The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (37 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

The Hand of Glory is not confined to the realm of folklore. Detailed instructions for making the Hand exist in real spell books. A French book of magic called

The Marvelous Secrets of the Natural and Cabalistic Magic of Little Albert

, published in 1722, says that the Hand must be cut from a corpse and wrapped in a piece of sheet, squeezed until all the blood has drained from it, and pickled for fifteen days in an earthenware jar with pounded salt, peppercorns, and saltpeter (potassium nitrite). It should then be dried completely in the sun during the dog days of summer—the hottest days of the year, associated since ancient times with the influence of the dog star, Sirius. If the sun’s rays are insufficient, the Hand should be placed in a furnace fed by ferns and vervain, an herb used in many magic rituals. The fat that runs from the hand is to be collected and mixed with wax to make a candle, which is stuck between the fingers to complete the magical object.

The same book helpfully offers a method to defend yourself against an intruder with a Hand of Glory. Make an ointment from the blood of a screech owl, the fat of a white hen, and the bile of a black cat, and smear it across your doorways, chimney stack, window frames, and anyplace else someone might enter your home.

Several accounts exist of real people attempting to use a Hand of Glory, the most famous being at a house in Loughcrew, Ireland, where in 1831 burglars broke into a house armed with Hand of Glory, confident that it would render the residents unable to defend themselves. But the Hand failed them; the owner awoke and sounded the alarm. The burglars fled, leaving the Hand behind. Although the whereabouts of this Hand of Glory are now unknown, you can see one for yourself at the Whitby Museum in Yorkshire, England.

aving a green thumb can be mighty handy for a

aving a green thumb can be mighty handy for a

wizard

. Many of the ingredients for magical

potions

can be found in the well-stocked garden, as can remedies for all kinds of maladies both natural and supernatural—from acne to snakebite to

petrification

. Certain herbs may even protect you from the magical machinations of your enemies. The secret lies in knowing which plants do what, and how best to grow and harvest them. That’s what herbology is all about.

Herbs have been used in both magic and medicine for thousands of years. The systematic study of herbs dates back to the ancient Sumerians, who described medicinal uses for caraway, thyme, laurel, and many other plants that could be growing in your backyard today. The first known Chinese herb book (or “herbal”), written in about 2800

B.C.

, describes medicinal uses for 366 plants. The ancient Greeks and Romans used plants for medicine, seasoning, cosmetics, scents, and dyes. The more superstitious among them also used herbs as

amulets

that were worn in small cloth bags tied round the neck to ward off evil spirits, disease, or the

curses

of an angry neighbor. In Homer’s

Odyssey

, the hero is given an herb called

moly

to protect him from the

spells

of the sorceress

Circe

. Elsewhere in mythology, magic herbs are associated with

witches

such as Hecate and Medea, who used them to create

potions

that bestowed great gifts on those they favored and terrible agony on those they wanted to destroy.

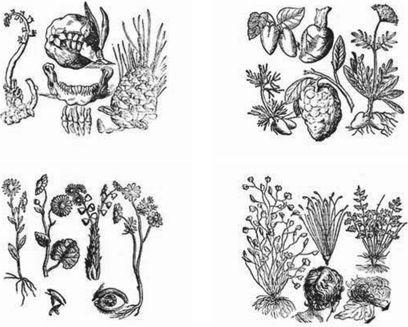

A sixteenth-century illustration of one of the basic rules of herbology: A plant’s appearance shows how it can be used. Plants that look like teeth cure toothache; those shaped like hearts are good for heart ailments; those that resemble eyes sharpen the eyesight; and hairy plants offer a cure for baldness

.

During the Middle Ages, most everyone knew of a local “wise man” or “wise woman” who used herbs to treat injuries and ailments and provide solutions to all sorts of personal difficulties, from a dry well to an overbearing mother-in-law. These prescriptions drew on folk beliefs about the medicinal and magical properties of plants that had been passed down for generations. Many cures were based on the principle that every plant had been stamped by God with a visible image of its role in medicine, so by simply looking at a plant you could tell what it was good for. The color of the flowers or fruit, the shape of a root or leaf, the texture of a petal or stem—all might hold clues to a plant’s medicinal properties. For example, yellow-flowered plants such as goldenrod were said to cure the yellow complexion caused by jaundice, plants with red leaves or roots were used to treat blood disorders or wounds, and the purple petals of the iris were made into poultices for bruises. If a plant resembled a human organ, it was thought to be beneficial in treating that organ. Lungwort, so named because of the lunglike spots on its leaves, was used to treat pulmonary complaints, while the three-lobed leaf of hepatica (or liverwort), said to resemble the human liver, was used for liver disorders. Quaking aspen leaves were used to treat the shaking symptoms of palsy, and flowers that resembled butterflies were recommended for insect bites.

Many ailments were believed to be caused by supernatural forces, but there were herbal treatments for those as well. The local wise woman or herbalist might advise you to hang a blackberry wreath to ward off evil spirits, to stuff your keyhole with fennel seeds to keep out the

ghosts

, and to spread the juice of the foxglove plant on your floor to protect yourself from

fairies

. Herbs were also expected to work their magic on a variety of more down-to-earth problems. A traveler who feared falling asleep at the wagon reins, for example, would be instructed to carry mugwort, which was reputed to drive off sleep by its mere presence. A treasure seeker might be given chicory, said to be capable of opening locked doors and chests. A woman eager to bear children might be advised to plant parsley around her home, and a young man who hoped to win the girl of his dreams might be told to pick some yarrow while reciting a love

charm

.

Knowing which plants were useful for what purpose was only half the battle. It was also crucial to know the proper time and manner for gathering each plant. Many herbalists believed that the properties of plants, like the characteristics of people, were directly influenced by the movements of the stars and planets. One enthusiast of astrological botany insisted that “if a plant be not gathered by the rules of astrology, it hath little or no virtue in it.” Thus plants believed to be associated with Saturn, such as hemlock and belladonna, were to be gathered when Saturn was in the appropriate position in the sky, and so forth. A more basic rule of thumb was that it was best to gather herbs at night, preferably when the moon was full and the plants were thus at their most potent. No doubt that’s why Hermione had to follow careful instructions when gathering fluxweed for Polyjuice Potion.

But many plants had rules all their own. If you expected the simple blue chicory to open any locks, for example, you had to cut it using a gold blade at noon or midnight on St. James Day, July 25. If you spoke a single word during this process you would supposedly die on the spot. And if you hoped to use peonies to protect your livestock and crops from stormy weather, you had better be sure there were no woodpeckers around when you did your harvesting. Legend held that if one of these birds caught you in the act you’d go blind. With all these rules, and so many mortal dangers, it’s no wonder Hogwarts students are required to spend so many years studying herbology.

hen Hermione’s teeth suddenly grow past her chin, she knows she’s been hexed by the spiteful Draco Malfoy. A hex is an evil

hen Hermione’s teeth suddenly grow past her chin, she knows she’s been hexed by the spiteful Draco Malfoy. A hex is an evil

spell

or

curse

placed upon a person or object and intended to cause harm. Among those who don’t have Madam Pomfrey around to reverse the ill effects, being hexed is considered very dangerous indeed.