The Road to Berlin (92 page)

Read The Road to Berlin Online

Authors: John Erickson

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Former Soviet Republics, #Military, #World War II

On Christmas Day, when lead German armour was only three miles from the Meuse at Celle but already bumping into the American 2nd Armoured Division, a despondent Col.-Gen. Guderian drove from his headquarters in Zossen to the ‘Adlerhorst’ redoubt near Giessen for a conference with Hitler and his other military advisers. Convinced by now of the futility of pressing the attack in the west which could not lead to a decisive German success, Guderian intended to ask the

Führer

to break off the Ardennes offensive and move all available forces to the eastern front, where the warning lights were already flashing. Though Chernyakhovskii’s hammering at the doors of East Prussia had ceased for the moment and a relative calm had settled on the Narew and Vistula lines, the battle in Hungary had intensified when Tolbukhin’s 3rd Ukrainian Front joined Malinovskii’s 2nd, and fierce fighting was now raging for Budapest, as the two Soviet fronts battled under hard winter conditions to close the ring on the German defenders. The trap was all but closed.

Guderian went well armed for this confrontation with the

Führer

. Gehlen, head of

Fremde Heere Ost

, prepared a formidable brief indicating that a huge wave of Soviet armies must shortly break over the

Reich

from the east. The Soviet and German armies presently faced each other across a drastically shortened front, cut from 4,400 kilometres to little more than 2,000; the line ran from Memel on the Baltic, along the border of East Prussia to the line of the Vistula east of Warsaw, thence across Poland and eastern Czechoslovakia to the river Danube north of Budapest, lake Balaton and the river Drava, at which junction the Red Army gave way to Marshal Tito’s Yugoslav ‘National-Liberation Army’ holding its own line running east of Sarajevo and on to the shore of the Adriatic at Zadar. Only the German divisions bottled up in Courland remained on Soviet territory, a useful reserve but one imprisoned by Soviet troops. Massed along the eastern borders of Germany was a gigantic Soviet force made up of almost six million men, deployed on nine fronts each of which was preparing its own operations for the final campaign. Gehlen’s report, based on interrogation of prisoners and an assessment of Soviet operational intentions (dated 5 and 22 December respectively), made grim reading. It announced a major Soviet attack ‘towards the middle of January’ at the latest; and the tabulation of Soviet Front strength left no doubt what was in store for the

Ostheer

, destined for destruction by the Red Army. The essence of the Soviet plan consisted of drawing German reserves away from Army Group A and from the centre by heavy attacks in Hungary, after which the Soviet command would be free to develop its main assault on Germany’s vitals.

Though the front had shortened, it was still too long for Guderian’s peace of mind. The divisions in Courland had remained on Hitler’s express insistence; he ruled out ‘timely evacuation’ of the Balkans and of Norway, and he overruled the proposal that the

Hauptkampflinie (HKL)

should be separated by several miles from the

Grosskampflinie

(the ‘main battle line’), thus forcing the Russians to waste men and munitions on assaulting the first line—the

HKL

—only to crash into the real German strength at the second. The result of ignoring this advice was simply an invitation to disaster: major defensive positions and the few available reserves were bunched up to present one prime target, all under the barrels of the Russian guns. Not content with throwing out Guderian’s arguments on tactical methods, Hitler also debunked the talk of a forthcoming Soviet attack as so much rubbish, dismissing Gehlen’s reports out of hand and ridiculing the idea of a mass of Soviet armies about to fall on the

Reich

. In the

Führer’s

opinion, a Soviet rifle division fielded no more than 7,000 men—an estimate not far off the mark, as it proved; but to assert that Soviet tank armies lacked tanks was nothing but insane self-delusion. Yet this stubborn refusal to face even a modicum of facts enabled Hitler to discount any Soviet attack in the east for the immediate future, whatever Gehlen might indicate to the contrary. Predictably, Himmler held to the same view out of the conviction that the

Führer

could do no wrong nor even think it; a line of thought which scarcely applied to Jodl, who was no

military ignoramus, though he too clung to the idea of persisting with the German attack in the west, whatever the consequences for Germany’s eastern frontier and the vulnerable eastern provinces. None of Guderian’s pleading could deflect Hitler, who was already contemplating yet another blow at the Anglo-American armies—Operation

Nordwind

, designed to recover Alsace.

Yet for all this obsession with the offensive in the west and the quest for ‘the decision’, Hitler perforce threw more than a backward glance at the eastern front, forced to do so by the Soviet pressure in Hungary. Throughout November Malinovskii’s 2nd Ukrainian Front kept up its slogging attacks, fighting its way to the north of Budapest by the end of the month only to become snagged in the Matra hills to the north-east of the Hungarian capital. Once again Malinovskii broke off his offensive. Meanwhile Tolbukhin’s 3rd Ukrainian Front, which had begun its crossing to the western bank of the Danube in the Mohacs–Batina–Apatin area during the first week in November, was slowly fighting its way out of its hard-won bridgeheads, though the sodden ground badly hampered the Russians and their attacks were not helped by the piecemeal manner in which Tolbukhin deployed his forces. Only towards the end of November did Tolbukhin commit substantial forces to the Batina and Apatin Bridgeheads, reinforcement which finally altered the situation and enabled Soviet units to break out in a drive towards lake Balaton and lake Velencze (situated roughly halfway between the northern tip of lake Balaton and the Danube).

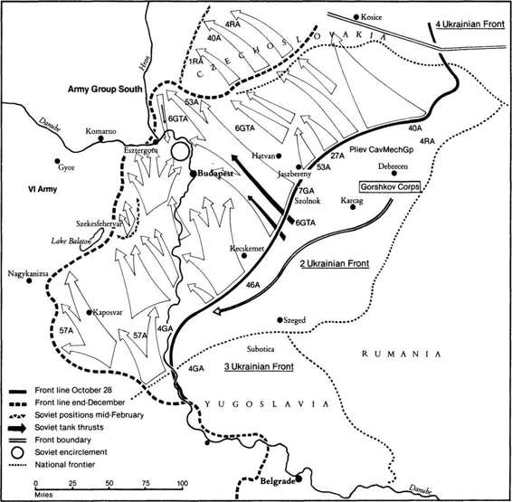

While Tolbukhin moved up from the south-west, Malinovskii on 5 December launched his armies in a brief but powerful thrust designed to cut a path into Budapest from the north-west: Shumilov’s 7th Guards Army was to attack from north-west of Hatvan, with Kravchenko’s 6th Guards Tank Army and Pliev’s ‘mobile group’ following through to the north-east of Budapest; while 53rd Army advanced on Sezcen and 46th Army made for Csepel island, thus outflanking Budapest from the south-west. Tolbukhin’s part in this preliminary manoeuvre consisted of pushing on from his own Danube bridgehead in two directions—towards Szkesfehervar with 4th Guards Army, 18th Tank Corps and Gorshkov’s cavalry corps, and towards Nagykanizsa with 57th Army. This double thrust to the west and the north by Tolbukhin was designed to confuse the German command, who might well assume that the main Soviet objective on the left was to drive on to Austria in the ‘gap’ between the Drava and lake Balaton; the northerly drive into the area of lake Velencze would nevertheless bring 3rd Ukrainian Front to within some thirty miles of Budapest.

On the morning of 5 December, under cover of a 45-minute artillery barrage, Malinovskii’s 2nd Ukrainian Front renewed its attack on Budapest, with Shumilov’s 7th Guards in the lead, striking at the junction between the Sixth and Eighth German Armies. For a week Shumilov’s infantrymen and Kravchenko’s tanks fought their way across the ditches and canals, steadily outflanking Budapest to the north and severing every road linking the Hungarian capital with the northern industrial region. Advancing along the boundary line between the two German

armies Soviet armour made for Vac, a strongly fortified point of great importance in the bend of the Danube which ran to the north of Budapest. The drive on Vac, secured by the capture of Nagyszal and the Tepekh hills (separating the valley of the Danube from that of the rivel Ipel), was the first stage of the operation aimed at the complete encirclement of Budapest, for to the south-east troops of the 46th Army began forcing the Danube just before midnight on 4 December. By morning eleven Soviet rifle battalions were across and rapidly expanding the bridgehead, though frequent German counter-attacks tried to hold this Soviet passage of the Danube in the Ercsi region. On 9 December rifle units of the 46th Army cleared Ercsi, and in the area of lake Velencze linked up with the lead elements of 3rd Ukrainian Front. On the previous day Tolbukhin’s divisions had cleared German troops from the southern edge of lake Balaton and driven to the outskirts of Szekesfehervar and Nagykanizsa; by the evening, 4th Guards Army was approaching the German defence line between lakes Balaton and Velencze, with the left-flank units closing on the south-eastern shore of lake Velencze to link up with Malinovskii’s 46th Army from 2nd Ukrainian Front. On Tolbukhin’s extreme left flank, 57th Army pushed on to the southern shore of lake Balaton and also swept south-westwards to the Drava, seizing a bridgehead on the western bank at Bares.

Shlemin’s 46th Army, fighting its way south of Budapest, inevitably suffered heavy losses. To complete the ‘western encirclement’ with only one weakened army was obviously impossible, and on 12 December the

Stavka

intervened with a revised directive assigning this task to the right flank of Tolbukhin’s 3rd Ukrainian Front, to which 46th Army was transferred (its sector being taken over by the 18th Independent Guards Rifle Corps from Malinovskii’s reserve.) The same

Stavka

directive also prescribed the form that the Soviet encirclement operation must now take: Malinovskii’s 2nd Ukrainian Front (with twenty-eight rifle divisions, six mobile cavalry, armoured and mechanized corps plus some fifteen Rumanian divisions) received formal orders to hold the enemy garrison in Pest on the eastern bank of the Danube as the northerly encirclement drive continued, cutting off the German escape route to the north-west; while Tolbukhin’s 3rd Ukrainian Front with some thirty rifle divisions and four mobile corps was to strike northwards from lake Velencze in the direction of Bicske, to reach the southern bank of the Danube in the area of Esztergom, thereby severing the German escape route to the west. Part of Tolbukhin’s Front was also to attack directly from Bicske towards Budapest, co-operating with Malinovskii’s 2nd Ukrainian Front in seizing the Hungarian capital. The two armies on Malinovskii’s right flank (40th and 27th, together with one Rumanian army) were detached from the battle for Budapest, receiving orders to make a wide outflanking movement to the north in order to cross the old Hungarian–Czechoslovak frontier, advancing to the slopes of the Lower Tatra mountains and further to the south-west, as far as the river Nitra.

Map 13

The Budapest operation, October 1944–February 1945

Malinovskii planned to use 53rd, 7th Guards and 6th Tank Armies in the attack directed against Vac and the northerly bend of the Danube, concentric attacks aimed to the north-west, west and south-west and designed to encircle Budapest completely in co-operation with Tolbukhin’s 3rd Ukrainian. By the evening of 23 December 1944 three corps must be in possession of Pest itself. The right-flank armies, driving into Slovakia and on to the river Nitra, were to make for the route leading from the Moravian Gap to Budapest; in co-operation with Pliev’s ‘mobile group’ advancing from the area of Komarno, this Soviet

force was to aim for Bratislava. Tolbukhin with 3rd Ukrainian Front intended to pierce the ‘Margareten line’ (German defensive positions running from lake Balaton to Hatvan) on two narrow sectors to the east and west of lake Velencze. Once through these defences, Tolbukhin’s armies would co-operate with Malinovskii in closing the ring round Budapest, with 46th Army forming the inner encirclement line and the outer line established by thrusts to the west and north-west.

Behind the lines, in Soviet-occupied Hungarian territory, Stalin hurried ahead with setting up a new Hungarian government, although his plan to rush it into a newly captured Budapest had misfired badly in October. At the end of that month the exiled Hungarian communists—several of them survivors of the first ‘Soviet republic’ in Hungary, many others men who had fled to the USSR in the inter-war period—returned in the baggage train of the Red Army, together with officers of the

NKVD

and the usual complement of former prisoners of war now converted to a new political creed. For the moment this proto-government had to be content with the cramped quarters of Szeged rather than the splendours of Budapest, but the ‘Szeged centre’ soon began to operate, making contact with the organizers of the Hungarian resistance movement and with other potential sympathizers in eastern Hungary. The Hungarian communists received the ready assistance of the Soviet authorities in building up the party organization, though precisely because current policy demanded the creation of the ‘Popular Front’, which required the presence of other parties and the creation of a democratic coalition, the same groups of agitators and organizers helped to stimulate other political bodies—the Social Democrat Party and the Small Farmers Party, with a smaller agrarian ginger-group in the National Peasant Party. This four-party system formed the basis of the Hungarian National Liberation Front. Local ‘national committees’ sprouted in villages and towns, with communist influence predominant in many, but in the beginning the Communists did not find the other parties—and in particular the National Peasant Party—the pliable instruments they had hoped for.