The Road to Berlin (52 page)

Read The Road to Berlin Online

Authors: John Erickson

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Former Soviet Republics, #Military, #World War II

On 23 July the Germans put in a heavy counter-attack against Batov’s right flank, ‘moving from north and south with strong tank support and crashing into the area of 65th Army forward

HQ

. Batov’s signal to Rokossovskii was interrupted by the appearance of German tanks and left hanging in the air as shells burst on the badly camouflaged signals centre. From Front

HQ

Rokossovskii signalled: ‘Where is Batov?’ Receiving no reply, Rokossovskii sent fighter planes to scour the area between Kleshchela and Cheremkha; that evening Rokossovskii and Zhukov arrived at 65th Army

HQ

, where Zhukov showed himself less impatient and even offered reinforcement to eliminate the German breakthrough into Batov’s corps. This German attack slowed the Soviet advance but could not prevent Brest-Litovsk from being closed off when, on 27 July, 28th Army and 70th Army (Lt.-Gen. V.S. Popov’s formation from the left flank) lined up on the eastern bank of the western Bug north-west of Brest-Litovsk. Eight German divisions, the remnants of the German Second Army and Ninth Army, hung on to Brest-Litovsk for as long as possible, the garrison reinforced with tanks moved up from Warsaw. Rokossovskii had undertaken a giant encircling movement to cut all communications between Brest-Litovsk, Bialystok and Warsaw, using his right and left flanks, but in Brest-Litovsk itself Soviet units had to beat down strong German resistance before the town, with all its road and rail links, fell on 28 July. The gap between the left wing of 1st Belorussian Front, 2nd Tank Army and 8th Guards driving north-west to the Vistula and in the direction of Warsaw, and the forces clustered about Brest-Litovsk, was now considerable.

As Rokossovskii opened the battle for Lublin, Koniev ended the encirclement battle west of Brody: on the evening of 22 July more than 30,000 German troops had been killed and 17,000 made prisoner. Once the liquidation of the pocket was complete, Soviet divisions were free for operations directed against Lvov itself, where the Soviet assault force made only slow progress. Marshal Koniev hoped to seize Lvov off the march with his armoured units, before German

reinforcement could move up from Stanislav; on 18 July the situation seemed favourable for a

coup de main

, with 3rd Guards Tank Army and 13th Army not more than twenty miles from the city, and 10th Tank Corps (4th Tank Army) already at Olshanitsa to the south-east. Koniev therefore prepared to outflank the city from the north and south, then seize it by 20 July.

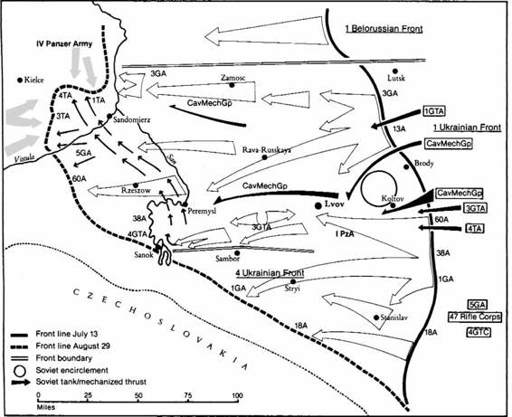

Map 9

Lvov–Sandomierz operations, July–August 1944

That this did not succeed Marshal Koniev attributed to the errors committed by Rybalko (though admitting the factor of the heavy rain, which slowed down 3rd Guards Tank Army’s artillery and supplies). Rybalko took the shortest route, the Brasnoe-Lvov road, only to land his tanks in the peat bogs north-east of the city. All hope of manoeuvring the tank army due west of the city was lost, and 3rd Guards was tied up in heavy fighting close to Lvov. By 21 July three German divisions moved up from Stanislav and it needed more than a tank army to shift them. The Front command therefore decided to bring 3rd Guards

Tank Army round to the west and northwest, move Lelyushenko’s 4th tank on from the south and advance Kurochkin’s 60th Army to attack from the east, while Moskalenko’s 38th Army would drive from Peremysl to the southern outskirts of Lvov. Radio contact had been lost with Rybalko, but his orders to disengage were dispatched by aircraft and carried by the chief of staff of the tank army, Maj.-Gen. D.D. Vakhmet’ev. The essence of the orders to Rybalko was that he should leave only a light force to cover Lvov, bringing his main body in an outflanking movement to the north-west and into the area of Yavorov, thus cutting the German escape route to the west and leaving a force from 3rd Guards free to co-operate with 60th and 38th Armies in the actual reduction of the city.

Marshal Koniev did not wish to see his most powerful forces tied down in front of Lvov while the Germans organized a defence line on the river San and the Vistula. The right-flank armies of the Front, 1st Guards Tank Army and 13th Army, were already racing for the San, coming down from the north-east, and on the evening of 23 July, Katukov’s tanks reached the San near the town of Yaroslav. Twenty-four hours earlier Rybalko detached two tank brigades and two battalions of motorized infantry to hold the line near Lvov, setting his main body on the move to the area around Yavorov. By the evening of 24 July, 3rd Guards was deployed in the triangle Yavorov–Mostiska–Sudovaya Vyshnaya, from which it launched attacks from the east against Peremysl and from the west against Lvov. Lelyushenko’s tank army, or at least one corps (10th), was already in Lvov; Lelyushenko’s orders specified an attack on Sambor to the south-west of Lvov to cut another German escape route, but Lelyushenko decided to take Lvov ‘on the way there’—

po puti

. The bulk of 4th Tank Army closed on Lvov by the evening of 22 July, while 10th Tank Corps was actually inside the city, though cut off from its fellows.

So the concentric attack on Lvov took shape and opened with all forces on 24 July: Kurochkin’s 60th Army from the east and north-east, 10th Tank Corps in the southern suburbs, Rybalko’s 6th Guards Tank Corps from the west, leaving only one escape route for the German troops, the south-westerly Lvov–Sambor road. It took three days and nights of heavy fighting to clear the ancient Ukrainian city. Kurochkin’s riflemen fought their way in street by street, Poluboyarov’s 4th Guards Tank Corps from the east linked up with 10th Tank Corps in the south, but to the west Rybalko’s corps was held in check. On the evening of 26 July the Soviet commanders saw signs of a German withdrawal to the south-west and at dawn the next day Soviet armies attacked from all directions—from the west (3rd Guards Tank), from the north, east and south-east (60th Army) and from within the city itself (4th Guards Tank and 10th Tank Corps). Almost simultaneously 3rd Guards Tank Army, supported by units from 1st Guards Tank Army, stormed Peremysl during the night.

Smashing German resistance at Lvov, together with the capture of Rava Russkaya, Peremysl, and Vladimir–Volynskii, broke Army Group North Ukraine

in two; Fourth

Panzer

, fighting off the Russians all the way, fell back on the Vistula, while First

Panzer

(with the 1st Hungarian Army) drew back to the south-west and down to the Carpathians. Rybalko’s 3rd Guards Army now received orders to advance to the Vistula, to force a crossing on the night of 29 July, seize a bridgehead on the western bank and capture the town of Sandomierz. Katukov’s tank army was directed to the Vistula just south of Sandomierz at Baranow, Sokolov’s cavalry-mechanized group was to force the river to the north, at Annopol, and Pukhov’s 13th Army was directed to the Vistula along ‘the Sandomierz axis’. Zhadov’s 5th Guards Army (Front reserve) was also moved to the Vistula, where Koniev’s main strength was gathering—two infantry armies (5th Guards and 13th), two tank armies (1st Guards and 3rd Guards) and a ‘cavalry-mechanized group’.

Koniev’s armies took the Vistula at a rush. By the evening of 30 July Rybalko’s tank crews, accompanied by Sokolov’s cavalry, had crossed the river and taken three smallish bridgeheads north and south of Annopol, but these hastily improvised crossings failed to provide the requisite strength and impetus to enlarge the bridgeheads. Pukhov’s 13th Army and the lead units of Katukov’s 1st Guards Tank Army were more successful in the Baranow area; Pukhov got two divisions over, the boats and rafts carrying Soviet soldiers often racing side by side with the makeshift ferries laden with retreating German soldiers. By the evening, 305th Rifle Division (13th Army) had carved out a bridgehead five miles deep and with a frontage of some eight miles. Behind the infantry and the armour came the bridging units, the 20th Bridging Battalion and the 6th Bridging Brigade, which by 1 August put down, under persistent German air attack, heavy bridging equipment and pontoons capable of carrying loads up to fifty–sixty tons and sixteen tons respectively: these carried the men and equipment for two corps plus 182 tanks, 11 armoured carriers, 55 guns and 94 lorries across the Vistula into the ‘Sandomierz’ bridgehead.

On the left flank Koniev ordered Lelyushenko to swing 4th Tank Army to the south-west on to Sambor (where he should have been in the first place), to take Drohobych and Borislav off the march by the evening of 28 July, and in co-operation with the right-flank formations of Grechko’s 1st Guards Army to seal off the German route to the San to the north-west. The German rearguards, fighting with great skill and very stubbornly, did not let Lelyushenko pass so easily and held 4th Tank Army at Drohobych. The infantry armies of the left flank, 1st Guards and 18th Army, did nevertheless enjoy some successes of their own; Grechko’s 1st Guards took the regional centre of Stanislav on 26 July and by the end of the month 18th Army captured the rail junction of Dolina and cut the motor road leading through the Carpathians into the Hungarian plain. Though the main task of 1st Ukrainian Front lay now in a north-westerly direction towards the Vistula, Koniev ordered the two left-flank armies to seize the passes over the Carpathians leading to Hummene, Uzhorod and Mukachevo. If Army Group North Ukraine had been split down the middle, 1st Ukrainian Front was

now operating on two diverging axes, the ‘Sandomierz axis’ and the ‘Carpathian axis’, thereby complicating the problem of controlling the separate armies; and with a massive battle building up for the Sandomierz bridgehead, Koniev at the end of July consulted the

Stavka

, suggesting that the armies on the Carpathian axis should come under independent command. He was informed that there was one unassigned Front administration, that of Col.-Gen. I.E. Petrov (lately in the Crimea), and within a few days Petrov’s new command—4th Ukrainian Front—was officially activated to take control of operations in the foothills of the Carpathians.

Meanwhile Rokossovskii’s left-flank armies—8th Guards, 69th Army, 1st Polish Army and 2nd Tank Army—raced on to the Vistula and up to Warsaw. Behind them lay the ghastly discovery of the ‘death-factory’ of Maidanek, lying just to the west of Lublin, where more than a million people died and many thousands more suffered the sub-human existence reserved for the inmates of the camps. Maidanek was only the first of such horrors upon which the advancing Red Army stumbled—Treblinka, Sobibor, Auschwitz–Birkenau, Belzec and Stutthof, all extermination camps with their mountains of dead. Maidanek was but a grisly foretaste. Chuikov’s and Kolpakchi’s mobile columns were advancing north-west but Chuikov was baffled by the apparently contradictory orders he received—‘halt the advance’, ‘consolidate positions’, ‘resume the advance’: the tempo of the Soviet advance as a whole was beginning to flag as the armies moved further and further from their bases, and now the confusion of instructions tended to slow 8th Guards and 2nd Tank Army in their sweep to the Vistula. Further to the east, on the outer edge of these left-flank armies, General Kryukov’s ‘cavalry-mechanized group’ drove on towards Siedlce, which the Front command hoped to seize off the march towards the evening of 24 July. Siedlce, sixty miles west of Brest-Litovsk, was an important road and rail junction, one that played a significant part in supplying Brest-Litovsk itself—and, equally, could serve as an escape hatch for German units trapped at Brest; but before 11th Tank Corps could rush Siedlce, German armoured and infantry reinforcements moved in. With Soviet tanks in the suburbs at dawn on 25 July, German units swept in from the north and north-east, displaying every intention of holding the town. German bombers attacked the Soviet tank units and armoured counter-attacks forced 11th Corps to take up defensive positions; heavy fighting surged through the southern outskirts of Siedlce, while Kryukov detached 65th Tank Brigade to deal with a German armoured column moving down from the north-west. Though sections of the town were in Soviet hands by 26 July, the group commander decided to launch a concentric attack the next day, surround Siedlce completely and then storm it, a task assigned to 11th Corps and 2nd Guards Cavalry Corps. Though this cleared most of the town, it proved impossible to dislodge the

SS

troops and elements of three German infantry divisions holding the northern part of Siedlce. Only on 31 July, after a powerful barrage and the use of a regiment of bombers, could 11th Corps, cavalry units and riflemen from

47th Army clear the Siedlce area, giving Soviet troops undisputed possession of two major communication centres—Siedlce and Minsk–Masowiecki—on the approaches to Warsaw.

On the morning of 27 July the first echelon of 2nd Tank Army—3rd and 8th Guards Tank Corps—moved off in the general direction of Warsaw–Praga from the Deblin area. Chuikov’s 8th Guards still received contradictory orders: on 26 July, Chuikov was ordered to reach the Vistula on the Garwolin–Deblin sector, keeping his army in ‘compact order’ and ‘in full readiness for a major engagement’, with forward detachments sent ahead to a considerable distance—only to be told a few hours later that ‘8th Guards Army will not become dispersed … the Army will have its main grouping on the right flank, bearing in mind that the activization of enemy operations is most likely in the direction of Siedlce–Lukow’. Col.-Gen. Chuikov nevertheless realized that sooner or later his formations must force the Vistula, even though they were coasting alongside it at the moment; Chuikov himself set out to choose a particular sector, and a little to the north-west of Magnuszew, in the village of Wilga, the Army commander conducted his own reconnaissance, driving into the middle of a Polish crowd in holiday mood, taking the air on the Vistula bank and enjoying the music of accordions. From observation of the western bank, it was clear that the Germans did not expect an attack here and Chuikov plumped for the Magnuszew sector to make his crossing of the Vistula. Returning to his own

HQ

, Chuikov reported to Rokossovskii about his decision, which the Front commander noted and promised to reply the next day. At noon on 30 July Rokossovskii came on the line and authorized Chuikov to prepare plans for forcing the Vistula on the Maciejowice–Stezyce sector (south of the sector Chuikov had himself chosen), giving him three days’ notice; not unnaturally, Chuikov asked for ‘the Wilga sector’, the one he had already chosen, and pointed out that he could begin operations ‘early tomorrow morning, not in three days’ time, since all preparatory work has been done here’. He submitted at once plans specifying 1 August as the operational date, and this was approved. On the morning of 1 August Chuikov’s men launched their boats into the darkness; the scouts reached the western bank and had cleared the first line of German trenches before the artillery opened fire, as the rifle battalions began their crossing.