The River at the Centre of the World (19 page)

Read The River at the Centre of the World Online

Authors: Simon Winchester

Tags: #China, #Yangtze River Region (China), #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #General, #Essays & Travelogues, #Travel, #Asia

I was awakened from this pleasant reverie by a Chinese soldier. He had a submachine-gun slung over his shoulder and was demanding to see my passport. We had reached the end of the Chin-huai stream, and the area ahead, on the far side of a crudely built brick wall, was controlled by the military. But only very informally: after I had shown my documents, I was waved through, and within minutes a group of sailors who were working stacking sandbags – for everyone was expecting the Yangtze to flood, as the radio had warned of excessively rapid snowmelt up near the headwaters, in Tibet – stopped and offered me tea. Their official task, they explained, was to guard a boat that was used by Party leaders whenever they came to Nanjing. Chairman Mao had used it many times on the river: perhaps I might like to see it?

I had to walk along a dangerous arrangement of planks balanced on breeze blocks, because all the normal entranceways to the dock were flooded: the river was rising very fast now, and ports upstream were reporting damage, warning that some dykes were in danger of breaking. Mao's pleasure palace is called the

Jiang Han

56 – the Han River No. 56 – though in Mao's time it had been called

The East Is Red Number One

. For nearly twenty years it had been his private yacht. He first used it when he swam in the Yangtze in 1956. He would do so again ten years later in an act that – as a sign of his rebellion against the wishes of the Party elders – essentially signalled the start of the Cultural Revolution.

It was not a pretty boat, and it was furnished poorly, though the stained sofas looked comfortably roomy. There was a lot of chrome and moulded plastic. The wood furnishings reminded me of those you would see on the set of a low-budget sixties television show – Dick Van Dyke's living room sprang to mind, or Mr Wilson's house in

Dennis the Menace

. A clock, broken, had sun-ray spikes. The main lounge had one of its walls entirely covered with the kind of wallpaper you used to be able to buy in cheap Scandinavian shops, a blown-up photograph of life-sized birch trees offering the illusion of being beside a forest. On another wall was a picture of Bora Bora.

In every room soldiers lay asleep in their underwear, though they got up and saluted groggily when I looked in. One of them, an officer, showed me the cabin where Fidel Castro had once stayed and said Kim Il Sung had been aboard many times. He then took me to a larger room occupied for a week by the Ceauşescus. I doubt if they had much fun. Mao's private stateroom, across the corridor, had a pair of giant armchairs and a huge bed, but little else. The kitchens were dirty, with bamboo buckets full of rice, and thermos flasks waiting to be filled with hot water for tea. Perhaps it had been more luxurious when Mao was its Great Helmsman: today it hardly looked suited for its role as China's royal yacht.

I had one final mission in Nanjing. I had left it until last in deference to what I thought were Lily's increasingly strident nationalist sympathies. Close to where the evening steamer was due to depart was, I had been told, a memorial marking the site of the city's – and perhaps of China's – greatest political humiliation. It had taken place in August 1842. Although this rather accelerated the pace of my backward progress through history (so far in voyaging from Shanghai I had passed back sixty years, to 1937, which was roughly what I had expected), I had always known that this was going to happen: the historical aspect of this journey was only approximate, at best. And while I felt reasonably comfortable in paying only slight attention here to the Nanking Incident of 1927, and the Taiping Rebellion of the 1860s, it was impossible to ignore either the Japanese assault of 1937 or, as in this last excursion, the signing of the Treaty of Nanking in 1842. I told Lily this is what I wanted to see. ‘Oh my God,’ she wailed. ‘Your bloody British Empire again!’

The memorial was tucked away off a side street, not far from the old British Embassy (which is now a seedy two-star hotel and from where a local businessman was trying to sell debentures in a new golf club, at $20,000 apiece). It is in a tiny temple known as the Jing Hui Shi, which was made famous five centuries before when Cheng Ho, the country's most famous explorer, stayed there before he took off on his famous sailing trip to Mogadishu.

*

It is now called simply the Nanjing Treaty Museum, and it is looked after by an elderly lady named Mrs Chen.

‘How nice to see a foreigner here,’ she said chirpily when I walked in, banging my head on the low doorway. ‘Even the British are welcome here now. This is all just – history.’ She took two yuan from me, and made as if to add some further comment, but whispered that she would say it later. She picked up the telephone and spoke in a low voice to someone on the other end.

The treaty was signed on 29 August 1842, in the captain's cabin on the man-of-war HMS

Cornwallis

, moored a quarter of a mile offshore. It had come about after British soldiers, fresh from a military success in Zhenjiang, from where we had just come, had established themselves in a commanding position outside the Nanjing city walls. That was 5 August: the local Qing dynasty leadership – charged with plenipotentiary permissions from the Emperor Daoguang's court in Beijing – agreed to negotiate. A seasoned diplomat named Sir Henry Pottinger had been appointed by Lord Palmerston to negotiate for the British and bring to an end the two years of tiresome skirmishing that have since been dignified as the First Opium War. (His predecessor, Charles Elliot, had been summarily sacked by Palmerston for a variety of supposed offences – one being his choice of settling in Hong Kong, which the British prime minister described scathingly, and with a stunning lack of prescience, as merely ‘a barren island with hardly a house upon it’.)

At the beginning of the second week of August, Sir Henry Pottinger entered the little Jing Hui temple and seated himself at a hastily set-up conference table. On the other side, resplendent in his purple robes and scarlet-buttoned cap, was a Manchu mandarin named Qiyang. For two weeks these two, and their attendant advisers and translators, worked out an agreement that would change China's history for all time. The resulting treaty would force the Celestials to open themselves up to commerce with the barbarians – a term that was formally used in this treaty, and would be for another ten years. It would also begin the dismemberment of the Chinese nation – and spark the wider ambitions of the still slumbering island-nation nearby.

The Treaty's full text, written in elegant calligraphy, can be read on one of the walls of the small museum. Any visiting Chinese – and there are not many visitors at all, so tiny and tucked away is the place (I found it odd that they keep it open at all) – may read all of the twelve clauses, and realize how humiliating it must have been then, and how eager the Chinese are to rid themselves of the humiliation today.

The second clause was the most unpalatable of all. ‘The island of Hong Kong shall be possessed in perpetuity by Her Majesty Queen Victoria and her successors, and shall be ruled as they see fit.’ There were other matters: five treaty ports to be opened, $21 million to be paid in compensation for burned opium and other indignities,

*

the establishment of a customs service with fair duties levied on goods, the formal abandonment of phrases like ‘petition' and ‘beg' in all further communications between the two courts. But they were as nothing compared to the savagery of having to give up an island, part of the most ancient empire on earth. It was a bitter pill for Daoguang to swallow then. Over subsequent years other morsels fell to other nations – Manchuria and Liaoning and Shandong and even the Summer Palace in Beijing itself, and the bitterness and isolation of China increased, and she retreated to her lonely contemplation of nobler times of old, and of her hopes of nobler times to come.

Mrs Chen came up to us, telling Lily to stop tutting and clicking her tongue. ‘It is not this man's fault,’ she said, kindly, looking at me. ‘Besides –’ only she was interrupted by a bespectacled, cheerful-looking old man who introduced himself as Professor Wang, director of the Nanjing Relics Bureau.

‘Besides, Mrs Chen,’ he said, drawing himself up for a lecture, ‘all this humiliation is about to be ended now – isn't it? Now we have almost everything back. Manchuria is ours again. Shandong was taken back from the Germans. The Russians were kicked out. So were the Japanese – the hateful Japanese. The Portuguese are leaving Macau.

‘Now all that remains are you people, the British. And very soon now you will go. Your Mrs Thatcher knew that she could not defend the Pottinger treaty. She knew that Hong Kong could not be held for ever. So you are having to give up and go home.

‘Once you have done that we will have all of China back. Maybe Taiwan, too. It will be a glorious day for us. Then the treaty signed here will just be a relic – of no importance. People will not forget. But they will never let it happen again.’

Professor Wang let that sink in, then smiled broadly at Lily, sighed with pleased relief and suggested that Mrs Chen pour us all cups of tea. ‘Now we must be friends. But equal friends. Not like before. We Chinese are at least the equal of you now, don't you agree? At the very least, equal.’

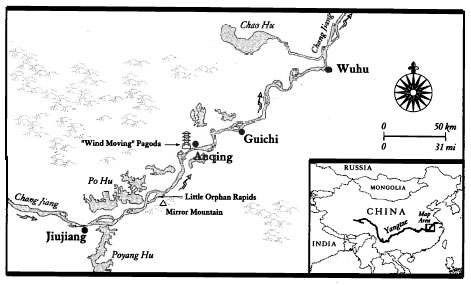

We waited in the gathering gloom for our 9 p.m. boat to Jiujiang, and other points upstream. Kathleen, an American woman I knew vaguely who taught at one of the universities in Nanjing, had come to see us off. She was from Connecticut and was in love with China, didn't much want to go home. She taught English to a class of about forty students. That day they had been reading

Tess of the D'Urbervilles.

I had been telling her of the conversation with Professor Wang, and I remarked that he – like many Chinese these days – seemed to have been much more candid with me, much more forceful and direct than used to be the case. Perhaps, I said, he was displaying something of the country's new self-confidence, a new belief in itself.

‘I'm not so sure,’ she said. Some things were still only discussed behind veils, she went on, were talked about only with great embarrassment. Sex, for instance.

‘Only today it happened. I have a student called Nancy, twenty-one, beautiful, perfect English. I had asked her to précis the book. She got to the bit where Alec D'Urberville rapes Tess when she is sleeping in the wood. The rape that led to the child, near the start of the story. Well, Nancy was telling the class how Alec had taken her for a ride, how they had gotten lost, how they had to stop in the wood.

‘Nancy paused in the story here. “And then?” I asked. She blushed. She didn't want to say it. And then finally she came out with it.

“‘Alec,” she said, “was then

very rude to her

.”

‘I was amazed, for a moment. Then I asked her what she meant – rude? But she wouldn't say, and just hung her head. That wasn't rude that was rape! I yelled. I suppose I was a bit too American about it – trying to force the issue. But she wouldn't talk about it, and nor would anyone else in the class.’

Lily said: ‘That's Nanjing for you – very conservative place. Very conservative people.’

‘I'll say,’ said Kathleen. ‘It was even worse when I started talking about homosexuality. I thought I'd go for broke. I told them it exists everywhere – in China as well as everywhere else. I told them there were gay prostitutes on the pedestrian bridge near the Shin Jie gate, near your hotel. They just wouldn't believe it.

‘They said that there are hardly any homosexuals in China, and that I wasn't to import my ideas about them, please.’

Lily stood up. ‘We must get on board now,’ she said. Her mood, changeable at the best of times, had suddenly hardened. I was afraid I knew what was coming.

‘The students are right, you know,’ she said. ‘There really is no homosexuality here – except for some ill people. It is a disease, a mental disease. Something that can be cured. It is quite disgusting. Americans allow it. We do not. I can't blame them for not wanting to talk about it.

‘But Tess and the rape. That's different. That's just Nanjing people. Nancy was a very typical girl. People in Shanghai wouldn't feel the same. Rape is a very sensitive subject here. I am sure you both know that.’

The boat's siren sounded. Thanks be, I muttered to myself. The last thing I wanted to be caught in the midst of was a fight between a stridently and vocally modern American woman and my tough-as-nails companion.

The Clash of Two Civilizations

had nothing on a full-blown argument between these two. I said my farewells to Kathleen, who rolled her eyes heavenward. Lily and I joined the throng, feeding ourselves into the huge crush of people at the gangplank like a slab of beef going into a mincer.

‘Soldiers go first!’ scolded a woman guard, harshly. That was always the way: Let the Soldiers Pass First, said a notice board. They Make Great Sacrifices for Our Nation.

6

Rising Waters

The last traces of the evening sun were glimmering from behind the purple clouds of factory smoke as the

Jiang Han 18

edged gingerly out into the swollen stream. A long freight train rumbled over the bridge behind, its wagons heaped high with coal for plants and smelters on the north bank. The ferry from Pukou, its lower decks crammed with passengers and bicycles, was sweeping around the harbour buoy. An old man in a string vest standing beside me on the

Jiang Han's

second deck was pissing happily over the side of the boat; as he buttoned the fly on his khaki shorts so he spat down into the river, thirty feet below, for good measure. The clock on the Nanjing Ship Terminal then struck – or clanked – a tinny and discordant nine times: we were leaving exactly on schedule, with just over six hundred passengers jammed among the hot ironwork below.

We had managed to secure a cabin just below the navigation bridge. It had cost us: the usual double price that foreigners are invariably obliged to pay, together with a twenty-yuan bribe. But the alternatives had been less than enticing: either a huge dormitory, its sizzling floors awash with dubious-looking fluids and crammed with a jolting mass of shouting humanity, or a third-class bunkhouse in which twelve beds – four tiers of three – provided some measure of serenity and comfort. But for only twenty dollars one could travel second-class – first-class still being an officially forbidden phrase – with a lockable door, a working fan, and beds with curtains. The journey was to take twenty-five hours: at that price comfort seemed very good value.

‘More like thirty hours, this trip,’ said Captain Wu De Yin, when I went up to the bridge. ‘The flooding this year seems very bad. The stream is quite fast. Downstream we came along like a rocket. But upstream we are having to fight every inch of the way.’

Captain Wu had been on the Yangtze since he was eleven – more than forty years. He had once worked on the Kunlun, the boat that was now used to take tourists along the Yangtze and which was mistakenly said by its American charterers to have been used by Chairman Mao. ‘Zhou Enlai, yes,’ he said. ‘Mao, never, I'm sad to say.’ He pointed respectfully to a small photograph of Mao that bobbed on a string from a bulkhead pipe, a talisman. All long-distance travellers in China had them, Mao or Zhou and sometimes both, together with a length of red cloth that fluttered in the wind: they doubled as Saint Christophers and as a visible sign of faith in the Party.

Captain Wu had left the

Kunlun

with honours ten years before, and for the last decade had worked on the scheduled passenger boats like ours, shuttling between Nanjing and Wuhan. This is what one might call the upper reach of the Lower Yangtze – and journeying in these waters always sorely tried his nerves.

‘Everyone imagines the Yangtze is only difficult in the Gorges,’ he said, lighting a cigarette. ‘But this river – pah! – it is always difficult. Always. It changes every day, every hour. One moment there is clear water and then – pah! – there is a whirlpool that will suck you in and turn you round and before you know it, you're heading for a rock, or a cliff.

‘You have to treat it like your enemy. It is a real battle, going up this river. I will show you in the morning. But even now you can hear it – just listen.’

And I cocked an ear to hear something above the deep-throated roaring of the engines, and below the cries of a legion of off-key singers in a crew cabin behind us. After a few seconds there was a sort of iron hiccup in the rhythm of the diesels, a squeal of distant chains, and the boat seemed to lurch slightly from the port side. I staggered. The captain did not. For a moment or two longer the boat resumed her smooth progress, and then there came another battering, this time from starboard. There was a second squawk of industrial pain from below, another sound of tortured metal, another lurch.

‘See what I mean? All you can see ahead is the night. It looks quite calm. But below us the river is doing strange things. I can never say I know it. I know the ports, the destinations. I know the bridges, and all the lights. But the water – wah! – it is a strange beast. I should get paid more than I do!’ He said he was paid about 6000 yuan a month, around £450.

Before turning in I stood on the bridge wing, gazing out into the inky blackness. It was a warm and humid late spring night, and rivulets of condensation ran down the steel plates. In the distance there was the glow of factory furnaces, each a silent indication of China's strength. But from down below came an unsteady gurgling roar as the river coursed by our hull – a reminder that the river was stronger still and, as all who live along her banks know full well, that she would be able to snuff out all those distant fires and a great deal else besides, with no more than a summertime shrug of her giant shoulders.

This stretch of the river suffers terribly from floods. Later on I would find out that what was at that moment swirling below our hull was reported to be a memorably bad flood: it was said that 1500 people were killed and hundreds of millions more were ‘affected’. Patriotic television films would show heroic soldiers gallantly fighting to secure dykes and dams along thousands of miles of brimming streams. But however destructive the 1995 floods, they were as mere wettings compared with what the Chinese believe to have been one of the worst natural calamities of all time: the Central China Flood of 1931. The wild and wayward Yangtze, as usual, was to blame.

Except that the blame can be apportioned much more fundamentally than this. China is a country that is doubly and uniquely cursed, both by her climate and her topography.

Her cross-section, for example, is dramatically unlike any other on earth. China's western side is universally high – an immense mélange of contorted geologies that involve the Himalayas, the Tibetan Plateau, and the great mountain ranges of Sichuan, Yunnan and Gansu. Her eastern side, on the other hand, is flat and alluvial and slides muddily and morosely down into the sea. The country in between is far from a smoothly inclined plane, of course, but the difference in altitude between her western provinces and the sea is so vast – involving four and a half miles of vertical drop – and the trend of the slope so unremitting that anything which falls onto her western side, be it snow, hail, torrential rain or the slow grey drizzle of a Wuhan autumn afternoon, will roll naturally and inevitably down to the east.

Her two greatest rivers, the Yellow River and the Yangtze, flow in precisely that direction – west to east. They take this runoff from the high Himalayas and the other ranges and then, capturing river after river after river along the way – all of which do just the same, scouring their source mountains for every drop of water they can find – they cascade the entire collected rainfall from tens of thousands of square and high-altitude miles down into the earth-stained waters of the East China Sea.

But the configuration of China's surface is not the only factor. It is eccentric, certainly, like one half of a temple roof. Nonetheless, it could have offered the country a hydraulically manageable situation, were it not for four additional curses.

The first is that China receives a very great deal of rain each year – far more, per square mile, than Europe or the Americas, and, in places, as much as the record-holding villages of Assam. Second, nearly all of this precipitation falls in the topographically chaotic west and the south of the country – the principal reason, as it happens, why rice is the crop of choice grown in the wet warm south, and wheat the staple of the dry and cool north. (The dividing line, the so-called wheat–rice line, almost precisely parallels the track of the Yangtze.)

Third, this substantial and geographically concentrated rainfall is intensely seasonal – the summer monsoon dominates southwestern China's weather system, just as it dominates the northern part of the India against which China abuts. This is a very odd combination: in very few regions around the world is rain concentrated both by place

and

by time. It is not in India, for instance. It is not in the Amazon valley. Nor is it anywhere in Europe. But in China, savagely, more or less all of it falls in one place, and more or less all of it falls in one four-month period, between June and September.

Fourth, and as if the other reasons were not enough, the rain falls just when the summer sun begins warming things up things that include, crucially, the snows and glaciers of China's western mountains. These start to melt, and to produce their own torrents of eastbound water, at exactly the time the rains come.

The coincidence of these four factors – each of which, like St John's Four Horsemen, is an agent of potential destruction – produces results that are often quite literally apocalyptic. Every summer and all of a sudden, gigantic quantities of water begin to course down each of the tributary streams of China's two main river systems. Some comes from the melting ice and snow. Some comes from the torrential monsoonal rains. But all goes eventually to the same two places.

In the north of the country the Huang He, the Yellow River, swells rapidly and enormously. It collects additional waters from its two main feeder streams, and it wrenches millions more tons of loess out of China's heartland and carries them swiftly out to the delta, and the sea.

*

Not for nothing is this river known colloquially as China's Sorrow, or The Unmanageable.

But the Yellow River's history of flooding, while spectacular, has rarely been as catastrophic as the Yangtze's. The Yangtze is nearly a sixth as long again as the Yellow, and rages through hundreds more miles of mountainous and well-watered land. It has in addition very many more tributaries – about seven hundred in total, and among them are formidable rivers like the Yalong, the Min, the Jialing, the Han Shui, the Wu and the Yuan. Each of these deserves to be ranked among the world's biggest rivers itself, but in this context they are mere contributors to the Yangtze and to its huge engorgement.

Furthermore, unlike the Yellow River, the Yangtze flows through a part of China that is itself rained upon during the monsoon season – meaning that to whatever mass of waters it has collected from the hills and the tributaries, still more is added from the rain that simply falls upon the river's surface as it slides languidly through the lower stages.

The results are invariably stupendous, occasionally disastrous and, more often than seems fair, catastrophic. In 1871, the river at one point rose – and quite suddenly – by no less than 275 feet. A little above where I was sailing this night, places exist where the average summertime rise is 70 feet, year after year; and painted on the rocky walls and on cliffs and poles and riverside buildings all along the way are the ragged white numerals - once in feet, now in metres – showing the possible range of the water. At Jiujiang, which we were due to reach after a day's hard sailing, there was said to be a plaque recording the level on the fateful 19 August 1931: the river rose 53 feet, 7 inches above normal, and inundated everything for miles around.

During that summer, in addition to all the normal mountain monsoons and snowmelts, calamitous rains fell along the entire length of the middle and Lower Yangtze. Storms raged all over these very lowlands through which I was now steaming – lowlands that begin at the foot of a mountain range five hundred miles ahead and extend to the ocean that now lay three hundred miles behind. This extraordinary amount of water was dumped into a river that had already been swollen massively by the melting of the Tibetan snowfields and was, moreover, about to get huge shock infusions of storm water from its mightiest tributaries.

The results were that the Yangtze, at precisely the point where I was now rumbling through the night, first rose to 30 feet above its present level and then, no fewer than six times in quick succession, was jolted by great storm bores as the new tributary waters kicked in.

The tributary bores are no joke. In a bad-flood year a grotesquely swollen Min River, for example, discharges itself into the Yangtze and produces a ten-foot tidal wave, which sweeps down and along the river for days. Another bloated river like the Jialing disgorges its water in the same way but a few days later, or earlier, depending on the weather near its own source, this causes another tidal wave to rush out into the great river – and so on and so on. Before long an aerial view of the Yangtze would show it overflowing its banks for hundreds of miles, and then those broken banks and inundated villages and towns being buffeted by successive new water pulses, each a few days or so apart. In 1931 there was no slow inundation: it was rapid flooding, followed by episodes of total immersion, then a brief relief, then total immersion once again, five more times.

The consequences of what the history books now record as the Central China Flood were staggering, the figures numbing and barely credible. More than 140,000 people drowned. Twenty-eight million people were affected – forty million by some estimates. Seventy thousand square miles of central China were submerged – as much land area as in all of New York state, New Jersey and Connecticut combined, or all of England and most of Scotland. Twelve million people had to migrate or leave their ruined homes – twice that number, according to the more doom-laden reports. Two billion dollars in losses – and those are 1931 figures, when the average family earnings in China were just a fistful of cents in copper cash – were directly attributable to the flooding. Some streets in cities like Wuhan, two days sailing away from me this night, were under nine feet of water, others under twenty feet. The city remained awash for four months. Fields nearby, not protected by dykes, were thirty feet under. Nanjing was under water for six weeks.