The Road to Berlin (8 page)

Read The Road to Berlin Online

Authors: John Erickson

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Former Soviet Republics, #Military, #World War II

Voronov, Rokossovskii and Malinin were unanimous in their opinion that the Don Front should carry the main attack. Voronov himself was all for the Soviet forces on the perimeter being unified into one force under Don Front command and he was aware that the

Stavka

would not object overmuch to this. At the same time, the stipulated ‘five-six days’ in which to wipe out Sixth Army now appeared wholly unreasonable, after an inspection of the defensive positions (built earlier for the Red Army and now manned by German infantry) and an examination of the strengths of Soviet divisions. Plan

Koltso

, which was ready by 27 December, proposed one main attack from west to east designed to split the pocket in two: 65th, 21st and 24th Armies of the Don Front would attack along an axis running through Baburkin to the workers’ settlement at Krasnyi Oktyabr–Gumrak–Alekseyevka. With Soviet divisions down to less than half-strength, Voronov planned to make massive use of artillery to blast passages for the infantry. Once drafted, Plan

Koltso

was put on an aircraft for Moscow on 27 December. As Voronov sat back to wait, the chance of serious revision of the plan seemed to him remote since the General Staff had generally confirmed the ideas in a series of exchanges over the telephone.

However, Voronov’s plan came in for some rough handling by the

Stavka

, which the signal of 28 December made plain:

Comrade Voronov:

The main shortcoming of the plan you presented for

Koltso

lies in the fact that the main and the supporting attacks diverge from each other and doubtful outcomes which might prejudice success are nowhere eliminated.

In the

Stavka’s

view, your main task in the first stage of the operation must be the splitting up and annihilation of the western grouping of encircled enemy troops in the Kravtsov–Baburkin–Marinovka–Karpovka area in order to turn the main attack by our troops south from the Dmitrovka–Baburkin area into the Karpovka railway station district, and to direct a supporting attack by 57th Army from the Kravtsov–Sklyarov area into linking up with the main attack, so that both join at Karpovsk railway station.

In line with this should be organized an attack by 66th Army through Orlovka towards

Krasnyi-Oktyabr

and to meet this—an attack mounted by 62nd Army so that both attacks would link up and thus cut off the factory district from the main enemy forces.

The

Stavka

instructs you to revise your plan on the basis of these foregoing suggestions. The

Stavka

confirms the date for opening operations [6 January 1943] as presented by you in your first plan. The first phase of the operation will terminate 5–6 days after its commencement. The plan for the second stage of operations will be presented through the General Staff on January 9, utilizing the first results of the first stage.

[VIZ

, 1962 (5), note to p. 77.]

Nevertheless, Voronov gained something: the

Stavka

agreed to a unified command, decided on reinforcing the artillery needed for the operation and despatched 20,000 men as an infantry component. On 1 January 1943, 62nd, 64th and 57th Armies were subordinated to the Don Front, giving Voronov and Rokossovskii a force of thirty-nine rifle divisions, ten rifle brigades, thirty-eight High Command Artillery Reserve regiments, ten Guards Mortar (Katyusha) regiments, five tank brigades, thirteen tank regiments, three armoured trains, seventeen

AA

regiments, six ‘fortified garrisons’ and fourteen flame-thrower companies. The entire force on the inner encirclement comprised forty-seven divisions (218,000 men), 5,610 guns and mortars, 169 tanks and 300 planes. It was little wonder that Stalin wanted this force freed for other operations as speedily as possible.

On the morning of 3 January, Voronov, Rokossovskii and Malinin met to review the state of the preparations for the attack in three days’ time. There was little to encourage optimism. The reinforcements and supplies lagged behind on the railways, although Voronov had pressed Khrulev to speed things up. To attack on time was a risk; to ask for a postponement meant running foul of Stalin. There was nothing for it, however, in view of the delays with men and ammunitions, but to seek four more days, reasons for which Voronov set out in his letter to the

Stavka:

To proceed with the execution of

Koltso

at the time authorized by you does not seem possible owing to the 4–5 day delay in the arrival of reinforcement units, trains with reinforcement drafts and ammunition trains.

To speed up their movement we agreed to unloading many trains and transport columns at a considerable distance from the points agreed in the plans for detraining and unloading. That measure involved the loss of a great deal of time in then shifting units, reinforcements and ammunition up to the front.

Our correctly proportioned plan was then thrown out of gear by the unscheduled movement of trains and transports to comrade Vatutin’s left wing. Comrade Rokossovskii requests that the opening of operations be changed to plus four. I have personally checked all calculations.

All this impels a request for you to authorize commencement of

Koltso

at plus four.

[VIZ

, 1962 (5), p. 81.]

Stalin telephoned at once to find out what Voronov meant by ‘plus four’. The rebuke was stinging when it came:

You’ll sit it out so long down there that the Germans will take you [Voronov] and Rokossovskii prisoner. You don’t think about what can be done, only about what can’t be done. We need to be finished as quickly as possible there and you deliberately hold things up. [

Ibid.]

Grudgingly Stalin gave Voronov ‘plus four’.

Koltso

was now to open on 10 January.

Faced with the problem of relating requisite strength to maximum speed, there was some justification for Stalin’s fierce impatience with Voronov. During the last ten days of December 1942 the

Stavka

had worked feverishly to finish the planning for the massive counter-offensive designed to roll over the German southern wing to engulf Army Groups A, Don and B. At the northern end of the Soviet–German front, the Leningrad and Volkhov Front command received confirmation of orders despatched on 8 December to proceed with the de-blockading of Leningrad. The freeing of Leningrad, the destruction of Sixth Army at Stalingrad, a Soviet offensive into the eastern Donbas, an attack in the direction of Kursk and Kharkov, and the trapping of Army Group A in the Caucasus would signal the general expulsion of German forces from Soviet territory, and the destruction of the entire southern wing of the German army would offer a decisive strategic success. At the end of 1942 the Soviet command reckoned that twenty-five per cent of German strength on the southern wing had been eliminated: Sixth Army, one of the most powerful in the

Wehrmacht

, was encircled and the force sent out to its relief defeated; Fourth

Panzer

had been severely mauled; 3rd and 4th Rumanian Armies had been battered to pieces; and 8th Italian Army for all practical purposes shattered. With the distance between inner and outer encirclement now some sixty-five miles, Paulus and his men were doomed. The Soviet outer encirclement ran from Novaya Kalitva in the north (Voronezh Front) through Millerovo, west of Tormosin and east of Zimovniki. The time had come for a concerted attack on the three German army groups in the south.

In the early hours of 22 December, Golikov, commander of the Voronezh Front, attended a

Stavka

session which discussed the operational plans for a second strike on the middle reaches of the Don, aimed this time at the 2nd Hungarian Army and the remnants of 8th Italian Army. This attack would clear enemy forces from the Ostrogorzhsk–Kamenka–Rossosh area (between Kantemirovka and Voronezh), an indispensable prelude to developing a Soviet offensive in the direction of Kursk and Kharkov. The South-Western Front would at the same time attack in the direction of Voroshilovgrad. Golikov’s new offensive would bring his forces into the south-western sector of the Voronezh

oblast

between the Don and the Oskol, the shortest route to Kursk and Kharkov, and a key railway network. In Stalin’s plans to liberate the Kharkov industrial region, the Donbas and the northern Caucasus, the rail links had a key role to play; both the Voronezh and South-Western Fronts were severely restricted by lack of rail facilities. (The storming of Stalingrad would also reopen direct rail links with the north Caucasus.) Golikov’s orders were precise enough: to attack on his centre and on his left, to eliminate enemy forces between Voronezh and Kantemirovka, and to seize the Liskaya–Kantemirovka rail link (upon which both the Voronezh and South-Western Fronts could then be based for future offensive operations aimed at Kharkov and the Donbas). To secure Voronezh Front operations from the south, Vatutin was to use his 6th Army in an attack ‘in the general direction of Pokrovskoe’. General Zhukov and Col.-Gen. Vasilevskii would ‘co-ordinate’ the offensive, which was timed for mid-January.

On the Trans-Caucasus Front, Tyulenev had submitted his own plan for an offensive designed to liberate Maikop: his front consisted of two elements, the right wing holding the Kayasula–Mozdok–Bakhan line and the left running along the coast, the ‘Black Sea Group’ under Petrov. The left wing held First

Panzer

Army; the right, 17th Army. In November Tyulenev had been ordered to strengthen Petrov’s group with troops and artillery, movement which involved the Front command in vast construction work to build roads and erect bridges. At the same time, Tyulenev held back a considerable body of troops—10th Guards Rifle Corps, 3rd Rifle Corps and two rifle divisions—on his right wing, the ‘Northern Group’, in spite of the

Stavka

’s insistence that they should go to Petrov.

On 29 December Tyulenev was told to scrap his plans for an attack on Maikop and to prepare an entirely new operation. The encirclement of Army Group A was to be accomplished now by two Soviet drives, one by the ‘Black Sea Group’ (Trans-Caucasus Front) attacking towards Krasnodar-Tikhoretsk and a second by the Southern Front (the new designation of the Stalingrad Front from 1 January 1943), using 51st and 28th Armies to advance on Salsk-Tikhoretsk, followed by a joint advance on Rostov. In addition, the Black Sea Group would attack right-flank units of Seventeenth Army in the Novorossiisk area and seize the Taman peninsula, the German escape route to the Crimea. Neither Petrov nor Tyulenev were exactly enamoured of the

Stavka

plan for the Trans-Caucasus Front. Moving troops through mountains during the worst period of the winter weather, or shifting them from Vladikavkaz to Poti by rail and thence by sea to the northerly sections of Petrov’s coastal forces, were equally difficult prospects. After debating the problem with Petrov, Tyulenev telephoned Stalin in an effort to have the ‘Maikop operation’ restored. Stalin refused: Tyulenev would attack from the Black Sea Group, the ‘Krasnodar variant’ stood, and to cut off Army Group A the Trans-Caucasus Front would go for Bataisk and Tikhoretsk to cut escape routes at Rostov and Eisk. Petrov, who had defended Sevastopol, wryly admitted to Tyulenev that this one was a ‘tough nut’.

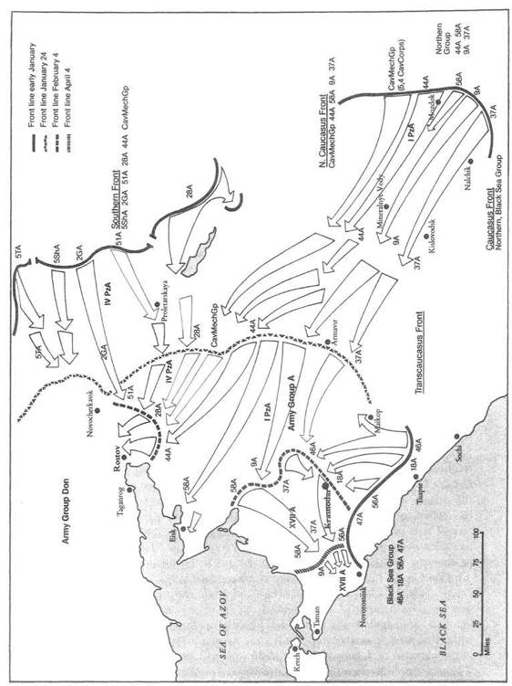

Map 1

Operations in the North Caucasus, January–April 1943

To crack ‘the nut’, Tyulenev and Petrov proposed two operations, Operation

Gory

(‘Heights’) to break Seventeenth Army defences at Goryschii Kluch and then a drive to the river Kuban and Krasnograd; Operation

More

(‘Sea’) would use the left flank of 47th Army and a seaborne landing at Yuzhnaya Ozereika to clear German forces from Novorossiisk. This met with Stalin’s approval, but he emphasized to Tyulenev that First

Panzer

was beginning to pull out of the northern Caucasus—shipping back all unnecessary equipment, demolishing dumps and blowing up roads. Petrov must get to the Tikhoretsk area and stop enemy material being moved westwards. The main assignment was formalized in the

Stavka

directive of 4 January, which prescribed forming a powerful column from the ‘Black Sea Group’ to strike towards Bataisk–Azov, ‘slip into’ Rostov from the east and cut off Army Group A. Stalin himself gave Tyulenev his orders:

Tell Petrov to start his movement on time, without holding back for anything even for an hour and without waiting for reserves to move up. [Tyulenev,

Cherez tri voiny

, p. 250.]

When Tyulenev pointed out that Petrov had no experience in breakthrough operations, Stalin told Tyulenev to go to the Black Sea Group himself and see that these orders were carried out. Meanwhile First

Panzer

had begun to fall back towards the Kuma, a situation which Maslennikov in command of the ‘Northern Group’ (44th, 58th, 9th, 37th Armies, 4th Kuban and 5th Don Cavalry Corps) failed dismally to exploit, much as in October he had bungled the defence. Still in fear of a German attack on Groznyi and Dzaudzhikai, he had closed up on his left and centre, thus depriving the right flank of badly needed strength. With signals completely disorganized he lost touch with the formation trying to attack First

Panzer

Army. Vasilevskii on 7 January was obliged to intervene in the interests of speeding the attack; on his orders, 4th Kuban, 5th Don Cavalry Corps and tank units were assembled into a ‘cavalry-mechanized group’ under Lt.-Gen. N.Ya. Kirichenko and given instructions to strike north-westwards for Armavir or Nevinnomysska in an effort to trap German forces on that axis. Maslennikov was told to leave only a minimum of forces on his left; while Kirichenko’s mobile force moved on Armavir, 44th Army would attack in the direction of Stavropol. Petrov meanwhile had to report to the

Stavka

on 7 January that ‘full concentration of forces assigned primarily [to me] is impossible’.

The winter gales seriously interfered with supply by sea and since 5 January rainstorms had washed away roads and brought floods which swept down bridges; heavy artillery was stuck in the mountain passes. Petrov’s operation was postponed for four days, until 16 January.