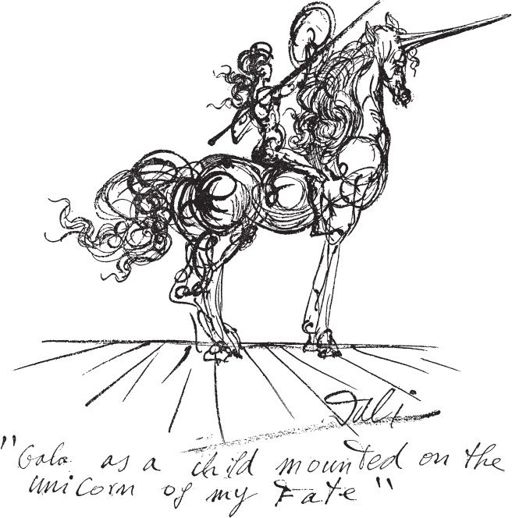

The Secret Life of Salvador Dali (44 page)

Read The Secret Life of Salvador Dali Online

Authors: Salvador Dali

From the moment of my arrival at Cadaques I was assailed by a recrudescence of my childhood period. The six years of the baccalaureate, the three years of Madrid, and the voyage I had just made to Paris—all receded into the background, becoming blotted out until they totally disappeared, whereas all the fantasies and representations of my childhood period again victoriously took possession of my brain. Again I saw passing before my ecstatic and wondering eyes infinite images which I could not localize precisely in time or space but which I knew with certainty that I had seen when I was little. I saw some small deer, all green except for their horns which were sienna-colored. Surely they were reminiscences of decalcomanias. But their contours were so precise that it was easy for me to reproduce them in painting, as though I were copying them from a visual image.

I also saw other more complicated and condensed images: the profile of a rabbit’s head, whose eye also served as the eye of a parrot, which was larger and vividly colored. And the eye served still another head, that of a fish enfolding the other two. This fish I sometimes saw with a grasshopper clinging to its mouth. Another image which often came into my head, especially when I was rowing, was that of a multitude of little parasols of all the colors in the world. I saw this image several times while engaging in other forms of violent exercise. And the multiplicity of colors of all those parasols left with me for the whole rest of the day an impression of ineffable joy.

After some time spent wholly in indulging in this kind of fancy summoned up out of childhood reminiscences, I finally decided to undertake a picture

8

in which I would limit myself exclusively to reproducing each of these images as scrupulously as it was possible for me to do according

to the order and intensity of their impact, and following as a criterion and norm of their arrangement only the most automatic feelings that their sentimental proximity and linking would dictate. And, it goes without saying, there would be no intervention of my own personal taste. I would follow only my pleasure, my most uncontrollably biological desire. This work was one of the most authentic and fundamental to which surrealism could rightly lay claim.

I would awake at sunrise, and without washing or dressing sit down before the easel which stood right beside my bed. Thus the first image I saw on awakening was the painting I had begun, as it was the last I saw in the evening when I retired. And I tried to go to sleep while looking at it fixedly, as though by endeavoring to link it to my sleep I could succeed in not separating myself from it. Sometimes I would awake in the middle of the night and turn on the light to see my painting again for a moment. At times again between slumbers I would observe it in the solitary gay light of the waxing moon. Thus I spent the whole day seated before my easel, my eyes staring fixedly, trying to “see,” like a medium (very much so indeed), the images that would spring up in my imagination. Often I saw these images exactly situated in the painting. Then, at the point commanded by them, I would paint, paint with the hot taste in my mouth that panting hunting dogs must have at the moment when they fasten their teeth into the game killed that very instant by a well-aimed shot.

At times I would wait whole hours without any such images occurring. Then, not painting, I would remain in suspense, holding up one paw, from which the brush hung motionless, ready to pounce again upon the oneiric landscape of my canvas the moment the next explosion of my brain brought a new victim of my imagination bleeding to the ground. Sometimes the explosion occurred and nothing fell. Sometimes I would dash off in a mad and fruitless chase, for what I had thought was a partridge turned out to be just a leaf that the shock of the bullet had shaken from a branch. To win forgiveness for my mistake I came back hanging my head and humiliated myself before my master. Then I would feel the protective fingers of my imagination scratch me reassuringly between my two eyebrows, and I would close my eyes with fawning voluptuousness.

A violent pecking would occur inside my brow, and sometimes I would have to scratch myself with my two hands. One would have said that the colored parasols, the little parrots’ heads and the grasshoppers formed a seething mass just back of the skin, like a gay nest of worms and ants. When the pecking was over, I felt anew the calm severity of Minerva pass the cool hand of intelligence over my brow, and I said to myself, “Let’s go for a swim.” I would climb over the rocks and find a spot completely sheltered from the wind. There I would bask in the stifling heat, waiting till the last moment to dip into the icy water, plunging from the jutting rocks straight down into the Prussian blue

depths, even more unfathomable than those of the Muli de la Torre. My naked body embraced my soul caressingly, and said to it, “Wait—she is coming.” My soul did not like these embraces and tried to elude the too violent impulses of my youth.

“Do not press me so,” said my soul, “you know perfectly well she is coming for you.”

After which my soul, who never bathed, went and sat down in the shade.

“Go—go and play!” she said, exactly as my nurse had done when I was little. “When you are tired come and get me and we will return home.”

In the afternoon, again, bent before my picture, I would paint with my body and soul until there was no more light in my room. The full moon caused the maternal tide of my soul to rise, and shed its insipid light over the very real full-blown feminine body, covered by sheer summer dresses, of the Galuchka of my “false memories” which had continually grown with the years. With all my soul I wanted her. But feeling her to be already very close I now wished the pleasures and tortures of expectation to be further prolonged. And while I yearned for the moment when she would come, more intensely than for anything in the world, I said to myself, “Make the most, make the most of this wonderful occasion. She is not yet here!” And with a delirious delight I dug my nails into each precious moment that remained to me to continue to be alone. Once more I wrenched from my body that familiar solitary pleasure, sweeter than honey, while biting the corner of my pillow lighted by a moonbeam, sinking my teeth into it till they cut through the saliva-drenched fabric. “Ay, ay!” cried my soul. After which I went to sleep beside her without daring to touch her.

She always awoke before I did, and when at sunrise I opened my eyes I found her already up standing beside my picture, watching. Did she never sleep?

I excuse myself for the crudeness I am about to commit by stating that everything I have just been saying about my “soul” is allegorical. But it was a familiar allegory, which occupied a quite definite place in my fantasies of that time. I make this remark because the story that I am about to tell, far from being an allegory, constitutes a true “hallucination,” the only one I have experienced in my life, and for this very reason it is necessary that I tell it scrupulously, while taking precautions lest it be confused with the rest of my fantasies or images. These, while sometimes endowed with a great visual intensity, never attain the degree of being hallucinatory.

It was on a Sunday, and as usual on that day I got up very late. It must have been about half past twelve. I was awakened by an immediate urge to relieve myself. I got up and went to the bathroom, which was down on the second floor. I had a bit of conversation with my father after leaving the toilet, where I had stayed about fifteen minutes, which he himself subsequently confirmed. (This eliminates the possibility that

I may have dreamed that I went down to the bathroom—I was thus awake, and well awake.) I went upstairs again to my room, and barely had I opened the door when I saw sitting before the window, in three-quarter view, a rather tall woman wearing a kind of nightgown. In spite of the “absolute reality” and the normal corporeality of this being, I immediately realized that I was the victim of an hallucination,

9

and contrary to everything I had anticipated I was in no way impressed. I said to myself, “Get back into your bed so that you can observe this astonishing phenomenon completely at your ease.” I got back into bed, but without lying down. However, during the moment that I stopped looking at the apparition to put my two pillows behind my back she disappeared. I did not see her gradually melt away, but when I looked again in her direction she had simply disappeared.

The incontrovertible fact of this apparition made me anticipate the possibility that others would follow. And from this time on, in spite of the fact that it was never repeated, each time I open a door I am aware of the possibility that I may see something that is not normal. In any case I myself at that time “was not normal.” The limits of the normal and the abnormal are perhaps possible to define, and probably impossible to delimit in a living being. But when I say that at this period I was abnormal I mean as compared to the moment I am writing this book. For since the period of which I am speaking I have made bewildering progress in this direction of normality, and in the direction not only of passive but even and especially of active adaptation to reality.

At the time when I had my first and only hallucination I derived satisfaction from each of the phenomena of my growing psychic abnormality, to such a point that everything served to stimulate them. I made desperate efforts to repeat each of these, adding each morning a little fuel to my folly. Later, when I saw the fruits of this folly threatening to clutter up my life, becoming so vigorous that it seemed as though they

might deprive me of all the air I needed, then I rejected folly with violent kicks, and undertook a crusade to recover my “living-space”; and the slogan of this first moment—“The irrational for the sake of the irrational”—was one which I was to transform and canalize at the end of a year into that other slogan, which was already of Catholic essence—“The Conquest of the Irrational.” So that the “Irrational” which, at the moment of which I am speaking, I was treating with all the honors and ceremonials due to a true divinity was a thing which I already completely rejected at the end of a year. And while profiting by the secrets I had torn from it, and which it had yielded to me, during the promiscuity of our relations, I set out with fury, stubbornness and heroism to try to conquer it, destroying it pitilessly as I progressed, and at the same time trying to pull the entire surrealist group along with me.

10

1929. I am, then, in the white-washed Cadaques of my childhood and my adolescence. Grown to manhood, and trying by every possible means to go mad—or rather, doing everything in my conscious power to welcome and help that madness which I felt clearly intended to take up its abode in my spirit. “Ay! Ay!” my soul would cry.

At this point I began to have fits of laughter. I would laugh so much that often I was obliged to lie down on the bed to rest. These fits gave me violent pains in my sides. What did I laugh at? At almost anything. I would imagine, for instance, three tiny curates running very fast in single file across a little Japanese gangplank, like the ones in the Tsarskoe Selo. Just at the moment when the last of the small curates, who was much smaller than the others, was about to leave the gangplank, I would kick him hard in the behind. I saw him stop like a hunted mouse, and take to his legs, recross the gangplank and run off in the opposite direction from that in which the others were going.

The little curate’s terror the moment I kicked him struck me as the most comical thing in the world, and I had only to imagine this scene to myself again to writhe with laughter, unable to stop, to hold myself in, no matter under what circumstances I happened to find myself.

Another example, among innumerable ones of this kind, was that of imagining certain people I knew with a little owl perched on their heads, which in turn carried an excrement on its own head. This owl was carved, and I had imagined it to the minutest detail. The excrement always had to be a bit of my own excrement. But the efficacy of this little excrement-bearing owl was not uniform. It varied according to the individuals on whose heads I tried to balance it by turns in my imagination. For certain ones the comic effect was such as to provoke me to a paroxysm of laughter; for others it was completely inoperative. Then I would remove it from this head and try it on another one. And suddenly I would

find the head, the exact expression of the face to go with my owl. And once it was in place I would contemplate the hilarious, infinite and instantaneous relationship which established itself magically between the face of the person I knew, who was completely unaware of what I had just put on his head, and the fixed stare of the owl balancing his excrement, and which provoked me to such spasmodic explosions of laughter that my family hearing from below the noise I was making wondered, “What’s going on?” “That child laughing again!”

11

my father would say, amused and preoccupied as he watered a skeletal rosebush wilting in the heat.