The Roughest Riders (7 page)

Read The Roughest Riders Online

Authors: Jerome Tuccille

The Spanish troops stationed in Cuba included 150,000 regulars and more than 40,000 volunteers, all there in opposition to only about 50,000 Cuban revolutionaries. The US Army originally counted a little more than 27,000 men and 2,000 officers, only a handful of whom were black. On April 22, Congress had passed the Mobilization Act, allowing for an increase in wartime army strength up to 200,000, plus a regular standing army of 65,000. Three days later, McKinley issued his call for 125,000 volunteers to man the campaign in Cuba.

The black soldiers stayed in Chickamauga Park for a few weeks in March and April, pitching tents, chopping wood, lighting campfires, cleaning equipment, drilling under the punishing sun, and losing a baseball game against a team of white soldiers before five thousand spectators. In the beginning, the sojourn in Georgia passed well, according to Theophilus G. Steward, chaplain of the Twenty-Fifth, who said he was pleased to see the fraternity that characterized the relationship between white and black servicemen. He noted in particular that an atmosphere close to friendship prevailed between the black Twenty-Fifth and the white Twelfth.

“Our camp life at Chickamauga Park was one round of pleasure,” wrote John E. Lewis, a trooper with the Tenth. He reported that although white Southerners often tried to stir up trouble

between the white and black soldiers, sometimes it backfired, as in one case when a white soldier objected to the verbal abuse being showered on one of his black comrades by a local white, and he responded by punching out the white civilian. The fight became ferocious and ended in the death of the white Southerner, an act that went unpunished by local authorities. Up to that time, this was one of few instances in the history of American race relations when blacks and whites stood together as one against white racism at large. Before Chickamauga, many of the black soldiers had never been befriended or treated as equals by white men in uniform.

The white press, however, proved less generous. The southern newspapers launched a campaign of malicious abuse against the armed black troops in their community and complained almost daily about their uncivilized conduct. The black soldiers in Chickamauga withstood the insults, backed for the most part by their fellow soldiers, who attributed the hostility to the “well-known prejudices of the Southern people.” As a result, the onslaught of press abuse carried little weight with the men, and in short order, the brouhaha subsided and the black contingents in Georgia were ordered to pack up and get ready to assemble in Tampa, Florida, the next step along the path that would take them to the killing zones in Cuba.

At the end of April, the black troops sent their heavy luggage into storage, shipping off to war with only the equipment deemed essential for combat. They assembled on the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, established by Congress in 1890 to commemorate a Civil War battle, and then headed deeper into the South, toward the even greater swampland of racial animosity around Tampa.

T

ampa at the time was “a BUM place,” according to a white volunteer, First Sergeant Henry A. Dobson, who left a cache of letters describing his experience there. Two railroads linked Tampaâdescribed by one reporter at the time as “a desolate village filled with derelict wooden houses drifting on an ocean of sand”âto Georgia, Louisiana, and other states to the north. The major edifice in town was the Tampa Bay Hotel, grotesquely out of place with its silver minarets and wide porches set amid an arid wasteland of sand, pines, palmettoes, industrial plants, and squalid houses. A few substantial homes for a handful of richer residents, who were a tiny minority of the town's fourteen thousand citizens, stood apart from the others. During the first two weeks of May 1898, more than four thousand black troops descended on this military staging area of “congestion and confusion,” which had been chosen as the one best suited for embarkation to Cuba, wrote historian Karl Grimser.

The words

chaos

and

confusion

inadequately described the prevailing atmosphere in the region. Commanding General William R. Shafter and his sizable staff of officers were hard-pressed to instill discipline and order over the troops pouring into town. Soldiers of

the Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Fifth pitched their tents in Tampa Heights, west of Ybor City on the banks of the Hillsborough River, and the Ninth found space nearby. By the time the Tenth arrived, the campsites were so crowded that the unit had to set up in Lakeland, east of Tampa, alongside a few white units. With the tent poles barely in place, the sight of so many armed black men in town sent shockwaves rippling throughout the community.

The

Tampa Morning Tribune

was quick to fan the fires of hatred and resentment. “The colored infantrymen stationed in Tampa and vicinity have made themselves very offensive to the people of the city,” the newspaper reported. “The men insist upon being treated as white men are treated[,] and the citizens will not make any distinction between the colored troops and the colored civilians.” The press gave front-page coverage to every incident involving black soldiers, reporting daily about “rackets” and “riots” caused by “these black ruffians in uniform.”

“Here in Lakeland we struck the hotbed of the rebels,” wrote John E. Lewis. He described Lakeland as a beautiful little town with a population of about fifteen hundred residents, mostly farmers and country people. The town was surrounded by beautiful lakes, but they stood in counterpoint to the viciousness of the locals, who terrorized the black troops as soon as they arrived, turning the weeks before the war into a hell at home for them. The soldiers encamped there had to watch over their shoulders at all times and be constantly on the lookout for signs of mob violence. Every time a black soldier crossed the line or committed so much as a minor crime, local whites were ready to inflict summary justice on them. Any African American would suffice for a victim, whether or not he was the guilty party.

After making camp, one party of black soldiers entered a drugstore to buy some soda and was subjected to a torrent of abuse from the druggist, who refused to serve them, telling them to take their

money elsewhere. The men were enraged, and the heated emotions were further inflamed when a white barber named Abe Collins came into the store, called them one racial epithet after another, and told them to get the hell out of there or he'd have them strung up. The barber turned on his heels, went back to his barbershop, got his pistols, and returned to the drugstore waving the guns. The soldiers never gave Collins a chance to use them. They pulled their own pistols, and five shots rang out. One of them struck the barber, who fell dead to the floor. The cops showed up quickly after that, arresting two of the soldiers and disarming the rest. Fortunately, that was the end of the action, as the black troops had put the local whites on notice that here was a different breed of men than they had seen before.

But the newspapers would not let the matter die completely. They continued to play on the fears of racist locals, who demanded greater police protection against these armed invaders with “criminal proclivities.” At the same time, they largely ignored the fights and wild behavior by the white soldiers camped throughout the area. “Prejudice reigns supreme here against the colored troops,” a black infantryman wrote to a friend in Baltimore. Everything the African American soldiers did was chronicled disproportionately, attributed in some cases to black brazenness and criminality. White drunkenness scarcely rated a mention in the dailies, but the press excoriated black men who dared look for a drink in white-only saloons. They were also accused of trying to foment riots among law-abiding citizens, who appealed to General Shafter to protect “respectable white citizens” from the black outlaws.

Soon, fistfights erupted between black and white soldiers, who would shortly be fighting side by side against America's common enemy. Reports of dissention among the troops traveled into the North, and Philadelphia sent a committee to Tampa to investigate. Almost predictably, the team of officials blamed the outbreaks of

violence on “the insolence of the Negroes” who were trying “to run Tampa.” Black frustration became incendiary when more and more saloons and cafés refused to serve them. “We don't deal with colored people,” one merchant was quoted. “We don't sell to damned niggers.”

Captain John Bigelow, a sympathetic white officer in a black regiment, came to his soldiers' defense, writing later that if whites had treated the black soldiers with more civility, however much they might discriminate against them, the violence could have been averted.

It all came to a boil on the very eve of the troops' departure for Cuba. Fired up with alcohol, a white Ohio volunteer thought it would be great fun to snatch a two-year-old black child from his mother, hang him upside down with one hand, and spank him with the other. His comrades joined in on the evening's entertainment by demonstrating their marksmanship. With the boy's mother wailing helplessly, the soldiers took turns firing their pistols at the boy to see who could wing a bullet closest to him without actually hitting him. The winner was a white soldier who ripped a hole in a sleeve of the boy's shirt, missing his skin by less than an inch. At the end of the contest, the Ohioans handed the child back to his weeping mother and headed back toward their tents.

Word of the outrage flared like wildfire through the black campsites. Totally fed up with the hostility they had faced in Tampa, the troops of the Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Fifth stormed through town, firing their weapons into the air and charging through the white-only saloons and brothels, tearing the establishments apart as they took on all comers, civilians and soldiers alike. The combined forces of the camp guards and Tampa police were unable to quell the riot. Finally, the commanding general assigned the job of restoring peace to the all-white Second Georgia Volunteer Infantry. They waded in with fixed bayonets, loaded guns, and heavy

truncheons, and battled with the black troops through the wee hours of the morning. Near daybreak on the morning of June 7, the Georgia volunteers had accomplished their mission.

In an attempt to cover up the extent of the mayhem, the official report stated that no one had been killed in the incident. Local newspapers claimed that twenty-seven black soldiers and a handful of whites had sustained serious enough injuries for them to be transported to Fort McPherson, in East Point, Georgia, on the southwest edge of Atlanta. The black press, however, viewed the melee differently, reporting that the streets of Tampa “ran red with Negro blood” and “many Afro-Americans were killed and scores wounded.” Howard Zinn wondered in his 1980 book

A People's History of the United States

why the black troops maintained their loyalty to their country in the face of such rampant racism. Many black American soldiers began to question that sort of lopsided loyalty themselves. In the four years between 1889 and 1902, black troops wrote 114 letters to black newspapers complaining about the way they were treated by their fellow countrymen.

For once, the

Tampa Morning Tribune

played down the publicity given to the black soldiers involved in the riot, believing that if the true facts got out, they would reflect adversely on the city. The newspaper's chamber-of-commerce mentality won out over snarling racial bigotry, for the moment at least.

T

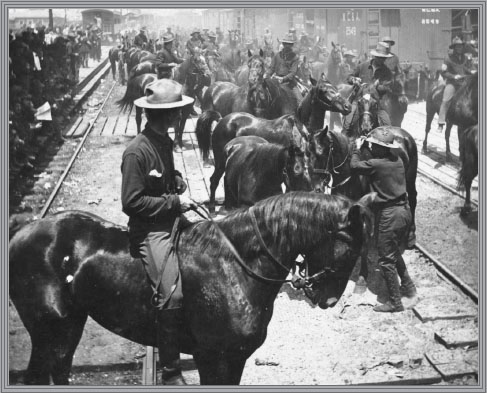

eddy Roosevelt and the First United States Volunteer Cavalry left San Antonio bound for Tampa on May 29. His seven trainloads of troops, mules, horses, and a mountain lion cubâwith up to eighteen cars in each trainâmade great fodder for the press as they passed almost twelve hundred miles through the heart of the South. Cheering multitudes greeted them at almost every stop, where they restocked their supplies, sometimes roping chickens, pigs, and virtually everything else that was edible, hauling them up through the train windows and cooking them on the floors. Roosevelt had gathered around him an eccentric collection of men who were accustomed to the use of firearms and to fending for themselves in nature, he said. The future president wrote that the men he picked were “intelligent and self-reliant; they possessed hardihood and endurance and physical prowess.”

When they arrived in Tampa on June 3 to what was described as “an appalling spectacle of congestion and confusion,” the only people surprised that there was no one on hand to meet them and tell them where to camp were Roosevelt and his men. Worst of all,

there was no food set aside for them. Roosevelt and his officers made the rounds of local merchants and used their own money to restock their supplies. Then they confiscated some abandoned wagons to transport their food and luggage to a campground a little more than a mile west of the Tampa Bay Hotel, near the present-day intersection of Armenia Avenue and Kennedy Boulevard. By noon, they had pitched their tents in long, straight rows alongside those of the Second, Third, and Fifth Cavalry divisions, with the officers' quarters on one end and a kitchen on the opposite end. Roosevelt lost no time ordering his men onto an open field to begin marching

drills, followed by cavalry drills a day later when their horses were sufficiently rested.