The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (18 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

nlike the brooding and philosophical centaurs that roam the

nlike the brooding and philosophical centaurs that roam the

Forbidden Forest

, the original centaurs of Greek mythology were a rowdy lot. Living in herds in the mountains of northern Greece, they pursued a wild and lawless lifestyle. Half man and half horse, the centaurs were beautiful to behold, but they were always ready to drink, fight, and seduce human women. Once invited to attend the wedding of their neighbor, King Pirithous of Laipithae, the drunken centaurs assaulted the female guests, tried to abduct the bride, and started a bloody battle with their host and his supporters—a contest they lost, to the great relief of all who lived nearby.

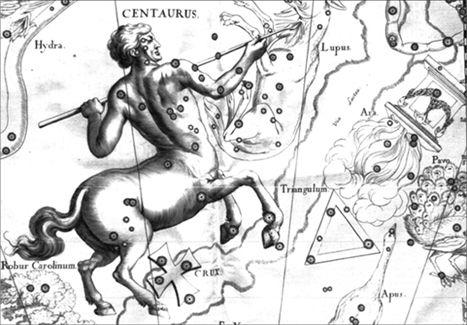

The constellation Centaurus is visible only to people living near or south of the equator. It contains the third brightest star in the night sky, Alpha Centauri, which is also the closest star to our own sun

. (

photo credit 11.1

)

As in any large family, there were a few centaurs that rebelled against the wild ways of their kin, preferring a life of virtue and scholarly contemplation. The most famous was Chiron. Renowned for his wisdom and sense of justice, Chiron was skilled in medicine, hunting,

herbology

, and celestial navigation. He was also a master of

astrology

and

divination

, talents clearly inherited by the sky-gazing centaurs of the

Forbidden Forest

. Most of all, Chiron was famed as a teacher to many young men destined for greatness, including Heracles (better known by his Roman name, Hercules), Achilles (the hero of the Trojan War), Jason (captain of the Argonauts), and Asclepius, god of medicine. It’s likely that Albus Dumbledore had Chiron’s mentoring skills in mind when he appointed Firenze to instruct the future heroes of Hogwarts.

The myths tell us that Chiron might have gone on teaching young heroes indefinitely, for he was born immortal, the offspring of the Titan Cronos and the nymph Philyra. But he chose to give up his immortality after he was accidentally wounded by a poisoned arrow belonging to his friend Heracles. When the pain became unbearable, he asked Zeus to allow him to die. Zeus granted Chiron’s request but immortalized him nonetheless by placing him in the sky as the constellation

Centaurus

.

Centaur lore provided a popular subject for Greek and Roman artists. Centaurs were typically shown fighting humans or bashing each other with tree limbs. The favorite scene, however, was the wedding brawl between the centaurs and the Lapiths, which was painted on pottery and can be seen in sculptural form on the side of the Parthenon in Athens, Greece. More serene scenes, such as Chiron working at a potter’s wheel or receiving a hero for training, were also popular. During the Middle Ages, images of the centaur were used in Christian symbolism to represent the twofold nature of Christ, at once human and divine. As a more general symbol, the centaur represents the dual nature of man—part creature of reason, part beast.

hen we use the word “charm” in everyday conversation, we’re usually referring to a certain sense of social grace, a rare enchanting quality that makes some people more alluring and persuasive than others. But the term “charm,” which derives from an old Latin word for “song” or “ritual utterance”

hen we use the word “charm” in everyday conversation, we’re usually referring to a certain sense of social grace, a rare enchanting quality that makes some people more alluring and persuasive than others. But the term “charm,” which derives from an old Latin word for “song” or “ritual utterance”

(carmen)

, has many different meanings, most of which are totally unrelated to a person’s appearance or social skills. In the world of witchcraft and sorcery, a charm is usually a phrase that is recited or written down to achieve a particular magical effect. Thus, Harry utters a special summoning charm

(Accio Firebolt!)

when he wants to call his

broomstick

to his side, while Hermione uses a levitation charm

(Wingardium Leviosa!

) to make a feather float.

As the students in Professor Flitwick’s charms class quickly learn, there are charms for almost every occasion. If you know the right words, you can charm your way into riches and fame, conquer your enemies, or capture men’s hearts. One Old English charm even confers protection from malevolent

dwarfs

. But charms are most commonly associated with medieval wise women, who used them for fairly humble tasks, such as healing the sick, protecting crops and livestock from disease, and defending the local villagers from

curses

.

Although a few charms involve combining words with actions (such as spitting or waving a

magic wand

), most require no special ritual or magical tools to be effective. Charms are even said to work in purely written form. Some of the earliest known charms were simply scraps of parchment or paper, inscribed with a

magic word

like

abracadabra

, and then worn as protective

amulets

around the neck.

Simple spoken charms became especially popular in Europe around the twelfth century, when the Catholic Church began to place great emphasis on the power of spoken prayers and papal blessings. Throughout the Middle Ages, it was common for

witches, wizards

, and even local Church officials to adapt Christian prayers for magical purposes. The Lord’s Prayer was routinely rewritten and used as a charm against disease, pestilence, and personal misfortune. One thirteenth-century French memoir actually describes how a parish priest used this prayer “to deliver Arnald of Villanova from the warts on his hands!” Other charms mixed magic words with the names of saints and were used to treat maladies such as snakebites and burns.

The notion that a charm can affect us in a magical or enchanting way has given rise to many “charming” phrases and expressions. A smooth operator can “charm the pants off” someone or “charm a bird from a tree.” Quaint towns have “Old World charm,” and music, according to the English playwright William Congreve, “has charms to soothe a savage breast.” Prince Charming usually gets what he wants, and those who often escape from danger are said to lead a “charmed life.” “How charming” is usually a sarcastic remark, but “the third time’s a charm” shows that persistence pays off. And any particularly effective technique for getting what you want—a word, a smile, or a bill slipped into the hands of a maître d’—is said to “work like a charm.”