The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (34 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

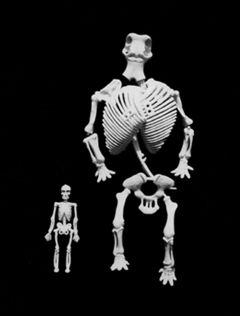

That the bones of a prehistoric quadruped such as a mastodon might be identified as those of an enormous two-legged humanoid is not as implausible as it might seem. Except for size, a human thigh bone and a mastodon femur look alike (the mastodon femur is three times longer, which would have made the imagined giant three times taller than the average Roman, or fifteen feet tall). The vertebrae and shoulder blades also bear similarities. And although the skull could have been a giveaway, it was often missing, having disintegrated faster than the other bones. Even when skulls or other clearly nonhuman bones were found, they were easily attributed to one of the many legendary monsters who possessed multiple heads and hundreds of arms, feet, or tails. Moreover, many large bones were unearthed in the specific areas where legends told that giants once had lived—confirming the beliefs of the ancients who dug them up, but suggesting to modern scholars that those very legends may have been shaped by the discovery of similar bones generations earlier.

On the basis of the numerous enormous fossils pulled from the earth, many ancient authorities drew the same conclusion. “Its is obvious,” wrote Pliny the Elder, “that the whole human race is becoming shorter by the day.”

The skeleton of a mammoth was usually found scattered and incomplete. Here, a modern-day scholar demonstrates how they could be arranged to form a convincing “giant.”

(

photo credit 30.2

)

hese days, if you’re looking for a gnome, you may need to go no further than the neighbor’s front lawn. In Europe and in the United States, “garden gnomes”—cheerful plaster statues of bearded little men with pointed red hats—are popular outdoor ornaments. If your neighbors happen to be

hese days, if you’re looking for a gnome, you may need to go no further than the neighbor’s front lawn. In Europe and in the United States, “garden gnomes”—cheerful plaster statues of bearded little men with pointed red hats—are popular outdoor ornaments. If your neighbors happen to be

wizards

, however, their gnomes will be far more animated than the plaster versions. As visitors to the Weasleys’ vegetable patch know, gnomes can be giggly little pests who must be driven off like any other backyard intruders.

No one knows exactly how gnomes came to be associated with gardens. Some suggest that, as statuary, they first appeared as welcoming figures at the entryways to grand buildings and then were adopted for more personal use. Another possibility is that the link emerged from folklore, where gnomes were traditionally associated with the earth.

In German lore, gnomes, like

dwarfs

, live underground, where they mine for precious metals and guard treasure. Remarkably, they can move through the earth in any direction without the benefit of a tunnel, just as a fish moves through water. Industrious and good-natured, they are usually depicted as being old and hunchbacked or otherwise misshapen. Their skin is always earth-toned (gray or brown), so they blend easily with their surroundings. If threatened, a gnome can literally dissolve into the ground or into a tree trunk.

Although there are plenty of tales of gnomes who enjoy the outside world, some authorities claim that gnomes turn to stone if exposed to the light of day. If that’s the case, perhaps some of those decorative garden gnomes are simply the victims of too much sun.

pen up the dictionary and you’ll find “goblin” defined as a “mischievous and ugly

pen up the dictionary and you’ll find “goblin” defined as a “mischievous and ugly

demon.”

Take one look at the clever and efficient goblins who run Gringotts Bank, however, and you’ll know these magical beings have not always been cast in such an unflattering light. In medieval English folklore, goblins are usually portrayed as helpful, if temperamental, imps or household spirits. Like Scottish brownies, French

gobelins

, and German

kobolds

, they frequently attach themselves to a specific person or family and move into their home. They are particularly fond of isolated farmhouses and cottages in the countryside.

Although goblins vary greatly in size, most are thought to be about half the size of an adult human. They have gray hair and beards, and their bodies or facial features tend to be grotesquely distorted in some way. Griphook, the goblin who helps Harry break into Gringotts, has an oversize head. Goblins may have extra fingers or toes, missing ears, upside-down eyelids, or jointless limbs. Some also have unusual speech defects, strange lisps or high-pitched, squeaky voices.

If they are well fed and well treated, most household goblins devote themselves to keeping things neat and orderly. They have a soft spot for children and will bring gifts to well-behaved youngsters. But beware the angry goblin! Once offended, they go to great lengths to seek their revenge. Some of the goblin’s favorite pranks include stealing gold and silver, riding horses into exhaustion during the night, and altering signposts. According to many European fairy tales, a goblin’s bitter smile can also curdle human blood, and his laugh can sour milk and cause fruit to fall from the trees. The only way to get rid of a household goblin is to cover your floors with flaxseed. When he shows up ready to make trouble, he’ll be compelled to first pick up all the seeds—a task that will be impossible to complete before dawn. A few nights of this tiresome business will be enough to convince him to find someone else to bother.

In their guise as bankers and moneylenders, the goblins of Gringotts bear a striking resemblance to a mythical Scandinavian creature known as the

Nis

. According to Scandinavian folklore, these ugly little members of the

dwarf

family are especially skilled at handling money. When a Nis is angry with his human hosts, he often attacks whatever is most essential to their livelihood (killing off the cows on a dairy farm, for example). When he wants to reward them, he presents them with a chest of gold.

It was only in the seventeenth century, when

witch persecution

swept across much of England and Scotland, that goblins became routinely associated with the forces of darkness and evil. Some later English fairy tales try to distinguish between good and bad household spirits by identifying to them as either goblins (who are clearly malicious) or hobgoblins, who are more benign and playful. The most famous hobgoblin by far is the literary character of Robin Goodfellow, also known as Puck, who appeared in dozens of stories and folktales from the late fifteenth century onward.

Well known as a friendly prankster who inhabited households and occasionally performed domestic tasks, in some tales Robin Goodfellow is also the personal servant and errand boy of the

fairy

king Oberon. He is blessed with the power of shape-shifting (see

Transfiguration

) and making wishes come true, and he uses his powers to punish the wicked and reward the good. Puck’s most celebrated appearance is in Shakespeare’s comedy

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

, where he plays cupid to a group of star-crossed lovers lost in an enchanted forest. Laughing at the ridiculous antics of his victims, Puck merrily observes, “Lord, what fools these mortals be!”