The Roughest Riders (8 page)

Read The Roughest Riders Online

Authors: Jerome Tuccille

Tampa was chaotic in May 1898 when the Rough Riders finally arrived after their long journey from San Antonio. Roosevelt and his fellow officers had to spend their own money to buy food and supplies for the troops.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (LC-DIG-stereo-1s01904)

With his men hunkered down awaiting orders to debark for Cuba, Roosevelt set up his headquarters at the Tampa Bay Hotel, where his friend Colonel Wood allowed him to spend the night, from the dinner hour until breakfast the following morning. General Shafter dispensed $175,000 to pay the men the money due to them for their service, and they immediately set out for Ybor City and other areas in the middle of town for a night of carousing. The Rough Riders in their brown canvas uniforms and wide-brimmed gray hats stood out from their fellow soldiers dressed in traditional dark blue shirts and trousers.

Shafter and the other senior officers debated strategy at the hotel before sailing for Cuba. One of the first orders of business was deciding where to land on the Cuban coast. Shafter at first believed they would go ashore somewhere around Matanzas or Cardenas, east of Havana on the northern side of the island. Shafter insisted that an American victory would require upward of five thousand American troops, who would join forces with twenty-five thousand Cuban rebels to battle the Spanish soldiers, which he was convinced numbered no more than fifty thousand scattered throughout the island. With that number of troops under his command, plus a concentrated naval bombardment on the city of Havana, Shafter thought the conquest of Cuba would be a simple affair.

In retrospect, the general's assessment of the challenges he faced proved to be ludicrous. What he thought would be accomplished in a few months with so few soldiersâto say nothing of the dangers incurred by striking directly at Havanaâfell far short of the terrible reality.

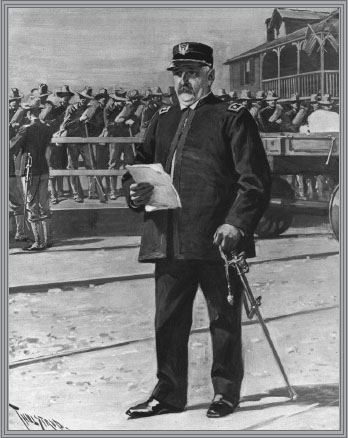

General William R. Shafter, well past his prime and hobbled by obesity and gout, is generally believed to have botched the disembarkation from Tampa, which was a bedlam of chaos and confusion.

Commons.Wikimedia.Org

The soldiers jammed into the bars, brothels, and gambling houses with pockets full of cash to spend. Fights broke out among Roosevelt's troops and regular army soldiers, and when they got tired of pounding on one another, they ransacked local homes, beat up the town cops, invaded a British ship in the harbor, and stole bananas, coconuts, and booze. Children followed the Rough Riders through the streets as they drank, laughed, fought, and rampaged at will. Some of the local youth made cardboard spurs, which they taped

onto their shoes in imitation of Roosevelt's curious collection of cowboys, ranchers, former sheriffs, gunfighters, some Eastern blue-bloods, and a handful of Native Americans. The Easterners were mostly wealthy university kids looking for adventure, among them Hamilton Fish, grandson of President Ulysses S. Grant's secretary of state. More typical were the rough-and-tumble Westerners like former Dodge City marshal Benjamin Daniels, who had had half his ear chewed off during a barroom brawl. Most of them had never seen so much water before, let alone saltwater, and were disappointed to learn they couldn't drink it.

Their sojourn in Tampa lasted only a few days. President McKinley, feverishly following developments in Cuba from his war room on the second floor of the White House, surrounded by an array of maps and fifteen telephones, sent word that the troops should prepare to depart toward the eastern coastline of Cubaânot the northern coastâwhere the rebels maintained a strong presence. He assembled a fleet of transport ships beyond a narrow stretch of land bordering the dredged canal in Port Tampa. He then ordered General Shafter to begin shifting men and material along the single nine-mile track connecting the campsites around the city to the ships in the harborâan ordeal that lasted almost two weeks.

Roosevelt's Rough Riders were devastated when they learned that they would have to leave their beloved horses behind, except for six horses per regiment for the officers. On the first sailing, there was only enough room aboard the fleet for essential supplies, pack mules, the small number of horses, and eight troops of seventy men. The allowance for the officers' baggage was reduced from 250 to 80 pounds. Navy secretary Long, however, convinced the president that such a small armada would easily be destroyed by the Spanish fleet under the command of Vice Admiral Pascual Cervera, which could intercept them before they reached Cuba. Cervera was said to be heading toward Cuba with fresh troops, arms, and supplies.

The United States' North Atlantic Squadron, commanded by William T. Sampson, by then promoted to Rear Admiral, was entrusted with blockading the Cuban ports. McKinley countermanded his original instructions and dispatched orders to board the entire expedition simultaneously, triggering a frantic twenty-four-hour rush to get everyone ready to leave as quickly as possible. As it turned out, the transport ships could carry only about sixteen thousand men, rather than the twenty-five thousand authorized for service in Cuba, and Roosevelt was informed he could take with him only 560 of his Rough Riders, roughly half of the men who had signed up. The rest had to remain behind in Tampa. The American fleet was to depart at daybreak on June 8. Anyone not aboard by then would be left behind.

Roosevelt was furious at the bungled operation, mismanaged from the start before they even got under way. He and his entire group of Rough Riders were in danger of missing out on the action altogether when a train scheduled to pick them up at midnight failed to arrive.

“We were ordered to be at a certain track with all our baggage at midnight,” Roosevelt wrote, “there to take a train for Port Tampa.” The Rough Riders were there at midnight, but the train never showed up. The men crashed along the sides of the tracks, trying to get some sleep, while Wood, Roosevelt, and a few other officers looked for someoneâanyoneâwith information about what they should do. Every so often they came across a general or two, none of whom knew any more than they did. Other regiments had already boarded trains, only to remain stationary on the tracks when the cars failed to get moving.

At three o'clock in the morning, Wood got a message telling him to hike his men over to a different set of tracks, where a train would be waiting for them. Again, no such train was in evidence. Finally, at six in the morning, Roosevelt and the Rough Riders

decided to take matters into their own hands. They commandeered an empty coal train with long flatcars and ordered the engineer to get them on their way to Port Tampa. They simply stopped the train and hopped on board, startling the unsuspecting engineer. Wood and Roosevelt convinced the befuddled gentleman to start backing down the track westward, until they reached the end of the line at the coast in Port Tampa, almost ten miles away.

Just as daylight was breaking over the eastern horizon, the train chugged into the so-called Last Chance Village, a makeshift town or staging area containing bars, brothels, and women cooking chicken on Cuban clay stoves. The locale was aptly named, as it was the last chance for the men to load up on a decent meal, beer, or whiskey, and a girl if time allowed. Roosevelt and his men were grimy with soot and coal dust, but their entire unit and equipment were intact. They stepped off the flatcars into the chaos of the harbor, staring in alarm at the thousands of men who had beaten them there and were struggling to scamper onto the ships in time.

More confusion ensued when they looked out at the flotilla of thirty-one ships and realized they had no instructions about which one was assigned to them. Roosevelt tracked down Colonel Charles Frederic Humphrey, the overwhelmed officer in charge of loading operations, who told Roosevelt to take a launch out to the

Yucatan

, which was anchored off the dock. Roosevelt mustered his men, and together they outmaneuvered two other regiments also anxious to board the ship, which was quickly filled to capacity. Roosevelt managed to get two of his horses, Rain in the Face and Texas, on board as well.

And there they remained for a week, the entire expedition that was supposed to leave at dawn, sweltering beneath the blistering Florida sun, chowing down on bad foodâincluding so-called corned beef, which the men called “embalmed meat”âfuming inwardly over the hopelessly crowded conditions aboard ship and

boiling to get into action as they waited for orders to sail. On the evening of June 13, they finally received word to get ready to depart from their US homeland the next morning and head down the coast of Florida toward war in Cuba.

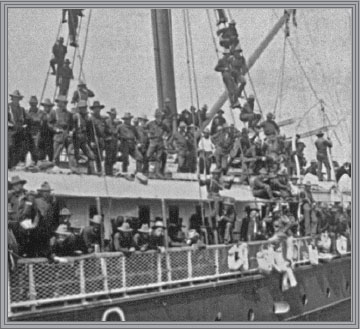

When Roosevelt discovered that no ship had been assigned to the Rough Riders to transport them to Cuba, he outmaneuvered two other regiments to get his men on board the already overcrowded

Yucatan.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (LC-USZ62-57122)

T

he black regiments, along with a small group of white soldiers, were assigned to six ships: the

Miami

,

Alamo

,

Comal

,

Concho

,

City of Washington

, and

Leona.

They were sent down to the lowest deck, where no light could penetrate the dark enclosure beyond the ten feet from the main hatch. The bunks were stacked in four tiers and lined up so closely together that the men could barely slip between them. They were constructed of raw timber, with rectangular rims four to six inches high. There was no bedding except for whatever the men could improvise for themselves, using blankets for mattresses and haversacks for pillows. The men were forced to stack their gear, including their clothes, shelter-halves, rifles, and ammunition, on their bunks, allowing them scarcely enough room to stretch out and sleep. Toilet and bathing facilities were all but nonexistent. The lowest deck of the

Concho

contained a single toilet for more than twelve hundred soldiers.

Adding insult to injury, the black troops were confined aboard ship during the time they were in port, while their white brethren were allowed to visit the bars, brothels, and cafés in Last Chance Village whenever they pleased. They crowded onto the upper decks

to find sunlight and breathe fresh air as often as they could, but they seethed over the ongoing racism they were subjected to, even as they prepared to risk their lives in war on foreign soil.

Sergeant Major Frank W. Pullen of the Twenty-Fifth said that the black troops on board were not allowed to “intermingle” with the whites. “We were put on board,” he said, “but it is simply because we cannot use the term

under board.

We were huddled together below two other regiments and under the water line, in the dirtiest, closest, most sickening place imaginable. For about fifteen days we were on the water in this dirty hole, but being soldiers we were compelled to accept this without a murmur.” They ate corned beef, canned tomatoes, and hardtack until they were almost sickened by it, but it was the only food available for them.

Their anger reached a boiling point when their officers ordered them to let the white regiments make coffee and eat their meals first, before the black troops could assuage their own hunger. Pullen said it was a miracle they managed to live through those days aboard ship in the harbor under such horrendous conditions. They swallowed their pride and accepted their fate without exploding in violence, a tribute to the collective self-discipline they displayed.