Read The Secret Life of Salvador Dali Online

Authors: Salvador Dali

The Secret Life of Salvador Dali (41 page)

One evening I was the victim of the confidences of an artist who expressed the most complete admiration for my work. Naïvely and without the slightest reticence, he poured out his heart to me, revealing in the details of his story a case of spiritual poverty which rivalled his pecuniary poverty. He seemed to believe that after having told his story he would be able to achieve, if not a perfect communion of souls, at least a communication of ideas, an interchange of feelings which might not perhaps bring much light to his troubled spirit but which would at least console him, through my comprehension of his multiple torments, and that if my commiseration became propitious, he might even ask me for a little financial aid.

“Well,” he said, when he came at last to the end of his story, with tears in his eyes and depressed by my long and expressionless silence, “that’s how it is with me! How is it with you?”

“With me? I command a very high price,” I answered slowly, and as I did so I was looking across at one of the towers of the Palace of Communications in which I remember that a window opened at that very moment, letting fall from its height a whitish object which I watched as it fell.

Receiving no answer to my remark I turned my head to look at the man. His face was hidden in a dubiously clean handkerchief and he was weeping. I had sacrificed him! Yet another victim to the growing dandyism of my mind. I felt a burst of pity, and was about to make a move toward him and console him in a brotherly way. But the esthetics of my attitude commanded me to act in just the opposite way. To make matters worse, the wretched state of his person communicated to me a physical repugnance which would have cut short any attempt at a warm effusion.

I said to him then, after having placed a friendly hand on one of his sunken shoulders, covered with dandruff from his rat’s hair,

“Why don’t you try to hang yourself?... Or throw yourself from the top of a tower?”

And as I left him standing there I thought of that whitish bundle that had just fallen from one of the windows of the Palace of Communications. Was it Maldoror?

1

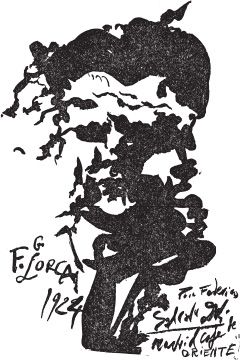

The shadow of Maldoror hovered over my

life, and it was just at this period that for the duration of an eclipse precisely another shadow, that of Federico Garcia Lorca, came and darkened the virginal originality of my spirit and of my flesh.

During this time I knew several elegant women on whom my hateful cynicism desperately grazed for moral and erotic fodder. I avoided Lorca and the group, which grew to be his group more and more. This was the culminating moment of his irresistible personal influence—and the only moment in my life when I thought I glimpsed the torture that jealousy can be. Sometimes we would be walking, the whole group of us, along El Paseo de la Castellana on our way to the cafe where we held our usual literary meetings and where I knew Lorca would shine like a mad and fiery diamond. Suddenly I would set off at a run, and no one would see me for three days... No one has ever been able to tear from me the secret of these flights, and I don’t intend to unveil it now—at least not yet...

I shall only tell you that one of my favorite games at this time was to dip bank notes into my whiskey until they began to disintegrate. This involved a long ceremonial which would dumfound those who happened to witness it. I loved to practice this trick while I argued, with a refined avarice, about the price of one of those modest

demi-mondaines

who offer themselves to you body and soul, saying “Give me whatever you like!”

At the end of a year of libertinism I received notice of my permanent expulsion from the Academy of Fine Arts. This time the matter appeared in an official announcement in

La Gaceta

, as an order signed by the king, on October 20th, 1926. The story of this incident has been faithfully reported

in one of the anecdotes which I have chosen for my anecdotic self-portrait.

This time my “expulsion” in no way astonished me. Any committee of professors, in any country in the world, would have done the same on feeling themselves thus insulted. The motives for my action were simple: I wanted to have done with the School of Fine Arts and with the orgiastic life of Madrid once and for all; I wanted to be forced to escape all that and come back to Figueras to work for a year, after which I would try to convince my father that my studies should be continued in Paris. Once there, with the work that I would bring, I would definitely seize power!

But before leaving Madrid I wanted to savor that last evening alone. I ambled through hundreds of streets that I had never seen. In one afternoon I squeezed out to the last drop the whole substance of that city, where the people, the aristocracy and pre-history know no transition. It shone beneath the concise and limpid October light, like an immense peeled bone faintly tinted with blood-pink. In the evening I went and sat down in my favorite corner of the Rector’s Club, and contrary to my habit I drank just two sober whiskeys. Nevertheless I was one of the last to leave, and I was assailed by a trembling little old woman in rags who persecuted me with her insistent begging. I paid no attention to her and continued on my way. When I got as far as the Bank of Spain, with the beggar-woman still trailing me, I ran into a very beautiful young woman who offered me gardenias. I gave her a hundred pesetas and took all she had. Then, turning round, I made a present of them to the old beggar-woman. She remained for a long time glued to the spot like a statue of salt. I walked on slowly for several minutes, and when I again turned round I could barely make out in the moonlight a little black mass with a white smudge in the middle which was all I could see of the basket filled with flowers which I had left in her hands—hands gnarled like vine-stalks and covered with sores.

The following day I was too lazy to pack my suitcases, and left with all my luggage empty. My arrival in Figueras caused a general consternation in my family: expelled, and without even a clean shirt to change into! Good heavens, what would happen to my future! To console them all, I kept telling them,

“I swear to you I was convinced I had packed all my suitcases, but I must have confused it with the last time”—I was referring to my return home two years before.

On my arrival in Figueras I found my father thunderstruck by the catastrophe of my expulsion, which had shattered all his hopes that I might succeed in an official career. With my sister, he posed for a pencil drawing which was one of my most successful of this period. In the expression of my father’s face can be seen the mark of the pathetic bitterness which my expulsion from the Academy had produced on him.

At the same time that I was doing these more and more rigorous

drawings, I executed a series of mythological paintings in which I tried to draw positive conclusions from my cubist experience by linking its lesson of geometric order to the eternal principles of tradition. I took part in several collective expositions in Madrid and in Barcelona, and had a one-man exposition in the Gallery of Dalmau, who was the Barcelonian patriarch of advance-guardism and who looked as though he might have just stepped out of a painting by El Greco.

All this activity, which I carried on without stirring from my studio in Figueras for one second, produced a profound commotion, and the polemics aroused by my works reached the attentive ears of Paris. Picasso had seen my

Girl’s Back

in Barcelona, and praised it. I received on this subject a letter from Paul Rosenberg asking for photographs, which I failed to send, out of sheer negligence. I knew that the day I arrived in Paris I would put them all in my bag with one sweep. One day I received a telegram from Juan Miro, who at this period was already quite famous in Paris, announcing that he would come and visit me in Figueras, accompanied by his dealer, Pierre Loeb. This event made quite an impression on my father and began to put him on the path of consenting to my going to Paris some day to make a start. Miro liked my things very much, and generously took me under his protection. Pierre Loeb, on the other hand, remained frankly sceptical before my works. On one occasion, while my sister was talking with Pierre Loeb, Miro took me aside and said in a whisper, squeezing my arm,

“Between you and me, these people of Paris are greater donkeys than we imagine. You’ll see when you get there. It’s not so easy as it seems!”

Before a week was over, in fact, I received a letter from Pierre Loeb in which, instead of offering me a splendid contract as I had thought he would when I received Miro’s telegram, he said something to this effect,

“Do not fail to keep me in touch with your work. But for the moment what you are doing is too confused and lacks personality. You must be patient. Work, work; we must wait for the development of your undeniable gifts. And I hope that some day I shall be able to handle your work.”

Almost at the same time my father received a letter from Juan Miro in which he explained to him the advisability of my coming to spend some time in Paris. And he ended his letter with these very words, “I am absolutely convinced that your son’s future will be brilliant!”

It was at about this period that Luis Bunuel one day outlined to me an idea he had for a motion picture that he wanted to make, for which his mother was going to lend him the money. His idea for a film struck me as extremely mediocre. It was advance-guard in an incredibly naïve sort of way, and the scenario consisted of the editing of a newspaper which became animated, with the visualization of its news-items, comic strips, etc. At the end one saw the newspaper in question tossed on the sidewalk, and swept out into the gutter by a waiter. This ending, so banal and cheap in its sentimentality, revolted me, and I told him that this

film story of his did not have the slightest interest, but that I on the other hand, had just written a very short scenario which had the touch of genius, and which went completely counter to the contemporary cinema.

This was true. The scenario was written. I received a telegram from Bunuel announcing that he was coming to Figueras. He was immediately enthusiastic over my scenario, and we decided to work in collaboration to put it into shape. Together we worked out several secondary ideas, and also the title—it was going to be called

Le Chien Andalou

. Bunuel left, taking with him all the necessary material. He undertook, moreover, to take charge of the directing, the casting, the staging, etc... But some time later I went to Paris myself and was able to keep in close touch with the progress of the film and take part in the directing through conversations we held every evening. Bunuel automatically and without question accepted the slightest of my suggestions; he knew by experience that I was never wrong in such matters.

To go back a little, I spent another two months in Figueras making my last preparations before pouncing on Paris. I have forgotten to mention that before Pierre Loeb’s arrival I had already made a trip to Paris which lasted just a week, in the company of my aunt and my sister. During this brief sojourn I did only three important things. I visited Versailles, the Musée Grevin, and Picasso. I was introduced to the latter by Manuel Angelo Ortiz, a cubist painter of Granada, who followed Picasso’s work to within a centimetre. Ortiz was a friend of Lorca’s and this is how I happened to know him.

When I arrived at Picasso’s on Rue de La Boétie I was as deeply moved and as full of respect as though I were having an audience with the Pope.

“I have come to see you,” I said, “before visiting the Louvre.”

“You’re quite right,” he answered.

I brought a small painting, carefully packed, which was called

The Girl of Figueras

. He looked at it for at least fifteen minutes, and made no comment whatever. After which we went up to the next story, where for two hours Picasso showed me quantities of his paintings. He kept going back and forth, dragging out great canvases which he placed against the easel. Then he went to fetch others among an infinity of canvases stacked in rows against the wall. I could see that he was going to enormous trouble. At each new canvas he cast me a glance filled with a vivacity and an intelligence so violent that it made me tremble. I left without in turn having made the slightest comment.

At the end, on the landing of the stairs, just as I was about to leave we exchanged a glance which meant exactly,

“You get the idea?”

“I get it!”

It was after this ephemeral voyage that I held my second and third exhibits, at the Dalmau Gallery and at the Salon of Iberian Artists of Madrid. These two shows definitely consecrated my popularity in Spain.

Now, then—to return to the point I had reached before I filled in that oversight which I hope will quickly heal in your memory—I am in Figueras and am preparing, as I have already said, to pounce on Paris. During these two months I trained myself, I sharpened all my doctrinal means of action at a distance, and I did so by making use of a small coterie of intellectuals of Barcelona grouped around a review called

The Friend of the Arts

. This group I manipulated as I wished, and used as a convenient platform for revolutionizing the artistic ambiance of Barcelona. I did this all by myself, without stirring from Figueras, and its sole interest for me, naturally, was that of a preliminary experiment before Paris, an experiment that would be useful in giving me an exact sense of the degree of effectiveness of what I already at that time called my “tricks.” These tricks were various, and even contradictory, and were merely terroristic and paralyzing devices for imposing the ferociously authentic essence of my irrepressible ideas, by which I lived and thanks to which my “tricks” not only became dazzlingly effective, but emerged from the category of the episode and became incorporated into that of history. I have always had the gift of manipulating and of dominating with ease the slightest reaction of people who surround me, and it is always a voluptuous pleasure to feel at constant “attention” to my capricious orders all those who, in obeying me to the letter,

2

will most likely go down in to their own purgatory, without even suspecting their faithful and involuntary subordination.