance monitored by men high in darkened and air-conditioned shore-side towers, dozens of miles away.

Nonetheless, this massive buoy, fifteen feet above water and weighing a thousand tons or more, had a certain shabby romance about it, marking as it did the place where the great inbound ships leave the ocean proper, and begin their entry to China. So as we passed I took due note of its bright red hull, its white light tower, the muffled sound of its bronze bell. At the same time the master was given new orders by radio: we were to make a further five miles west, heave to and await fresh instructions.

This new spot, a glance at the charts suggested, seemed to be where one is supposed to pick up a Yangtze River pilot. Back in the old days – people who knew the old Shanghai use the phrase frequently – the river pilots used to be swashbuckling fellows, and they had a table permanently reserved for them in the bay window of the Shanghai Club. They alone could take vessels up and down the hazardous waters between here and the docks by the city Bund,

*

and they commanded prestige and high wages. But these are less dashing times, and the relevant portolanos, the blue volumes of

China Sea Pilot

– Oxford-dark from the Admiralty, Cambridge-light from the Pentagon – are a little vague as to their haunts today. London gave the right latitude and longitude and said that a boat ‘from which two or three pilots may embark’ was generally to be found within a mile or so of it. Washington's navigation instructions said the pilots would lurk in perhaps two places, one of them about four miles north of the closest lighthouse, the other three miles south. But where we were now bobbing and rolling there was no pilot boat, no buoy, no lighthouse: nothing. And so we waited, the static from the bridge radio dull and irritating, like frying fat.

Then with sudden urgency this static was interrupted. A voice in Chinese greeted our ship by name. It broke into English. ‘Our Inspection Cruiser Number Two is now coming to your starboard quarter. Kindly board your passenger to our port bow. We will arrive in three minutes. Please get ready. Please attend.’

It was time to say farewell. I said my thanks to the captain who had given me the ride this far – he was bound for other ports far away – and I ran to the poop, where a gang of sailors were uncoiling a rope ladder. On the horizon was a small black-and-white boat, its bows rearing up as it headed towards us at speed. It came closer and closer, then its prow dropped as it cut back power and it sidled slowly in and up to the dangling rope. From the foremast the boat was flying the blue-and-white burgee of the Yangtze Harbour Superintendency, and from the stern, the red, five-starred flag of the People's Republic. Two young Chinese sailors were standing on the foredeck and with them, waving up at me, was Lily.

‘They're certain you're a spy!’ was the first thing she shouted. ‘All very irregular, us meeting out here.’ She grinned wickedly as she helped me down from the swinging ladder and watched me lug my rucksack onto the bridge. ‘You'll never know

what

I had to do to persuade them to allow you on board.’ She said no more, but stowed my bags under a table. All was Bristol-fashion within a minute: the sailors then let go fore and aft, and the two boats parted company.

Our siren gave a yelp, and the rusty white transport that had brought me here replied with three blasts on her horn. Her screws began to thresh up the green water, and with her rudder set hard to starboard, she started to push sedately away to the northeast. The Inspection Cruiser Number Two – the

Shu-in Lo

– then set her own course due west, right into the mouth of the Long River. She was making for the point that is customarily regarded as marking the Yangtze River's outward end – the proper starting point for the long upstream journey.

There was still no sign of land. The bridge radar showed a fuzzy image ahead on either side, but though I squinted hard, I could see nothing except the brown-grey blur where sea met sky. We chugged inward, twisting this way and that to avoid shallows. After a while we slowed again, and ahead of us, alone in the emptiness, was another very large buoy.

It was smaller than the Gateway Buoy, but if the satellite navigator's readout was correct, then it had an importance all its own. The cruiser captain started pointing at it, jabbing his finger and shouting, ‘Zhong Sha! Zhong Sha!’ It was just as I thought, confirmed by the list of lights on the chart table: this was what the world's mariners agreed was the position of the mouth of the Yangtze River, the place where estuary encounters ocean. It is marked by twenty tons of floating and barnacle-crusted metal, a white flashing lamp, a bell and a somewhat prosaic name: Zhong Sha, or Middle Sand Light.

It was swiftly evident, too, that this structure did lie more in a river than on the sea. The tide was slack – we had organized our rendezvous with the inspection cruiser while the waters were as quiet as possible, just in case. But the waters here, only a little farther west, were not quiet at all – they were streaming hard against the great buoy, their force tilting her a good five degrees from the vertical. A rich coffee-coloured wake, murkier than the colour of the ocean behind, stretched fifty feet from the buoy's downstream side. Up close I could hear the bubbling and chuckling of the water rushing past, doing two knots at the very least. For a moment I thought the buoy itself was moving at two knots, towed by some underwater force, perhaps a shark. But then I realized what it was: even out here, where there was no land visible and no evidence that land was anywhere near, the river,

the

River, was running.

And running with waters that had flowed a very long way indeed. The generally accepted length is 3964 miles (6378 kilometres, and nearly ten thousand Chinese

li

): the waters have seeped and trickled and gurgled and foamed and roared and slowed and sidled and lumbered all the way here from Tibet – almost from China's faraway frontier with India. This urgent brown stream, heavy with silt particles that even now were drifting down to the seabed and making fresh land below us, was bringing soil all the way from the Himalayas, and leaving it here on the floor of the East China Sea.

Blue ice had thickened and shattered the granites of summits, ice-milk streams had emerged from distant glaciers, crystals of mica had glinted in salmon-rich headwaters, and all had merged with other sands and muds and gravels, and had flowed down from the plateaux for hundreds upon hundreds of miles before casting itself down here, fifty feet below on a dark ocean floor in the upper tropics, beneath the shadowless iron of a rusting light buo.

There was nothing languid in the transfer, nothing casual about the way that these waters flowed and slowed and deposited their long-hauled baggage. Like China herself, the river here seemed to be surging along, forging robustly out into the ocean, making new Chinese territory with deliberate purpose, even so far from shore. Hydrologists suggest she journeys outward on a prodigious scale: 1.2 million cubic feet of water gush from the Yangtze's mouth every second, and more than twice that amount each August and September, when the snowfields have melted back and the summer rains have dumped still more water into her seven hundred or so furious tributaries. Each year a total of 244 cubic

miles

of water slide out from what the radar insists is the river mouth: a veritable planet of water, of which each side is as long as the distance from New York to Washington, or from Oxford to Amsterdam.

The Yangtze journeys hugely, and she travels heavily. The same science that produces the figures for her flow calculates that her waters pick up and carry 500 million tons of assorted alluvium every year, and dump 300 million of those tons onto the seabed. (The rest stays, left inland – a swamp here, a drying patch there, a new cliff or a swelling eyot.) The result is that the Yangtze has a formidable delta, pushing itself out to sea at the quite respectable rate of 25 yards a year. All to be tilled and cropped by the rice farmers of China's easterly province of Jiangsu, of course – fortunate men indeed. The gradual abrasion of faraway mountains keeps on giving them brand-new territory, two and a half inches more of it every single day.

This steady eastward expansion has over the centuries given eastern China a comfortable, corpulent profile, so that on the map it seems puffed up like a pouter pigeon, or a diner-out – though rather more Pickwick than Falstaff. The place where the Yangtze pushes outward to cause it all is deceptive, however: the great notch that looks as though it should be the Yangtze's embouchure was once fed by three huge branches of the river, with the fourth in its present channel. But silt and sand choked the three southerly streams, and the accelerated flow in the northern branch favoured and deepened that one. In the seventh century the last of the southern delta streams was closed for good, and the Yangtze has been flowing along its present course, as a single, vastly wide river, for the thirteen subsequent centuries. The gaping mouth below provides a coastline for the old ports of Ningbo and Hangzhou; but it is, by the Yangtze's standards, quite dry.

As we moved hesitantly through the mist, so evidence of land slowly started to appear. Two white butterflies, a dragonfly. Flotsam on the water – fragments of Styrofoam, pieces of lunch containers from some distant city. A carcass, probably pig. I very much hoped it was pig, and turned back quickly to make sure, but it was lost in our wake. Then the riverbanks began to come into view – the mist and hum of coastal China at long last, even if only vaguely in the distance, first on the starboard beam, then off to port.

A hundred years ago almost every piece of this land had a recognizably English name – the Royal Navy surveyed these coasts well – and so once I might have been able to pick out Saddle Island, Parker Island and House Island, Drinkwater Point and, marking the northern entrance to the river, Cape Nelson.

*

But these names have all now vanished from the charts: the islands are called now what they have in fact been called for thousands of years – Chenqian, Shengsi and Heng Sha. Drinkwater is now simply Dong Jiao, East Point. As for the hero of Trafalgar, his promontory (not visible from here, since the estuary is fifty miles wide) has long since been changed back to its rightful, if more prosaic title: Chang Jiang Kou Bei Jiao – Long River Gateway, North Cape.

As the islands started to close in, so too, did the ships. A thousand ships pass in and out of the Yangtze estuary every day. In any river entrance their presence would be carefully noted, for safety's sake; in Chinese waters they are noted, and watched, for the security of the State as well. Captain Zhu, master of Inspection Cruiser Number Two, swept the horizon with his glasses. ‘Anyone who looks unusual, we go and see him,’ he said. ‘And if very unusual, we turn to' – and he jabbed his finger off to port, to where a dark grey corvette was speeding past, a ship armed with two obvious guns, one for‘ard, the other aft, and with a forest of radio aerials grouped around her mast – ‘the Chinese Navy. She guards our river. Just in case.’