The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (22 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

However, there is little evidence to support the idea that a curse was ever laid on this tomb. Although many folktales describe elaborate curses promising a swift and terrible death to anyone who disturbs a mummy’s grave, archaeologists have actually verified the existence of protective curses at only two Egyptian tombs, and both of these simply threaten graverobbers with harsh judgment by the gods. The curse inscribed on King Tut’s tomb—if there ever was one—has mysteriously vanished. Howard Carter himself lived for another seventeen years after disturbing Tut’s rest, eventually becoming one of the world’s most famous and admired Egyptologists.

In sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England, public cursing was commonplace. It was not unusual, for example, to see someone in the town square fall to his knees and call upon God to burn his enemies’ houses, blight their crops, kill their children, destroy their possessions, and bring down on their heads “all the plagues of Egypt.” While such rants might seem harmless, cursers were well advised to exercise some caution. If the intended victim did become ill and the curser developed a reputation for success, he or she could well end up in jail, accused of witchcraft.

ander off the familiar sidewalks of Diagon Alley into a dingy side street near Gringotts Bank and you’ll find yourself in Knockturn Alley, home to purveyors of shrunken heads,

ander off the familiar sidewalks of Diagon Alley into a dingy side street near Gringotts Bank and you’ll find yourself in Knockturn Alley, home to purveyors of shrunken heads,

hands of glory

, hangman’s rope, poisonous candles, and other such sinister goods. Although Hagrid ventures here in search of flesh-eating-slug repellent, most visitors to this part of town are practitioners of the Dark Arts—the branch of magic devoted to causing harm to others.

Like every other kind of magic, the Dark Arts (also known as black magic) have been around for thousands of years. While some members of early civilizations developed

spells

and

magic words

to try to cure disease, bring rain to parched fields, or protect a village from enemy invasion, others were working on

curses

and other supernatural means of inflicting pain and misfortune on their neighbors. Such methods might be used to exact revenge for a personal insult, to eliminate a business competitor, or to get the better of a political opponent. When the Roman general Germanicus died in

A.D

. 19, evidence that someone had used black magic against him was found in the form of human bones, written curses, and pieces of lead (then known as the metal of death) hidden under the floor and behind the walls of his bedchamber.

At Hogwarts, young students learn about the Dark Arts by studying the wicked ways of

red caps, kappas, werewolves

, and other menacing creatures. More mature pupils are taught to defend themselves against the curses of evil

wizards

and

witches

who use these illegal means to gain total control over others, to inflict torture without ever laying a finger on the victim, or even to kill. Some dark practices are considered too evil to teach to students—most notably the method for creating a

horcrux

, which requires an act of murder.

Another form of black magic that doesn’t seem to be taught at Hogwarts is

image magic

, one of the oldest and most widely practiced dark arts. This involves creating a drawing or clay or wax model of the victim and then intentionally harming or destroying it. Any damage inflicted on the model—also known as an effigy—is supposed to hurt the victim as well. In ancient India, Persia, Africa, Egypt, and Europe, doll-like wax effigies were common, since they were easy to create and could be destroyed by melting, a method alleged to cause the victim to die of a wasting illness. Small dolls might also be made of clay, wood, or cloth and painted to look like the victim. Other common methods of harming an effigy included sticking it with pins or knives (believed to cause a person pain or sickness) or, if it was made of animal or vegetable matter, burying it in the ground so it would decompose.

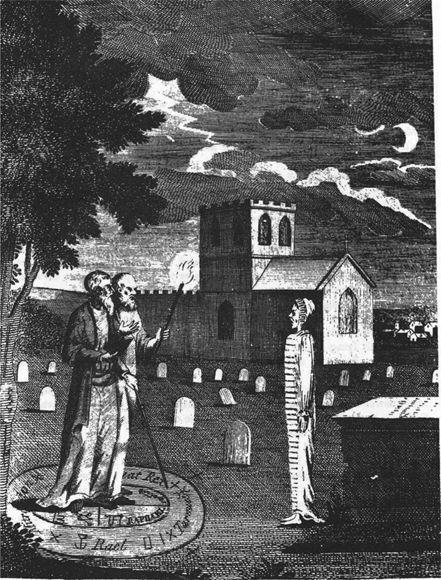

Still another ancient form of black magic was

necromancy

(from the Greek

nekros

, meaning “corpse,” and

mancy

, meaning “prophecy”)—attempting to raise the spirits of the dead for purposes of

divination

. No longer bound by the earthly plane, the dead were believed to have access to information about both the present and the future that was unavailable to the living. Necromancy appears in the Bible, was practiced in ancient Persia, Greece, and Rome, and experienced renewed popularity in Renaissance Europe. While some necromancers tried to raise actual corpses (and a few were accused of trying to send those corpses to attack the living), most were content to summon only the spirit of the dead person by performing rituals over the grave, uttering incantations, and drawing magic words and symbols on the ground. Often the necromancer would surround himself with skulls and other images of death, wear some clothing stolen from a corpse, and concentrate all his thoughts on death as he waited for the spirit to appear. Once it did (any small sign, such as the flickering of a candle, might be taken to indicate the spirit’s presence), he would ask it questions—sometimes about life’s great mysteries, sometimes about the future, and sometimes about more mundane concerns, like where to find buried treasure. Although the purpose of necromancy was not always to harm people, the process of calling upon (and perhaps disturbing) dead souls has generally been considered immoral and despicable, earning its place among the Dark Arts.

Protected by a magic circle, sixteenth-century necromancer Edward Kelly and his assistant, Paul Waring, conjure a spirit in a churchyard in Lancashire, England

. (

photo credit 17.1

)

Some writers have suggested that all magic is really “colorless”: Whether a practice is “black magic” or “white magic” depends upon its intention. For example, melting a wax effigy in order to kill a cruel dictator might be considered white magic by the people being oppressed by the dictator, but black magic by the dictator himself. Others have suggested that the war between black magic and white magic is an ongoing expression of man’s dual nature—our capacity to do good, but also to harm. Wizards, like the rest of us, can use their powers to create, help others, and contribute to the world. Or, like the Death Eaters, they can give rein to a different aspect of human nature—to be selfish, domineering, power-hungry, and capable of terrible atrocities. As Dumbledore tells Harry, which side you’re on is not a matter of destiny but a matter of choice.

emons—malicious spirits of world folklore, mythology, and religion—come in all shapes and sizes and are almost always up to no good. The vicious English

emons—malicious spirits of world folklore, mythology, and religion—come in all shapes and sizes and are almost always up to no good. The vicious English

grindylow

that attacks Harry in the Hogwarts lake is a demon. So is the Arabian

ghoul

in the Weasleys’ attic and the Japanese

kappa

studied in Defense Against the Dark Arts. Terrifying tales of demons and their wicked ways can be found in most cultures. Although they are now recognized as creatures of the imagination, demons were once considered quite real and were held responsible for much of the evil and suffering in the world.