The Road to Berlin (88 page)

Read The Road to Berlin Online

Authors: John Erickson

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Former Soviet Republics, #Military, #World War II

Towards the end of August the Soviet fronts in the north—1st, 2nd and 3rd Baltic, together with Govorov’s Leningrad Front—ground their way slowly through Estonia and Latvia, fighting off heavy German counter-attacks mounted with great skill amidst the rivers, marshes and thick forests of this northern theatre. The veterans of Army Group North provided some of the toughest and most experienced German battle groups on the Eastern Front. With Finland out of the war, both the Germans and Russians could devote their full attention and greater resources to this southerly basin of the northern theatre, a change that affected Estonia almost at once, for more men were available to Govorov on the Leningrad Front (thus diminishing his dependence on Maslennikov’s 3rd Baltic Front) and Schörner could contemplate evacuating Estonia now that the need to prop up Finland had gone: additional troops were freed to fight off the main Russian threat to the Baltic bastions the German command intended to hold. The

Stavka

meanwhile concluded that the time had come to deliver the

coup de grace

to Army Group North: between 26 August and 2 September fresh directives descended on the Soviet Front commanders, instructing them to prepare a major offensive designed to clear the Baltic states and, above all, to take Riga.

Under these revised schedules and assignments, Govorov took over the Tartu sector from 3rd Baltic Front, the prelude to an attack aimed in the direction of Rakevere–Taps, breaking into the German rear and driving on Tallinn. The three remaining Baltic fronts were committed to a series of concentric attacks aimed at Riga: Maslennikov’s 3rd Baltic would attack on both flanks, co-operating with the 10th Guards Army of 2nd Baltic Front to destroy German forces east of Smiltene (with the

Stavka

supplying an additional army, the 61st, plus one rifle

corps from Govorov’s front); Yeremenko’s 2nd Baltic Front was aimed at Riga itself, an offensive to be carried through in co-operation with Maslennikov and Bagramyan whose task it was with 1st Baltic Front to wear down German forces east of Dobele, to block any breakthrough in the direction of Jelgava and Shaulyai—the axis of the fierce fighting in the past month—while attacking on the left flank with the object of reaching Vetsmuzhei and the mouth of the western Dvina. This would push Soviet armies on to the shore of the gulf of Riga in the general area of Riga itself and thus isolate Army Group North from East Prussia. The

Stavka

orders prescribed that the three Baltic Fronts were to go over to the offensive on 14 September, followed three days later by the Leningrad Front, where regrouping needed more time.

The size of this offensive indicated that the

Stavka

intended to go for the kill. The concentric attacks were designed to encircle the bulk of the German divisions in the Baltic states, with Bagramyan’s thrust severing Army Group North from the rest of the German forces and driving the Germans to the sea, where a sea-borne blockade would keep them sealed off while deep frontal attacks destroyed the entire Army Group. Along the 500-kilometre front, the

Stavka

proposed to deploy 125 rifle divisions and seven tank corps—900,000 men, 17,483 guns and mortars, 3,081 tanks and 2,643 aircraft (supplemented by the naval aircraft of the Baltic Fleet). On the first days of the Soviet offensive the

Stavka

plan called for the commitment of ten ‘all-arms’ armies and three armoured corps, the equivalent of 95 rifle divisions of which 74 were to be employed on the ‘breakthrough sectors’ (with a total frontage of 76 kilometres), which meant committing more than three-quarters of the available Soviet strength to the breakthrough, leaving the secondary sectors under relatively light attack—a blunder which cost the Soviet command dear almost from the outset, since it left the Germans free to transfer units in strength to threatened lines and positions.

For the forthcoming offensive, Soviet armoured strength almost doubled, with Bagramyan disposing of 1,328 tanks and

SP

guns. Ths

Stavka

directive stipulated that Bagramyan’s armour must be used to ‘develop gains along the Riga axis’, to which Bagramyan responded by deploying 5th Guards Tank Army and two tank corps (1st and 19th) on his left and at the centre. Yeremenko disposed of 287 tanks, more than half of which were assembled into ‘mobile groups’, 133 being assigned to the infantry-support role: Maslennikov used most of his 290 tanks and

SP

guns in an infantry-support role, leaving only 53 in reserve or for use with ‘mobile groups’. Splitting up the armour in this fashion proved to be a very unsatisfactory solution, largely because it left insufficient tanks for use in infantry-support roles. This weakened the infantry, many of whose units and formations consisted of newly conscripted men taken into the army on the line of march through Belorussia and the Baltic states, raw recruits without any previous military training who were about to be committed to the most searing and intensive infantry fighting in any theatre. Many of the German defensive positions were protected by rivers, which meant assault crossings. Across the length

of the front the terrain also assisted the tenacious German defence, which relied on preserving men and equipment by ‘emptying’ the forward positions during the preliminary Soviet bombardment, and holding units in reserve to put in counter-attacks which blunted or deflected the Soviet infantry attacks in the wake of the barrage. Bagramyan’s unit and formation commanders seemed to have a good idea of what faced them on the German side, but Maslennikov and Yeremenko failed to register the German defences properly: reconnaissance on the 2nd Baltic Front began only a few hours before the main attack was due, and on the 3rd Baltic Front (in the area of 67th Army) it was thought that the German defences consisted of only a couple of lines of trenches, ignoring completely the defensive positions on the heights and the heavily fortified villages.

Preceded by an hour’s artillery bombardment (extended to two on some sectors), the three Baltic fronts renewed the Soviet offensive on 14 September. Bagramyan’s attack, preparations for which had been carefully camouflaged, came as an unpleasant surprise for units of the German Sixteenth Army transferred to the southern side of the Dvina. Striking out along a seven-mile sector, the assault groups penetrated several miles on the first day, with Beloborodov’s 43rd Army fighting north of Bausk making the greatest progress and breaking into the second zone of the German defences, bringing 3rd Guards Mechanized Corps into the action. Fighting off a score of German counter-attacks, the Soviet assault divisions pushed forward to the ‘eastern Jelgava defence line’, capturing Bausk, Jelgava on the Dvina and Eckau; by the evening of 16 September advanced units of the mobile formations were drawing up to Baldon and reaching for the western Dvina, bringing Soviet units closer to the’ southern suburbs of Riga.

Attacking on the northern bank of the Dvina, Maslennikov and Yeremenko ran into stiff German opposition which slowed the Soviet advance very considerably. On 15 September Maslennikov’s Front, aimed from the north-east in the general direction of Riga, began a converging attack on Valk, the fortified communications centre given additional protection by the marshes and thick forest surrounding it. Possession of Valk and the ‘Valk line’ secured the communications of the German force in Estonia (Operational Group ‘Narva’), which meant that the German defenders would not lightly give it up. After four days of bitter fighting between units of the German Eighteenth Army and Maslennikov’s units, Valk fell to the Russians. Yeremenko’s 2nd Baltic Front armies were meanwhile attacking to the north-west of Madona and in the area of Plavinas on the Dvina, another German bastion which had to be toppled. The new offensive got off to a bad start, much as Yeremenko feared; the initial artillery bombardment was mounted in insufficient depth, the German positions were not destroyed in any depth and the Soviet attack came as no surprise to the German command. German units retired methodically from one system of defences to another, forcing Soviet troops to reorganize for each new step in this ‘offensive’ when as little as 2–3 miles separated the defensive lines. Three times Yeremenko introduced 5th Tank Corps to finish off the ‘breakthrough’, only to have it effectively beaten

back. The broken terrain, small rivers, innumerable lakes and dense clumps of forest all gave the German commanders ample cover for ambushes and for camouflaging their defences. Col.-Gen. Sandalov, Yeremenko’s chief of staff, also deplored the tactics of making single attacks where the Germans were ready and waiting, but such was the nature of

Stavka

directives (and Stalin’s own refusal to countenance even tactical modifications) that outflanking could not be practised on any scale. Soviet units could only try to batter their way through the deeply echeloned German defences, admirably fitted out with weapon-pits, machine-gun positions, artillery and mortar firing points; command and observation posts, many of them substantial stone structures, were liberally distributed throughout the whole area and served as additional fortification when necessary. Minefields created an extra hazard, laid not in large fields but in clumps both at the forward edge of the German defences and throughout the depth of the positions.

With only forty miles separating Yeremenko from Riga, the German command lost no time in organizing a series of powerful counter-attacks to block the Soviet thrusts. With progress measured only in a few thousand yards, Soviet infantrymen faced the attacks of five German divisions supported by well over a hundred tanks, stabbing at every Soviet move. During 15–16 September the 3rd Shock Army and 22nd Army beat off one attack after another finally pushing the Germans back to the western bank of the Oger but making only a few thousand yards of ground. In the area of Ergli a powerful German armoured force drawn from 14th

Panzer

Division launched a series of attacks on 15 September, committing up to 200 tanks. But as Schörner fought off Yeremenko and threw in more armour against Bagramyan to the west of Jelgava and in the area of Baldon, Govorov’s delayed offensive with the Leningrad Front finally opened on 17 September and resulted in very rapid gains, putting Group ‘Narva’ at risk and speeding up the decision to pull back the whole Army Group along a line running from the gulf of Finland to the western Dvina.

Govorov’s front attacked from the Tartu sector, aiming to break through the German defences by means of concentric attacks: Fedyuninskii’s 2nd Shock Army was already in its new position by 12 September, having moved southwards through Gdov and across the neck of land between the Peipus and Pskov lakes to take the place of 8th Army south of Tartu, deploying five rifle corps (including the 8th Estonian Corps) and one ‘fortified district’ unit, the 14th, a new unit for 2nd Shock and one whose commander scarcely impressed Fedyuninskii. The Front plan called for Fedyuninskii to strike north and north-west, destroying German units in the Tartu area, followed by the destruction of the whole ‘Narva’ Group as the 8th Army struck from the line of the Narva and advanced on Rakevere. Ahead of Fedyuninskii lay some five German divisions, their fortified lines by no means complete but the defence again facilitated by marsh and forest. On 17 September Fedyuninskii attacked with two corps in the lead—Simonyak’s 30th Guards and Pern’s 8th Estonian: by the end of the day, Soviet troops were ten miles deep into the German defences along a fifteen-mile front. To exploit this success Fedyuninskii committed Colonel Kovalevskii’s ‘mobile group’ made up of tank brigades and tank regiments, followed by another group under Colonel Protsenko on 19 September. The German command was already pulling its

SS

units back from the Narva sector on the evening of 18 September, as the threat to their rear from Fedyuninskii grew by the hour. The German withdrawal at once brought 8th Army into action and during the night of 19 September units of the 8th attacked, driving westwards for Rakevere. Within twenty-four hours Soviet mobile units took Rakevere and linked up on the left flank with the 2nd Shock Army at Lokusu on the western side of lake Peipus. Fedyuninskii’s army now received orders to swing south in order to clear the shore of the gulf of Riga and to capture Parnue not later than 25 September, but while the main body swung south and south-west Pern’s Estonian corps continued in a north-westerly direction, towards Tallinn, the Estonian capital. Lt.-Gen. Pern formed his own ‘mobile group’ and pushed on with all speed to the capital. On 22 September the city was cleared of German troops and two days later Fedyuninskii—forty-eight hours ahead of schedule—reached Parnu, pushing on still further to cross the frontier into Latvia. Then, to Fedyuninskii’s utter astonishment, orders from the Front command brought his pursuit to a halt, even as his lead infantry formations seemed to be within striking distance of Riga.

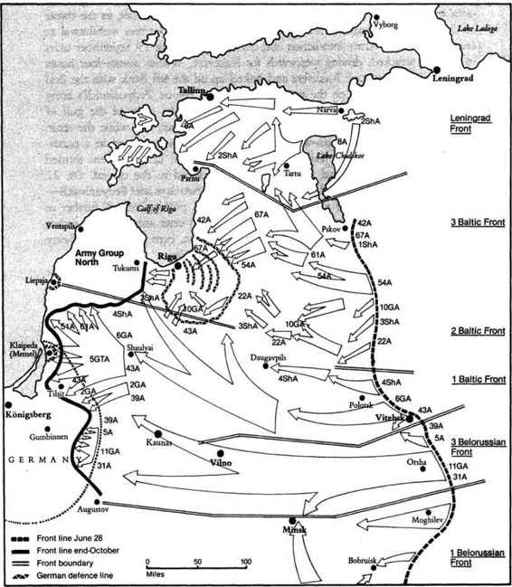

Map 11

The Soviet drive into the Baltic states, July–November 1944

Even before Fedyuninskii was halted in his tracks, it was plain that the attempt to take Riga by direct assault could not succeed. Maslennikov and Yeremenko were pinned down by heavy German attacks, their progress drastically reduced. Though Bagramyan had fought his way to the southern outskirts of Riga (Soviet units were only about fifteen miles from the city), to assault the city while the Germans held the right bank of the Dvina and the coast covered from the east by the lower reaches of the river Aa presented formidable problems. Schörner, while pulling his Army Group back to the final defence lines, smashed into the Soviet positions with two major counter-blows from the region of Baldon itself and once again in the area to the south-west of Dobele. On Bagramyan’s left flank, in the Dobele area, the newly constituted Third

Panzer

Army (moved from Army Group Centre) hurled a dozen motorized battalions and almost 400 tanks into fierce attacks which lasted for a full five days, hammering at Bagramyan’s flank armies (51st Guards and 5th Tank Army). From 16–22 September German tank units fought furiously to stave in the Soviet defences but only managed to dent the lines held by 6th Guards Army south of Dobele, all at the cost of 131 tanks and 14 assault guns. The German attacks did nevertheless prevent Bagramyan loosing his second assault group in a northerly attack from Jelgava towards Kemeri (to the west of Riga) and the Gulf of Riga.