The Silent Boy (14 page)

Authors: Lois Lowry

"You pin it to the wall," I explained, "and then each child has a blindfold on, one after another, and they are spun around in a circle, and then they go to the donkey all blinded, holding a tail, and try to pin it in the right place."

Peggy looked dubiously at the faded donkey I had laid out on the dining room table.

"See how there are pinholes in wrong places? Look! There's a hole in his ear! Jessie Wood did that at my seventh birthday. Then she cried because she didn't win the prize."

"What prize?"

It was surprising to me that Peg knew so little about birthday parties. "The one who gets closest to the tail place gets a prize. At my last party, the one before the chicken pox, the prizes were handkerchiefs for the boys and thimbles for the girls.

"And we do a spider web! Mother will wind string all around, one for each child, and it's like a spider web. You follow your string and at the end you find a surprise! Usually it's just a sweet."

"My land. What else?"

"Oh, games, of course. London Bridge, and Farmer in the Dell. We can do those out in the

backyard. And Naomi will make a cake, and there will be ice cream."

Peggy folded the donkey oilcloth carefully and put it in the bottom drawer of the buffet, where the tablecloths were. "It's time to fetch Mary down from her nap," she said.

"Peggy?"

"What?"

"I want to invite Jacob to my birthday party."

She looked at me, astonished. "

Jacob?

"

At that moment my kittenâfull-grown now, a good-sized, good-natured catâhopped down from the chair where he'd been sleeping. He strolled through the room and rubbed himself against my shoe. "He gave Goldy to me," I reminded Peggy.

"Jacob don't go to parties," Peggy said. "He never."

I picked up Goldy, and he hung dangling in my arms like a doll with floppy arms and legs. I listened to his purr. I knew Peggy was right, that it wouldn't do, that Jacob wouldn't understand a party, that the other children would be uneasy if he came.

Â

I told him, though, that I had wanted him to come.

"I'm going to have a birthday party next week, Jacob," I said, when I saw him next. "I wanted to

invite you, but Mother said it had to be just children from my class at school.

"I'll be nine," I added.

I wasn't sure that he was even listening, or, if he was listening, whether he understood. He was holding Goldy on his lap, and he stroked the cat's neck with one finger and imitated the purr. We sat side by side on stacked hay in the stable.

"Anyway, I wanted to give you these." I reached into my pocket and pulled out the two big cat's-eye marbles I had brought him. They were both deep brown, flecked with gold and black. I had chosen them from the bag of marbles that Mother had bought at Whittaker's Dry Goods for party prizes and favors. Jacob took them from me and they clicked together in his hand.

He imitated the click with his tongue against his teeth, and smiled in that odd way he had, with his eyes looking someplace else. The horses shifted in their stalls. Goldy yawned and stretched. Outside, a wind came up, and I could hear dead leaves whisper as they broke loose and fell from the branches of the big ash tree in the yard. Our back door opened, and from the kitchen Peggy called me to come in. Jacob looked up at the sound of her voice, and his knees jiggled, but he stayed silent.

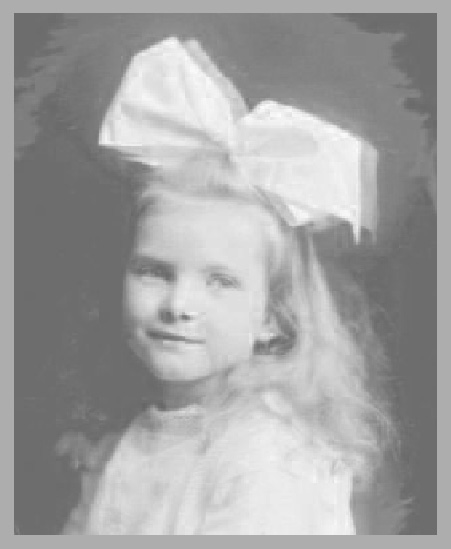

I had a new white lawn dress and a huge hair ribbon, and Naomi had made me a cake with buttercream frosting. It was warm enough that Saturday afternoon that Father moved the kitchen table to the backyard and we took the chairs outdoors, too, and set them around the table. Then Mother tied a pink bow on the back of my chair, for my birthday. She laid the table with a yellow cloth and we used my favorite plates, white ones with pink flowers.

I helped to wrap the prizes and watched while Father nailed the oilcloth donkey to the side of the

stable. The sun was shining and there were still some chrysanthemums in bloom. Only one thing was wrong. Peggy wasn't there.

Peggy had lived with us now for more than a year, and it felt as if she was part of the family. Mother joked that when Mary began to talk, she would probably call Peggy "Mama."

But today, on my birthday, it was Mother and Naomi who tended Mary, as they had for the past two days. Peggy had been called home for an emergency. Our telephone had rung late two nights before, when I was already in bed, and I heard Father go up to the third floor to get Peggy. Then, after a quick flurry of gathering her things, Father hitched up the horses and took her home.

"She'll be back soon," Mother had reassured me in the morning as I ate my breakfast. The house seemed subdued without Peggy there; she usually bustled about, entertaining Mary, helping me get my things for school, talking to Mother about the plans for the day.

"Will she be here for my party?"

Mother frowned. "I don't think so, Katy. I expect she'll be gone about a week. There's illness in her family, and you know it always takes awhile to heal."

I remembered my own chicken pox and agreed. It takes

forever.

"Who is ill?"

"I don't know," my mother said.

I guessed that it was Peg's mother who was ill, and I worried for their family because the little girl, Anna, needed a mother. Even with Nellie there, and Peggy, Anna would be frightened if her mother was ill.

I didn't believe it could be Mr. Stoltz, that big strong man who seemed as if nothing could fell him. And I knew it wasn't Jacob. I had seen Jacob just the night before, in our usual place.

He had shown me, pulling them from his pocket, that he carried the two marbles with him. It was odd how Jacob never looked at meâhis eyes were always to the side, or his face turned away, and he couldn't, or didn't, ever speakâbut he communicated in his own ways. Looking sideways toward the horses, he held out his hand and showed me the marbles; he made the small clicking sound again and nodded his head a little.

"Tomorrow is my birthday party," I told him, "and the boys who comeâAustin and Norman and Kennethâwill get marbles. But yours are the best. I chose them out of all the ones we had."

Click. Click. Click.

"The girlsâJessie and Anne are the ones who are comingâwill get hair ribbons as favors. I'll get all sorts of gifts, because I'll be the birthday girl," I told him with satisfaction.

Click. Click.

"Peggy's at home, isn't she? And Nellie. I hope things get better there soon. Is it your mother who is ill?"

He returned the marbles to the pocket of his overalls. He was silent now but began to sway slightly, back and forth. His fingers tapped rhythmically on his own knee.

"My baby sister, Mary, was sick last week, with a cough and a fever. But Father gave her medicine and she's all better now. Father says that sometimes

time

is the best healer. But medicine helps, too."

He continued to rock back and forth, seated there on the hay bale.

"And love, of course. My mother says that, and Father says he agrees. When Mary was sick, Mother stayed with her every minute, rocking her, and nursing her, and wiping her forehead with a cool cloth.

"The window right above the kitchen is Mary's window," I said, even as I knew that he would not be interested, "and my room is down the hall, over the porch. My room has blue curtains. You can see them from the yard."

I was just talking aimlessly because I did not know how I could help him. It was clear that Jacob was distressed about something, but it was not something I could understand or make right.

He made a sound and I thought he might be

crying, but I couldn't see his face. Finally, not knowing what to do, I stood up.

"Ihavetogoinnow.Ihavetogotobedearly because of the party tomorrow. Mother wants to wash my hair in the morning, and it takes forever to dry."

I tried to think of something less foolish, more helpful, to say.

"I hope things are better in your family soon, Jacob."

Oddly, I wanted to lean forward and kiss the top of his head. It was what both of my parents did when I needed comforting, and it seemed right, somehow, to try to comfort Jacob. But as always he was shielded from the world by the thick cap, and I knew he would recoil from such a touch.

He was a large boy, fourteen by then, with big hands resting on his own knees, and his feetâso often bare, but now, in October, in thick country shoesâalmost the size of Father's. I had seen him doing farm chores and knew that he was strong and had a way with animals. Yet he seemed in other ways to be as young and unformed as Mary, with no language but sounds and needs that one could only guess.

Â

Now, in the sunny Indian summer afternoon, the yard was decorated with ribbons and the yellow tablecloth heaped with brightly wrapped gifts. We children played musical chairs, with Father winding the Victrola again and again and Mother removing a chair from the line each time, so that one child would be left out until at the end there would be a winner. The poor old donkey on the stable wall was jabbed again and again, in his nose and tummy and ears, until finally Austin Bishop won the prize by coming close, at least, to where a tail should be.

We went indoors to untangle the spider web that Mother had created with different-colored ribbons and found ourselves crawling under furniture and behind the coat tree to come upon our sweets at the end of each. My cat followed us, leaping again and again to paw at the dangling ribbons, until finally we had to banish poor Goldy to the cellar. Then everyone gathered in the yard to watch me open my presents: embroidered hankies from Jessie, paper dolls, a new skipping rope, a pincushion, and a set of pick-up sticks. Gram had sent a book,

Anne of Green Gables,

from Cincinnati. Finally, Naomi served the cake and ice cream on the table under the ash tree.

The air turned cool after the party guests had gone home. A sudden chilly wind came up, and we hurried to bring in the table and the gifts because it looked like rain was on the way. With so much excitement in the yard that afternoon, and the

cake and ice cream, and then the cleaning up to help with after the party guests had gone, I had completely forgotten the strange, sad visit with Peggy's brother the evening before. It was only after my party dress, smeared with cake frosting, was bundled up with the other laundry and I was in my nightgown, sound asleep on a cold rainy night with my new book on the table beside my bed, that Jacob Stoltz reentered my life in a new and terrible way.

Â

The ringing of the telephone woke me in the middle of the night. Or perhaps I was already awake. My memories of that night became confused, afterward, but I believe that something, perhaps the onset of the heavy rainstorm, had woken me earlier. I had heard unfamiliar sounds in the house, which had made me sit up in bed. I listened in the dark, thought I heard a door open and close quietly, thought I heard footsteps on the stairs. There was only silence after that, except for the sound of rain. I decided it had been a dream and drifted off to sleep again. Then, later, the telephone rang.

At our house, we did not have to listen for the rings to make our own combination, the way most others did. Father being a doctor, we had our own line, and the ring was always for us. It was not

unusual for the telephone to ring late at night. People seemed to get sickest then, and often Father would have to dress hastily and leave the house, carrying his medical bag, when it was dark and quiet throughout the town.

So I was not surprised by the ringing of the telephone, or hearing Father's feet on the stairs as he went down to answer it, or his murmured voice to Mother as he dressed in the night. I snuggled back again into my pillow, imagining him hurrying to the hospital, probably, only two streets away. Maybe he would not even take the buggy. He would walk quickly, carrying his bag. In the morning, at breakfast, he would tell us of a sudden illness and a family stricken with fear. Once it had been a small child: meningitis, Father had said, but she would get well. Once an old man we knew slightly from church: his heart, it was, and he would not recover. We watched the funeral procession go from the church to the cemetery a few days later.

But on the night of my birthday, it was different. As I lay there half-awake, I became aware of other, more unusual sounds. I heard my father go to the telephone again, and when he spoke to the operator I recognized the number that he gave her: 426. He was calling the Bishops house, next door. Through my slightly opened bedroom window, even through the rain, I could actually hear their

telephone ring; and after a moment I saw lights go on in their parlor, and I knew Mr. Bishop had risen, as my father had, to answer it.

I heard my father speak, though I could not make out the words. Then he left the house and I saw him move through the rain across the yard toward the Bishops . I saw the two men meet on the porch and talk. While I watched they went to the barn, where Mr. Bishop kept the Ford motorcar, and then I heardâI'm sure the whole neighborhood heardâthe sound as he cranked the motor to a start and in a moment, the loud sputter and rattle as it moved from the barn to the alley, then the street, and off. I had thought Father was in the car with Mr. Bishop, but after a moment I could I hear sounds in our stable and I knew Father was hitching Jed and Dahlia. Then he, too, was gone, in the buggy.