Read The Shaping of the Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Bernard Lewis

Tags: #History, #Middle East, #General

The Shaping of the Modern Middle East (2 page)

Acknowledgments

The earlier version of this book contained the following note of acknowledgment:

I should like to record my thanks to Indiana University for giving me this opportunity to present my views on this subject, and to my colleagues and students at Bloomington for their gracious and friendly hospitality during the six weeks of my stay. My thanks are also due to my colleagues Dr. S. A. A. Rizvi and Dr. M. E. Yapp, for several helpful suggestions, and to Professor A. T. Hatto and Mr. E. Kedourie for reading and criticizing my typescript. They are of course in no way responsible for any defects that remain. Finally, I would like to thank Professor W. Cantwell Smith and the New American Library of World Literature Inc., for permission to reproduce the passage cited on p. 168, and Simon and Schuster for a quotation from James G. McDonald's My Mission to Israel.

It is now my very pleasant duty to thank my assistant, Jane Baun, for her invaluable help in preparing-and in many different ways, improving-this new edition. I should also like to record my indebtedness to Nancy Lane and Irene Pavitt, of Oxford University Press, for their help and advice in the production of this book. Once again, I offer my thanks to all of them for their many suggestions that I accepted, and my apologies for those that I resisted. From this it will be clear that whatever defects remain are entirely my own.

Contents

1 Sketches for a Historical Portrait

3

4 Patriotism and Nationalism

71

6 The Middle East in International Affairs

125

Notes

165

Index

171

Ct Ct U td U m W4 Q) b U O z

b .. a U

THE SHAPING OF

THE MODERN MIDDLE EAST

1

Sketches for a

Historical Portrait

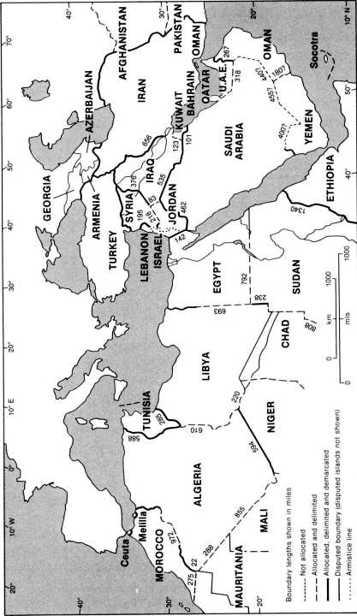

The term "Middle East" was invented in 1902 by the American naval historian Alfred Thayer Mahan, to designate the area between Arabia and India, with its center-from the point of view of the naval strategist-in the Persian Gulf. This new geographical expression was taken up by The Times (of London) and later by the British government and, together with the slightly earlier term "Near East," soon passed into general use. Both names are recent but not modem; both are relics of a world with Western Europe in the center and other regions grouped around it. Yet in spite of their obsolete origin and parochial outlook, both terms, "Middle East" in particular, have won universal acceptance and are now used to designate this region even by Russians, Africans, and Indians, for whom in fact it lies south, north, or west-even, strangest of all, by the peoples of the Middle East themselves. So useful has the term been found to be that the area of its application, as well as of its use, has been vastly extended, from the original coastlands of the Persian Gulf to a broad region stretching from the Black Sea to equatorial Africa and from the northwest frontier of India to the Atlantic.'

It is indeed remarkable that a region of such ancient civilization-among the most ancient in the world-should have come to be known, even to itself, by names that are so new and so colorless. Yet if we try to find an adequate substitute for these names, we shall have great difficulty. In India the attempt has indeed been made to displace the Western-centered term "Middle East" by another, and the area has been renamed "Western Asia." This new geographical expression has rather more shape and color than "Middle East," but is not really very much better. It is no less misleading to view the region as the West of an entity called Asia than as the Middle East of another unspecified entity; moreover, it is misleading to designate it by a name that, even formally, excludes Egypt.

The reason for the rapid spread and acceptance of the terms "Near East" and "Middle East" must be sought in the fact that for Europeans this region was, for millennia, the East-the classical, archetypal, and immemorial Orient which had been the neighbor and rival of Greco-Roman and Christian Europe from the days when the armies of the Great King of Persia first invaded the lands of the Greeks until the days when the last rearguards of the Ottoman sultans withdrew. Well into the nineteenth century, the countries of Southwest Asia and Northeastern Africa were, for the European, still simply The East, without any need for closer specification, and the problem of their disposal was the Eastern Question. It was only when Europe became involved in the problems of a vaster and more remote Orient that a closer definition became necessary. When the Far East began to concern the chanceries of Europe, some separate designation of the nearer east was needed. The term "Near East" was originally applied in the late nineteenth century to that part of southeastern Europe that was then still under Turkish rule. It was "Near" because it was, after all, Christian and European; it was "East" because it was still under the rule of the Ottoman Empireof an Islamic and "Eastern" state. For a while, the Near East was, so to speak, extended eastward and, especially in American usage, came to embrace the greater part of the territories of the Ottoman Empire, in Asia and Africa as well as in Europe. In British usageperhaps because on closer acquaintance the Near East proved less near than had at first been thought-the term "Near East" has almost disappeared and has been replaced by a vastly extended Middle East covering large areas of Southwest Asia and North Africa. There is still considerable variation in the usage of the latter term.

In spite of its recent emergence and a continuing uncertainty as to its precise location, the term "Middle East" does nevertheless designate an area with an unmistakable character and identity, a distinctive-and familiar-personality shaped by strong geographical features and by a long and famous history.

The most striking geographical characteristic of the Middle East is certainly its aridity-the vast expanses of wasteland in almost every part of it. Rainfall is sparse, forests are few, and, except for a few privileged areas, agriculture depends on perennial irrigation and requires constant defense against natural and human erosion. Most of the Arabian peninsula, apart from its southwestern and southeastern corners, consists of desert; the Fertile Crescent is little more than a rim of irrigable and cultivable land around its northern edges. Egypt, too, is nearly all desert, save only for the green gash of the Nile, opening out into the delta toward the shore of the Mediterranean Sea. Much of North Africa is now infertile, except for the coastal belt and a few oases. In Turkey and Iran, much of the central plateau consists of desert and steppe, while beyond them, to the north, lie the vast steppelands of Eurasia.

Some of the deserts, as in the Empty Quarter of Arabia and the Western Desert of Egypt, are utterly barren; others support a thin but historically important population of nomadic herdsmen who provide animals for meat, milk, and transport and participate, in various ways, in the exploitation of the transdesert trade routes. In modern times, the herdsmen are losing an important part of their economic raison d'etre as horse and camel are replaced by car and truck-mounts that they are unable to breed. They can, however, feed them, and in some areas they and their neighbors are supplied with vast quantities of the fodder that these mounts consume. The exploitation of this resource-petroleum-is bringing social as well as economic changes of incalculable scope and extent.

The impact of the discovery and exploitation of oil in the Middle East was dramatic, in that this was a region previously deficient in sources of fuel and energy. There was no coal, and even in the Middle Ages, there was very little wood, so that leather and wool-products of the nomads-were used for both furnishings and clothes. The presence of oil was known, but its potential was not realized. In preIslamic Iran, it was used to maintain the sacred flame in Zoroastrian temples; in Islamic times, it was an ingredient in the manufacture of explosive mixtures for use as weapons of war. Apart from water and windmills-and these few in number as compared with even early medieval Europe-there was no energy source beyond animal and human strength. This may also help explain the lack of technological progress after the remarkable achievements in this respect of Middle Eastern antiquity.

Between the herdsmen and the tillers of the soil there is an ancient feud. One of the earliest records of the conflict between them is contained in some verses of the fourth chapter of the book of Genesis, which tells of the quarrel of Abel, the stockraiser, and Cain, the farmer. In the Bible it is Cain who kills Abel; more frequently in the history of the Middle East it has been the herdsmen who killed the peasants or established their rule over them. The policing of the desert borders and the security of the desert trade routes were always problems for the governments, whether local or imperial, that controlled the settled country. They usually found it more convenient to deal with the desert by indirect means, through some sort of nomadic or oasis principality to which they gave support and recognition in return for commercial facilities and political and military help when required. To take one example among many: Byzantium and Persia, the two world powers that confronted each other across the Middle East in the sixth and early seventh centuries, both maintained their Arabian buffer states, whose rulers they encouraged with gifts of gold and of weapons, high-sounding titles, and visits to the imperial capital. This method was cheaper, easier, and more effective than trying to rule the desert directly. Its merits are in no way diminished by the fact that in the seventh century the Arabs came out of the desert and overwhelmed both of them.