The River at the Centre of the World (42 page)

Read The River at the Centre of the World Online

Authors: Simon Winchester

Tags: #China, #Yangtze River Region (China), #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #General, #Essays & Travelogues, #Travel, #Asia

The guidebook I had with me struck a rather irritable tone about Dr Ho and Bruce Chatwin's somewhat overripe profile of him as ‘the Taoist physician in the Jade Dragon Mountains’. The publicity had gone to his head, said the book: now everyone wrote about him, everyone visited him, he was formidably wealthy compared to his fellow villagers, and he never let visitors pass without impressing his fame upon them. But where exactly was he? No one here seemed to know who he was; if he existed at all he had evidently gone to ground.

We retraced our steps, frustrated. After twenty minutes we found ourselves back in the stone-paved central piazza and struck off to the north. Two hundred yards along the way there was an almond tree in the middle of the road, and from behind it, as if responding to a stage manager's cue, stepped a slight man dressed in a blue wool cap and a long white doctor's coat.

‘My friends, welcome!’ he said, in the familiar and oily way of a man who is about to sell you something you know you don't want. ‘How very good of you to take time to visit my humble village. You have time to come to my little home?’

Dr Ho had found us. His having done so there was now no getting away from him. He looked quickly around to make sure there were no other potential clients coming up the street, then bundled us into the front room of his cottage, beneath a small sign that said Jade Dragon Snow Mountain Chinese Herbal Medicine Clinic. It was by no means an extraordinary house: the walls were of wood and a dark reddish mud from which poked tiny bristles of chaff. Inside there were shelves of papers and a desk covered with vials and bags of seeds, and there was a pleasant smell, like an old Irish Medical Hall.

Dr Ho spoke English quietly, just comprehensibly, telling us his life story in the compressed manner of a telephone pitchman who knows that at any moment his listener may put down the receiver. If ever I showed a sign of wearying he would put his hand gently on my knee. ‘Wait for just a moment, kind sir you have come a very long way to hear my story.’ He said he had learned his English at the nearby American air base: but it sounded quite Dickensian, not at all as though he had been schooled by the men of the Flying Tigers.

The Cultural Revolution that swept through Lijiang came as something of a mixed blessing for Dr Ho, who had returned to the town from Nanjing after falling ill some time in the early 1960s. The Red Guard detachment assigned to this part of Yunnan selected the doctor promptly for

reform through struggle

, or some such madness: he was immediately suspect for no better reasons than his ability to speak, not only fair Dickensian English, but an alarming number of other foreign languages as well, a skill that in the eyes of the Guards rendered his commitment to Han supremacy and Maoist ideals very far from certain. So his house was ransacked, suspect goods and books were confiscated and he was forced outside to work, set to tilling the mountainside and making orderly fertility out of wild Yunnanese fecundity.

But what the Guards did not realize was that the work they had set Dr Ho as punishment brought him into contact with the makings of a new and very profitable career. Working in the fields halfway up the Jade Dragon Mountain, he came across samples of some of the rare and unusual plants that forty years before had been studied assiduously by Joseph Rock. Dr Ho knew Rock's work and he recognized the possible importance of the flowers and shrubs that were growing in such abundance on these slopes.

He started to collect them, keeping them well away from the scrutiny of his minders, bringing them back each night to the small plot of land behind the house. There he began to grow them in pots and under glass. Thus was born the tiniest and most exotic of physic gardens, with strange and exotic samples of botany that exist to this day. As part of his discourse Dr Ho takes visitors to see them: there is a lichen guaranteed to cure shrunken ovaries,

*

the root of an orchid that is said to be good for migraine, a delicate green grass known as heaven's hemp – said to be peculiarly efficacious in seeing off bladder problems – and something called

Meconopsis horridula

, which, as its name half implies, works wonders for the temporarily dysenteric.

Dr Ho ground his plants to powder and soaked them in hot spring waters – trying them out on the villagers, varying the amounts and the mixes depending on the ailments presented and the age and sex of those he treated. Before long he had a following: the Chinese have always been eager for natural cures, for their own version of the Ayurvedic arts practised farther west, and Dr Ho's discoveries on the mountainsides seemed to work wonders, either from their chemistry or from their placebo effect.

He next combined his newfound pharmaceutical skills with his professed lifelong commitment to the way of Taoism – a philosophy that in any case sets great store by internal hygiene, the quest for immortality, internal alchemy and healing. And in 1985, formally and with some ceremony attended by Taoist priests, he established himself as a full-blown Taoist herbal healer. He sat back and anticipated a late middle age of well-meaning obscurity. What actually happened, however, was that a few months after setting up shop, and by pure chance, he was visited by the Adonis-like figure of Bruce Chatwin, his hand-tooled leather rucksack on his back, who swung into town with his pencil, notebook and an assignment from an American newspaper. Chatwin plucked Dr Ho from nowhere and cast him into the blinding spotlight of thoroughly respectable fame.

Whether or not there is any therapeutic value to any of Ho Shi-xiu's seemingly limitless range of teas, decoctions, infusions and tisanes, there is no saying – there have been no laboratory tests, so far. But such was Bruce Chatwin's following that, on his say-so alone, a string of the distinguished and the gullible promptly started to stream into Baisha to seek solace and comfort and the botanical assistance of Dr Ho's tiny clinic.

The doctor, a man not at all backward at coming forward, presents to anyone who is interested – and to most who are not – a thick stack of files and visitors' books that demonstrate the vast number of the great and the good, as well as the ordinary German tourists and Japanese bus-tour groups, who have come a-calling. There were the signatures of British ambassadors by the score, of television personalities like Michael Palin and John Cleese (‘interesting bloke – crap tea' he had written), of writers like Patrick Booz, of society ladies from the Upper East Side, and of regiments of Californians and health nuts from Oregon, Montana and the hills of Bavaria. There were newspapers articles in all known languages, preserved in folders of cellophane: he took them reverently from the stacks, offered them for viewing as though they were fragments of the True Cross.

Finally he peered at me, placing his wispy little white beard close up against my face and examining my skin and eyes. He leaned back:

‘Blood pressure, anxiety, loose bowels,’ he declared. And though I protested that I had none of these afflictions – although my daily inspection of the leavings below dozens of Yunnanese hole-in-plank lavatories had convinced me that the latter problem was endemic in rural Chinese life – he pressed a bag of powder into my hand, then a leaf or two and a twig, which he pressed between the pages of the book I was carrying, and cocked his head on one side.

‘These will clear up all your problems, I have no doubt,’ he said, and cocked his head again, an expectant expression on his impish face. I twigged: he wanted cash, and Lily counted out some ten

renminbi

bills into his hand, one bill, then two, then five – until, finally he smiled, closed his fist on the money and stood up.

‘You have been so kind to give me of your valuable time,’ he said, in as non-Flying Tigers a patois as it is possible to imagine. ‘I hope you will tell your friends to come and visit me too.’ Not

I hope you will come back

; just

I hope your friends will come

, listen to my spiel, hear about my fame, listen to my diagnosis of a life of diarrhoea and dyspeptic discomfort, buy samples of my potions and make me richer, and pass it on in due course.

He was a rogue, I thought – a lovable rogue of a snake-oil salesman, an amiable bit player in a circus of a grand tradition. He and his Taoist wizardry had taken me for fifty quite affordable yuan. But he had taken the late and much missed Bruce Chatwin, I thought, for really rather more.

13

The River Wild

During its 3964-mile passage from the fringe of glaciers at the foot of Mount Gelandandong in Qinghai province, to the navigation buoy on the East China Sea, the Yangtze drops 17,660 feet – three and a third miles. Most of that drop occurs, as is the case with almost all rivers, in its first half. Between the glaciers and the distillery city of Yibin – a distance of 1973 miles, which happens to be almost precisely half the distance between the source and the sea – the river drops very nearly 17,000 feet – almost all of its total drop, in other words. Below Yibin the river is wide and generally placid: it is

flatwater

, as mountain boatmen like to say.

But above it, on that first half of the river, the water is anything but flat. Above Yibin, every river mile of the Yangtze sees its waters falling an average of eight and a half feet. That is very steep by the standards of any major river. It is worth noting that the Colorado slides down along a similar gradient as it passes through the Grand Canyon – but manages to do so for only for 200 miles. The Yangtze, by contrast, keeps going down and down at the same average rate for fully 1900 miles.

The upper half of the Yangtze is, in other words, for almost all of its length, a very turbulent, very fast and very steeply inclined body of water indeed. Once it has been properly established as a big river – once the dozens of lesser source streams have braided and knitted themselves together to begin the process of emptying the high Tibetan Plateau of all available running water – tens of thousands of cubic feet of water course every single second down it towards the sea. And though on average these gigantic quantities of water fall more than eight feet in every mile, it must be remembered this is on

average.

In some places the waters sidle gently between low banks and sandy beaches. They pass by silently, they give sanctuary to wading birds, they provide watering holes for antelope and bear and other animals of the high cold plains. The waters are icy and clear and shallow; the river is wide; there are low sandy islands; and looking down from a boat one can see huge fish waving slowly in the current. Places like these are rare and beautiful; and their beauty has an ominous quality, since invariably beyond the lip of the downstream horizon everything changes, and what is placid up here becomes down there a place of speed and foam and spray and, for any humans caught there, a place of matchless danger.

At these much more numerous other places – both on the River of Golden Sand and on its upstream extension that the local Tibetans call the Tongtian He, the River to Heaven – and once the Tibetan Plateau's encircling hills have been breached and the waters begin to roll inexorably down towards the ocean, the vast volumes of water steadily transmute into terrifying, awesome stretches of river where the power and fury of the rushing Yangtze become barely imaginable. All these millions of tons of roaring water are suddenly squeezed between gigantic cliffs, are contorted by massive fallen stones and by jagged chunks of masonry, and they sluice and slice and slide and thunder down slopes so steep that the waters hurtle down ten, twenty, fifty feet in no more than a few hundred furious yards.

In places like these the water is not so much water as a horrifying white foam – a cauldron of tortured spray and air and broken rock that is filled with the wreckage of battered whirlpools and distorted rapids and with huge voids of green and black, the whole maelstrom roaring, shrieking, bellowing with a cannonade of unstoppable anger and terror. The noise is almost more frightening than the sight: the sound roars up from the cliffs, echoing and resounding from the wet rocks so that it can be heard from dozens of miles away, a sound of distress like a dragon in pain.

These stretches of wild water are nothing at all like the troublesome boils and shoals and whirlpools of the Three Gorges, across which trackers were able to haul the great trading junks, and where Cornell Plant and Archibald Little eventually triumphed with their iron boats: these are upriver rapids where any survival is impossible, where any craft sucked in would emerge only as matchwood, and where any passengers or cargo swept down would be pulverized by the ceaseless might of the roaring waters. These are the Upper Yangtze's rapids, and they are worse than any others in the world.

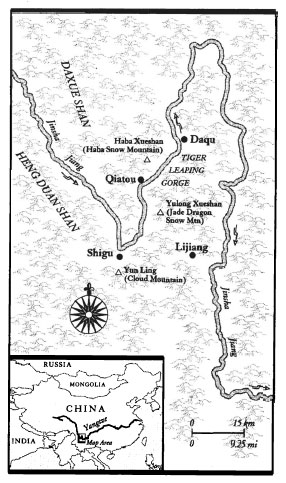

There are many of them, all unutterably dreadful, all formidably dangerous. But none is more dangerous and dreadful – nor more spectacular and unforgettable – than those in the gorge near Lijiang, where the river squeezes itself through a twelve-mile-long cleft that in places is no more than fifty feet across: narrow enough, some say, for a tiger fleeing from a hunter to have once jumped clear across. This notion is almost certainly quite fanciful, but the name has stuck – Hutiao Xia, Tiger Leaping Gorge, unarguably the most dramatic sight on the entire route of the river.

During these twelve miles the river falls at least six hundred feet – by some estimates, a thousand. That means it falls at the rate of between fifty and eighty feet each mile, a drop with more of the characteristics of a waterfall than of a river rapid. According to the Chinese there are three main groups of white water in the Gorge and twenty-one separate rapids. All of them are dangerous: two in particular, one close to the beginning of the Gorge itself, one halfway down, are truly terrifying.

The river courses along a natural fault line, tearing through rock that has already been crushed and weakened by the tectonic forces that have shaped this geologically chaotic corner of the world. Near-vertical cliffs of limestones and granites, porphyries and slates, soar directly up on either side of the stream for fully seven thousand feet; the mountains of which they are faces rise behind them to twelve thousand feet, and from the dark gorge shadows below one can peer up into the narrow strip of blue sky and glimpse snow and ice sparkling on the upper slopes.

There is a pathway clinging to the left bank of the river, and Lily and I planned to walk down it. We started on the Gorge's upstream end, at the bridge at a hamlet called Qiatou, where the river flows silently and placidly under groves of weeping willows and looks for all the world like the Thames at Bablockhythe. There was little indication here that things were about to change, except that the river's progress seemed to be blocked a few hundred yards ahead by the huge wall of mountains rising sheer to the north of the grubby little village.

But soon there turned out to be another clue: while not so long ago Tiger Leaping Gorge was rarely seen by westerners,

*

today the local authorities have become only too well aware of the profit they can make from those outsiders who have a fondness for strenuous journeying, and so they have built a sort of turnstile on the path and employ an old man to sell plastic tickets to walkers. Ours read, Hutiaoxia Tourist Scenic Spot Management Office of Zhongdian County and it had a sketch of an improbably long tiger jumping across an improbably narrow defile between cliffs. Permission to undertake the walk costs about a dollar, and the man told me he sells about twenty tickets a day in the summer.

‘Be very careful,’ he said morosely. ‘Two killed already this week.’

The path, an old miners' mule track, is hewn out of an almost vertical cliff face. The mountain rose mossy and dripping to our left, the cliff wall dropped off sheer to our right, directly into the river. And while the path more or less followed the contour line, the river itself began to whip down the dizzying slope, starting the fall of nearly a thousand feet down the twenty-one gigantic sets of rapids. This meant that the cliff on our left-hand side became ever higher as the river fell away. We hugged close to the mountainside, imagining what might happen if we strayed too close to the other side, a slippery piece of rock, a gust of wind…

About a mile in, as the walls of the Gorge began to close and the sun was blotted out by the walls of rock, we crossed a pile of blinding white debris, the spoil heaps of a marble quarry. Where was the quarrying? I wondered – and as I did so a van-sized piece of rock whistled down from above, crashed onto the spoil heap, bounced off it and then hurtled down over the edge. I heard a vast splash from below. The quarry, I realized, was five hundred feet above our heads, on the side of the mountain.

This was where the walkers – both North Americans, it turned out – had been killed three days before. They had been doing just what we were doing – walking slowly and carefully along the tiny track, not daring to venture too close to the river side. Suddenly and without any warning a huge piece of marble, dislodged by a careless worker up above – most of the quarry workers were prisoners, it was said, and could be expected to take an understandably cavalier attitude to the safety of those around their enforced workplace – slammed down on top of them, and dashed them away and off the path and down into the river below. They may have been killed by the rock; they may have died in the fall into the river; they may have been drowned. Whatever: their bodies, mangled beyond recognition and with every bone broken, were found at the lower end of the Gorge later that evening.

We walked even more nervously, keeping a hundred yards apart so that if one of us was hurt, the other might survive. From time to time the path petered out and we were clambering over soft talus that would slide over the edge as we shuffled through it, and would threaten to drag us with it. Once in a while we met walkers coming the other way: they looked white-faced and nervous, and greeted us with queries that we echoed to them:

What's it like ahead?

Then the path widened, and there was a small stall built of rock where a young Moso man was selling soft drinks. A steep path led down from here, and someone had suspended a rope alongside it to give walkers added purchase: it went down to the bellowing and spray-drenched side of the worst rapid of all, a place where the river is cinched into its tiniest cleft and where a mansion-sized pyramid of black limestone stood in the middle of the stream, splitting the roaring white waters into two, like a half-horizontal Niagara ceaselessly churning and bellowing through the defile.

We went down and stood alongside it, struck dumb by the thunderous might of it all. This, of the twenty-one measured rapids of the Tiger Leaping Gorge, was probably the worst, the meanest dog of all. Great torrents of white and green water hurtled towards us, taking boulders and spars and trees along with the flood as though they were feathers and balsa-wood sticks. This was the quintessence of the Tiger Leaping – the rapid we had come to see, where the river showed itself as a thing of raw and unimaginable might. This was a place where no human being could ever pass. Or so I once had thought.

Someone had managed to get onto the rock in midstream, for a start: he or she had written the characters for

bu

and

tiao

– tiger and leap – in vermilion paint on the rock's most prominent surface. How this unknown painter – or this graffiti artist, or this vandal, depending on the viewpoint – had managed to get across, to daub his paint and get back without being swept away is an achievement that beggars belief.

But man has an unquenchable eagerness for the conquest, as he likes to put it, of such challenging places, Mao Zedong had swum across the Yangtze down at Wuhan, and so had conquered it, in a manner of speaking. Other men, and at later dates, had tried to voyage their way down the entire length of the river, paddling it in specially strengthened boats. This was their version of conquest; those who tried were among the best and the worst of humankind; their efforts, in which the puniness of man was matched against the strength and caprices of the river, led to some success and also to a great deal of painful failure. Tiger Leaping Gorge – and in particular this huge rapid near its beginning, officially known as the Upper Hutiao Shoal, with a sixty-foot drop through two suicidal pitches – was where that failure had been most vividly demonstrated.

The ‘conquest' of an

entire

river demands of course that one knows where the river begins and ends – knowledge that, for the world's big rivers, can be notoriously difficult to acquire. Close to their beginnings big rivers have a habit of splitting themselves into countless fine tendrils or capillaries, and several of these may compete legitimately for being the true

fons et origo

. Is it the stream that is farthest from the sea? Is it the stream that is at the highest altitude? Is it the stream with the greatest flow of water? There is little agreement on this point among either hydrologists or cartographers; and so explorers can make names for themselves even today by finding, or claiming to find, supposed new sources for well-known rivers.

The beginning of the Mekong, for example, was reportedly found by a Frenchman in 1995. But it may well be that another source, with an equally legitimate claim and yet equally difficult to verify, may be found by some other wanderer ten or fifty years hence. That, after all, is what happened with the Yangtze.

Until the closing years of the Ming dynasty, in the 1640s, the source waters of the Yangtze were thought to lie at the head of the Min Jiang, the big and (in those pre-pollution days) unexpectedly clear stream that joins the muddy Jinsha Jiang, the River of Golden Sand, at Yibin. The reason was simple: the wide and rushing Min was navigable for as much as 180 miles above Yibin, while the Jinsha, narrow, rocky and furrowed by turbulence, was closed off to boatmen by a line of mountains no more than 60 miles above town. The Min was by far the more important river for trade; logic suggested, therefore, that it had to be the origin-river.