The River at the Centre of the World (16 page)

Read The River at the Centre of the World Online

Authors: Simon Winchester

Tags: #China, #Yangtze River Region (China), #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #General, #Essays & Travelogues, #Travel, #Asia

It was in part because I found both the camels and the canal so depressing that I decided to leave Yangzhou to its infestation of tourists. Back on the muddy flats of the riverbank I found a junk whose owner was willing to sail us back across the river for a few jiao, and within half an hour of bumping over the greyish waves Lily and I were happily back on the wet stone steps of the Zhenjiang dock. There was a sudden shout of recognition: it was the fisherman who had been showing us his collection of rolling hooks earlier in the day. He had been working all day mending a net, and since he looked cold and tired I suggested that he come and have a bottle of beer at a local bar. He puffed on his bamboo pipe, and showed Lily how to do the same. We ended up the best of temporary friends, and he gave me the name of a friend he said I should look up in Nanjing: it was another fisherman, just in case I wanted more stories about dolphins.

There was one small pilgrimage I had to make before I left Zhenjiang. At the turn of the century Mr and Mrs Absalom Sydenstricker, Presbyterian missionaries from West Virginia, had brought up a child there, a child who later studied in Shanghai and Lynchburg, Virginia, and went on to write novels under the name John Hedges.

But John was in fact a girl-child, named Pearl, who later married another missionary named John Buck; and it was under the name Pearl S. Buck that she wrote most famously, and under which name she won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1938. The woman who wrote

The Good Earth

, the creator of Wang Lung and his slave-wife and their rise and fall through the vicissitudes of famine and locusts and war and concubinage, lived for fifteen formative years in a house in Zhenjiang. It is now a radio factory, and since Pearl Buck has been restored to a tepid kind of official favour – she was officially prevented from coming to China in 1972 – it stands open to the public, occasionally.

No one knew where it was, naturally. I approached a dozen people and gave them Pearl Buck's Chinese name, or the Chinese title of her best-known book, and I still got blank looks on all sides – a reflection, no doubt, of my lamentable pronunciation. Lily then asked where the Zhenjiang Number One Radio Factory was, got directions in an instant, and we walked up another cobbled street to where it sat on a hilltop – and beside the plant itself was a small two-storey house behind a high barbed-wire fence: The Home of Pearl S. Buck, said a wooden plaque, Winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The house was shut, naturally. But a woman lived there, and through the wire I managed to persuade her to open both the gate and the front door to the house. ‘But' – she spluttered, and I knew what was coming next – ‘her private rooms are locked and' – and both Lily and I joined in the mantra chorus that inevitably followed, as burp follows noodles – ‘

the man with the key is not here

.’

So I used my Citibank card, which had previously been so useful in Shanghai for showing me my balance on the Bund. I twisted and turned it in the lock, and within twenty seconds was in the lady's bedroom. Pearl Buck slept hard, on a plain mahogany bed, and she kept her clothes in a plain mahogany cupboard. Everything about her part of the house, indeed, was plain and unadorned, with a Shakerite austerity. But then there was a room devoted to, of all places, Tempe, Arizona, with which Zhenjiang has lately become affiliated, as a sister city. So there was a Kachina doll, a basketball signed by some of Tempe's tallest, and countless photographs of Tempe worthies shaking hands with smiling officials from Zhenjiang while paying homage, as I did, to the city's best-known daughter. There was no connection at all between Miss Buck and the city of Tempe: but the Chinese, still officially irritated at the writer for her implacable anti-communism, seemingly thought it quite reasonable to herd all western tributaries, whether they came from Arizona or the Appalachians, into the same building. Some say that the house was actually never the Sydenstrickers' at all, and that the authorities are playing a joke on Pearl Buck's memory, on the Arizonans and on us today. To the Chinese, it must not be forgotten, we are all alike, and can well afford to be the butt of their little amusements.

I pulled her bedroom door behind me until it locked, gave the old woman five yuan to compensate for her initial shock at and later complicity in my housebreaking, and walked away from the radio factory, Pearl Buck's home or not. I flagged down a taxi, piled in our bags and asked him to take us to Nanjing.

It turned out to be a slightly eccentric journey, though nothing particularly unusual for the adventurous universe in which Chinese taxicabs like to operate. In this case the man offered to give us the ride to Nanjing at half price if we in return would agree to let him cross the Yangtze once again to pick up one of his relations, an elderly man who lived on the outskirts of Yangzhou. This meant we would have to board the car ferry one more time, and that we would have to approach Nanjing by driving on the river's north shore, not the south. But all this seemed of little moment, and I readily agreed. The driver was very happy. I rather liked the little car ferry, anyway, and I stood happily in a thin evening drizzle, watching the lights of Zhenjiang prick on in the gathering gloom.

It seemed that I was drawing away from the city and from one very small enigma – the minor mystery of what exactly was the long-forgotten piece of Royal Naval hardware that lay behind the bushes in the consulate garden. Later that night, once I had taken a long hot shower in the hotel in Nanjing, I found with some gratitude that I was leaving behind something else: the pervasive sharp-sour smell of the medal-winning, first-class, internationally renowned and copiously produced Zhenjiang Brown Rice Vinegar.

5

City of Victims

On the outskirts of Nanjing I knocked a young woman off her bicycle. She was wearing a long white linen skirt and she fell with the slow grace of a ballerina, managing perfectly to preserve her dignity. It was all, without a doubt, my fault.

Moments before our driver had been pulled over by the police. The routine that ensued was to become a familiar one: an officer with a flag leaps from behind a bush, waves us to a halt, mentions some alleged infraction; the driver is persuaded to cross the road and discuss matters with a group of well-fed-looking colleague-officers, a not insubstantial sum in folding money changes hands, the first policeman is told to return the licence, drop his red flag and let us proceed, whereupon he then wedges himself behind the bush once again. Thus does traffic in China keep moving smoothly; thus does the small corps of car owners pay a reasonable additional tax for the privilege; and thus do policemen lie abed happily each night.

During these early days of my own journey I was innocent enough and arrogant enough to think I might be able to help – or to object or argue – when a situation like this presented itself. In this instance, Lily warned me not to try, saying sternly that my presence would only complicate matters. She bade me stay in the car. Ignoring her advice I opened the right-side back door to get out – and very nearly killed the young woman.

There was a sudden cry, a scraping sound like fingernails on a blackboard, and a sickening crunch. The door was slammed rudely and forcefully back on me and then I watched in appalled silence the slow-motion image of a young woman going down with her skittering bicycle, like the last moments of a dying swan. Her front wheel headed downward from the levee on which we were parked, the other wheel swerved back into the roadway, and between them fell the woman, sinking slowly onto the gravel and the mud. She turned her head around fast so that her long mane of black hair whipped around behind her, and she glared at me – a handsome face that looked at once perplexed that anyone could not know that Chinese cyclists rode close to cars and that is how it was and always had been and how foolish of anyone to open a door without looking, and angry that she was about to be hurt, perhaps, and also that in front of a carful of strangers she was going to fall over and tumble and show her legs, and worse, and lose her dignity and face and the elegant comeliness with which she evidently tried to ride her bicycle every day.

Gravity did its powerful work, and I thought the woman would steadily and inevitably succumb. But instead she fought for all she was worth, and as she fell so her legs twisted this way and that, and her arms did the same, and she stared ahead and around with such concentration that, by the kind of miracle no foreigner could ever manage, she did eventually stop the great black confection of iron and rubber that I recognized as a Flying Pigeon brand bicycle from falling any more, and she managed to halt its forward progress and its downward progress and its tipping and skidding as well, and she managed to stop herself falling too – she just sank, caught her balance and her breath and her dignity, and stopped, in a crumpled mass of white linen, lying between two upright wheels and in a cloud of dust.

With a sudden weary sag of her shoulders she remounted the saddle, looked back at me in silent fury once more, straightened her wheels, shook her head in defiance of that gravity and momentum and the baleful influence of the foreigner who had initiated all this, and shakily, nervously, bumpily and then with ever-growing confidence she resumed her ride, joining in with the uncaring rows of other cyclists and merging among them, anonymous and dignified once again. She gave me one last look – a beautiful face framed by a marvel of hair, her white blouse slightly off one shoulder but still crisp and fresh, her long white skirt a little crumpled and with a small smudge of dust down one side. She looked glorious, I thought, newly arisen from what could have been the wreckage of her day, and riding serenely off into the afternoon sun.

Rising from wreckage of one kind and another has been a perennial occupation for the city of Nanjing. Very few places in China have soared and plummeted with such fantastic and tragic recklessness. The city was the glorious capital of some dynasties, and then remaindered as a dusty and provincial backwater for others. There was, as in many Chinese cities of long history, at least one of those tragedies that scholars later term an ‘incident’: this came in 1927, when Nationalist troops killed seven foreigners, and a force of foreign gunboats sent to retaliate shelled and killed twice as many Chinese. But there had been more terrible tragedies too: during late Qing times, for example – for the eleven years between March 1853 and July 1864 – the city became the headquarters of a notorious sect of power-hungry fanatics, the Taipings, whose resistance was eventually destroyed (along with most of the city) after a siege partly staged by a foreign-led mercenary army, and whose leader was driven to suicide (it is said) by swallowing gold.

*

This most traumatic of events was sandwiched between two other humiliations: ten years before the arrival of the Taiping rebels, the city had been forced to bow low before one group of barbarians, the British; and seventy years after the Taipings, Nanjing became an epicentre of mayhem and cruelty at the hands of another group, the Japanese.

It is a city that, more than almost any other in China, has fully deserved the doleful and all-too-common description that you will read in all Chinese history books, a sentence that appears in one guise or other, referring to some such place in some such time at the hands of some such madness: ‘Its population was greatly reduced, its trade destroyed, and many of its beautiful, historic buildings and part of its walls, reduced to ruins.’ Nanjing has had, in other words, a horribly chequered past.

And yet on the surface you would never know it. Her present is blandly prosperous. Her image is relentlessly upbeat. It seems as though under the Communists the city of Nanjing has been urged, cajoled,

made

to rise from all that has gone before. Perhaps because of her past glories she has had money spent on her, she has come in for the caring attention of the central government, and has been persuaded to shake herself free of the more wretched side of her history. And she has gone along with the country's perceived wishes: she has washed off the dust and grime and, even if she is slightly crumpled from all of her trials, she looks well enough now, and quite presentable. Which is what the country seems to want for its most shabbily treated town.

For whenever I told a Chinese that I was planning to go up the Yangtze and stop a while at Nanjing, they would invariably say what they would never say if I admitted I was off to somewhere more pedestrian, like Harbin or Changsha or Canton: ‘Oh, really? Nanjing! How nice! How lucky you are!’ one man said. ‘Lovely city!’ said another. One elderly man in New York became dreamy-eyed and hinted at romance, muttering a nostalgic formula: ‘The flower boats! Taking your ease under the shade of a weeping willow, listening to a pretty little singsong girl… ah, that was the life… What a fine, fine place!’ This old man knew what had happened to the city through the years; but he seemed to be caught up like everyone else in the earnestness with which the rest of China seems to be trying to reinvent Nanjing. ‘One of the most interesting cities in our country – truly,’ said Lily. ‘All of us are very proud of Nanjing – of the way her people have risen above all their sufferings.’

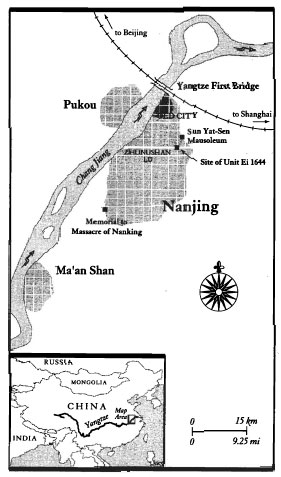

That evening as we drove in from Yangzhou – having passed the still angry cyclist – the first view was the one that seemed most apt, a panorama that showed off Nanjing's newness and her determined effort to be modern. We crossed the river not by ferry, as we had been forced to do at Zhenjiang, but on a vast bridge – the bridge that is closest to the river mouth, and one of the longest, heaviest, ugliest, most graceless triumphs of engineering built to cross a river anywhere in the world. It has a magnificence to it, though: it is solid and imperturbable looking, lined with ranks of the five-bulbed egg-lamps that have been a ubiquitous feature of the Chinese landscape since 1949 – and which were probably made in the first factory in the first Chinese soviet ever created. The bridge has four buff concrete towers, two at each end, with triple-flamed beacons on top; and on the landward side of each of these, two collections of heroic statues, one in memory of those who built the bridge, the other in honour of all of those who harbour socialist sympathies around the world.

Until I read the inscription I was rather puzzled by this second statue. It seemed a little odd to have the entrance to Nanjing memorialized by a very white cement statue of a group of people led by an obviously very black man. He was looking joyous and defiant and – given the hearty (although heartily denied) Chinese dislike for their black brethren – very irrelevant. Or certainly discordant. There was a woman running a food stall on the other side of the road: I asked her what she thought.

‘Of what?’ she grunted. ‘That statue? Wonderful, I think.’ But what, I pressed, of having a black man leading the group? She squinted up at it, disbelief written over her face.

‘Black? Black? My word – yes! I suppose he is. Would you believe I never noticed. Working on this very spot night and day for the last eight years. Eight years! I know those statues like my own bed. It never occurred to me that man might be black. Of course I can see he is now. He couldn't be anything else.’

And she wrinkled her nose, as if there was a nasty smell in the air. Which, this being Nanjing – producer of lead, zinc, dolomite, iron, televisions, cars, clocks, watches and, to judge from the huge flames I could see gushing up from refinery towers all around, petroleum products in abundance – there probably was. Time was when Nanjing was the world's great producer of a soft silk called pongee: this, not an industry known for its smell, has now all but vanished.

Building the bridge had been extraordinarily difficult. The Yangtze is for most of its length an almost impossible river for an engineer to deal with – it is very fast, very deep, it is given to eccentric turbulences and cruel unpredictability, and it rises and falls to a degree that most bridge foundations would find fatally punishing. In Nanjing, the range of water levels is particularly complicated, for not only is the river narrow enough for the outflow to vary hugely with the seasons, but it is also close enough to the sea for the effects of tides to be noticed still. (They say you can feel these effects as far away as Datong, a full 350 miles upstream, though the ocean's practical effects on shipping are of no real importance above Wuhu, 289 miles from the ocean. And it is here at Nanjing, 50 miles below Wuhu, where the river is said to start being properly tidal.)

The Yangtze at Nanjing is on average eighteen feet higher in July than it is in January; and at high tide it is nearly four feet higher than that – so the buttresses and columns designed to support the 20,000-foot-long, twin-deck, four-lane-roadway-above-two-track-railway

*

bridge have to withstand the river's current, the sea's tides, the estuary's bores and a range in water height that is unknown on any river elsewhere on the planet.

The problem was first approached in 1958, when the Chinese realized that they must end the nonsense and delay of having to use ferryboats to get their railway passengers and freight across the great river. The Russians, masters of river bridging at the time, were asked for advice, and then assistance – they eventually agreed to provide a design, as well as technical help and the right kind of steel. But shortly thereafter political relations with Moscow went into a tailspin and their engineers were hauled back home – insisting anyway that no bridge could be constructed over so wide and wayward a river for at least another three hundred miles upstream.

They hadn't realized just who they were talking to. The China of the late 1950s was a country intoxicated with the madness of her Great Leap Forward, a people suffused with a barely rational pride and determination, and a nation whose technical institutes were filled with engineers who insisted they could manage the building of this bridge, however difficult, quite alone. It took them eight years, and it required the total reorganization of the Chinese steel industry to provide the necessary bars and girders. But they did it. At the end of 1968, when the whole world was in the midst of revolutionary ferment and when China was starting her own, the Yangtze First Bridge was formally and proudly opened. The Chinese way, it must have seemed back then, was capable of achieving almost anything: the bridge may be ugly and graceless, but it works, and thus far it has shown few signs that it is about to fall down.

I had the address of one man in Nanjing, an Italian who worked for a truck-assembly joint venture and who had lived in the same hotel in fact the same hotel room – for the previous eight years. I telephoned him. ‘Come immediately,

prontissimo

!’ he demanded, and he gave me the address of the Jinling Hotel, thirty-six storeys, locally owned and, by all standards, a five-star establishment. It was in the centre of town, at the junction of four avenues each named Zhong Shan (North, South and so on), in honour of Sun Yat-sen.