The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (63 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

Although sibyls were often described as wild women who lived in caves, many artists preferred to depict them as graceful classical figures

. (

photo credit 69.2

)

According to legend, the Sibyl of Cumae (who lived for hundreds of years) also foresaw the future destiny of the Roman Empire. She offered to sell nine volumes of her prophecies to Tarquin Superbus, the last king of Rome. Tarquin thought the asking price was too high and refused to pay, perhaps expecting the sibyl to bargain. Instead, she burned three of the books. A year later, she returned and offered the remaining six books at the same price. Again Tarquin refused, so the sibyl burned three more volumes. A year later she returned again and this time, yielding to pressure from his advisors and diviners, Tarquin bought the remaining three books, at the original price.

The stories about the Sibyl of Cumae are mythical, but the prophecies attributed to her actually existed. Written in the form of riddles, they were inscribed on palm leaves (by whom no one knows), bound into books, and kept in a heavily guarded stone chest in the Temple of Jupiter in Rome. Known as the

Sibylline Books

, the prophecies were to be consulted only by the Roman Senate, and only in times of disaster or emergency. But, alas, what the books foretold, whether their advice was heeded, or how they affected the fate of the empire, remains unknown. The books were destroyed by fire in 83

A.D

.

We do, however, know the contents of the

Sibylline Oracles

, fourteen volumes of prophecies that came to light between 100

B.C.

and 200

A.D

. and survive to this day. Beginning at the dawn of time, a sibyl tells of the creation of the universe and the Garden of Eden. She chronicles the

giant

wars of Greek mythology, predicts the rise and fall of empires—Egypt, Troy, Greece, Rome, Persia—and foretells the destinies of Alexander the Great, Cleopatra, Jesus of Nazareth, and a succession of Roman emperors. However, the

Sibylline Oracles

were not exactly what they appeared to be. Rather than being the inspired visions of a legendary seer, the prophecies were in fact clever forgeries. The earliest of the prophecies were penned by Jewish authors living in Alexandria, Egypt, who hoped to popularize their teachings in the pagan world by attributing them to the revered sibyls. Christian writers continued the custom by making it appear as if the sibyls had anticipated the coming of Jesus and the advent of Christianity. For centuries, church leaders believed the prophecies were authentic, and the status of the sibyls continued to grow until it equaled that of the Old Testament prophets—a fact that is beautifully documented by their inclusion on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome.

Legend tells that sibyls spoke whenever they were inspired. Oracles, on the other hand, spoke only when spoken to. In the ancient world, an oracle was a religious shrine where a petitioner could seek the advice of the resident deity and receive an answer. The word “oracle” (from the Latin, meaning “to pray” or “to speak”) also referred to the priest or priestess who spoke for the deity, as well the message itself. Greece was the center of oracular wisdom, and its many shrines were consulted by governments, individuals, and foreign emissaries seeking advice on important matters such as the outcome of wars, where to build a temple, how long a ruler might live, or even the reliability of other oracles. An oracle could speak in many ways. At some shrines, the inquirer would spend the night and receive his answer in the form of a

dream

—a method known as incubation. At Zeus’ oracle at Dadona, the god spoke through the rustling of the leaves of the sacred oak tree, as interpreted by the temple priest. The most esteemed oracle was Apollo’s, which operated on the slopes of Mt. Parnassus at Delphi from 1400

B.C.

until 381

A.D

. Here the god spoke through a priestess known as a Pythia, a title derived from the python that Apollo slew to gain the shrine. To receive the answer to an inquiry, the seeker would first fulfill the appropriate rituals and sacrifices and pay the required fee. Then, armed with the question, the Pythia would enter a sacred chamber in the lowest level of the temple. There she would sit on a bronze tripod (a three-legged stool), enter a trance, and become possessed by Apollo, who would answer the question—either directly, or as interpreted by a priest, in poetic verse.

At the Oracle of Delphi, the Pythia would enter a trance and answer questions while possessed by the spirit of Apollo

. (

photo credit 69.3

)

While some oracles spoke clearly, the Delphic Oracle had a reputation—especially in plays and literature—for slippery answers that were not exactly what they seemed to be. When the Roman tyrant Nero visited the site, according to one legend, he was warned that the number 73 would mark his downfall. Being only thirty years old at the time, the emperor, who was contemptuous of the oracle, expected to live a long life. In fact, he committed suicide the following year after being overthrown by the military leader Servius Galba. It was Galba, it turned out, who was seventy-three. Undoubtedly, the best-known story of this type concerns Croesus, the fabulously wealthy king of Lydia who consulted the oracle in the seventh century

B.C.

about his plan to wage war against Persia. The oracle replied that if he did so, “Croesus will destroy a great empire.” Encouraged by this apparent prophecy of victory, the king launched his attack and suffered a calamitous defeat. Taken prisoner, he was allowed to send a messenger to Delphi to inquire why the oracle, on whom he had bestowed many extravagant gifts, had so misled him. The oracle replied that, clearly, it had spoken the truth: a great empire

was

destroyed—his own.

Stories like these—of prophecies that are misinterpreted, or seem to say one thing but mean another, or where the listener fails to recognize the possibility of more than one meaning—can be found in legends and folklore around the world. They also make us wonder if there might not be more than we realize to Sibyl Trelawney’s prophecy concerning a boy whose birthday comes late in July. Are there meanings in the words we can’t quite hear—yet? It is a question that applies to the prophecies of Nostradamus as well.

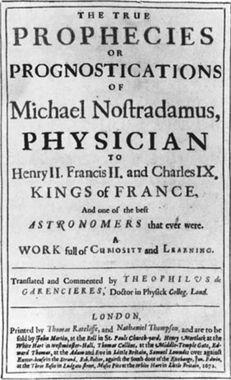

Unlike the sibyls and the ancient Pythias, we know exactly who Nostradamus was. He was born Michel de Nostredame, on December 14, 1503, in St. Rémy, Provence, France. His family was educated and well-off and Michel appears to have been an exceptional child—intelligent, inquisitive, and studious. After enjoying a classical education (studying Greek, Latin, philosophy, rhetoric, mythology, and astrology), he attended medical school and graduated from the University of Montpellier at the age of twenty-six. Following the custom of the day, he then Latinized his name to Nostradamus to reflect his education and status as a physician.

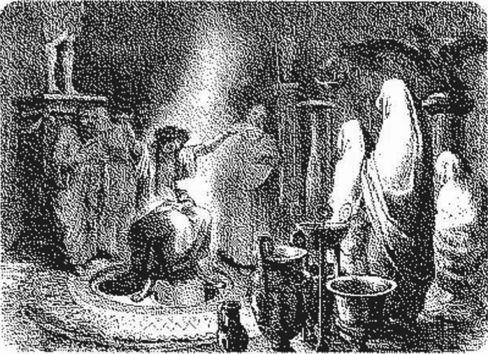

Nostradamus rapidly established himself as a gifted and courageous doctor, especially in his treatment of bubonic plague, which ravaged Europe. While practicing medicine, however, he was also developing his skills as an astrologer and delving into the mysteries of divination. In 1555, he published Volume I of

Centuries

, the book that was to secure his reputation as the most famous seer of all time. Eventually consisting of ten volumes, each book contained one hundred prophecies composed in the form of rhymed verses of four lines known as “quatrains” (the word “centuries” refers to the number of verses in each book, not the span of a hundred years). In his preface to the work, Nostradamus explained his method of prophecy to be a combination of astrology, scrying (see

Crystal Ball

), and, most of all, divine inspiration. Alone in his study in the evening, he would sit on a three-legged stool (as the Pythia did) and stare at a candle flame or peer into a bowl of shimmering water, which he touched with a

magic wand

. Soon a vision would reveal itself and he would write down what he had seen. Later, he would refer to his notes to compose the quatrains, and in the process hide their meaning under layers of obscurity so that only the most scholarly investigators could make sense of them. Nostradamus believed he was laying out the future of the world until the year 3797, and thought that many of his revelations were too shocking to reveal to the general public. He also may have feared the scrutiny of church authorities, who were investigating witchcraft at every turn (see

Witch Persecution

).

The books caused an immediate sensation. The quatrains were highly intriguing, although exceedingly difficult to understand, as they were written in a combination of French, Greek, Latin, Italian, and Hebrew, and contained numerous puns, anagrams, invented words, and mythological references. Nevertheless they were riveting on account of their violent imagery and dire predictions of wars, floods, fire, famine, earthquakes, disease, betrayal, and the collapse of empires. As many Nostradamus students have noted, it is virtually impossible to read the prophecies and understand precisely what they are predicting. The verses give the feeling of saying much while being clear about nothing. It is only

after

an event has occurred that some of the prophecies suddenly appear to reveal their meaning.

The best-known example of a prophecy that was fulfilled during Nostradamus’ lifetime involved the death of Henry II, the King of France. The date was July 1, 1559, and the event was a jousting exhibition held by the royal court in honor of the marriage of Henry’s daughter to Philip II of Spain. The monarch, a noted sportsman, had already ridden twice against the captain of his Scottish guard, the Comte de Montgomery, but neither had unseated the other, and the king insisted on a third round. This time, the Comte’s lance shattered and a shaft of wood penetrated the king’s visor, mortally wounding him in the brain. He died eleven days later. Almost immediately, word flew through the kingdom that Nostradamus had foreseen the event five years earlier. In quatrain 35 of the first book of

Centuries

he had written:

The young lion will overcome the older one,

In a field of combat in single fight:

He will pierce his eyes in their golden cage;

Two wounds in one, and then he dies a cruel death.

To many, the prophecy, once obscure, now seemed clear. The “young lion” referred to the count, who was, indeed, somewhat younger; the “field of combat” was the jousting lists; the “golden cage” referred to the king’s helmet and visor (although it was certainly not made of gold); the fatal wound was above the king’s left eye; and the “cruel death” was indisputable. Nostradamus’ reputation, already strong, was ensured.