The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (62 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

BELLADONNA

Harry is careful to keep his potion-making kit stocked with essence of belladonna, a poisonous plant that has been used for centuries to make a variety of potent concoctions. Also known as deadly nightshade, belladonna is a source of the poison atropine, which in small quantities is used to dilute the pupils of the eye and relieve pain and spasms. In larger amounts, however, it causes death. Historians of ancient Rome and eleventh-century Scotland both tell of using the plant to poison enemy soldiers. In early modern Europe, witches were believed to kill their enemies using potions and ointments made from belladonna and other deadly plants. Some scholars believe that the name belladonna, which is Italian for “beautiful woman,” derives from an old superstition that the plant worked its dark magic by taking the form of an enchantress who was beautiful but deadly to behold. Others, however, believe that the name was bestowed because Italian women used small quantities of the plant’s juice to dilate their pupils, making their eyes appear more brilliant.

MONKSHOOD/WOLFSBANE

Harry’s failure to know that monkshood and wolfsbane are two names for the same plant is one of the first of many humiliations he will suffer at the hands of the potions master, Snape. But his confusion is understandable, since many plants—especially those used for magical or medicinal purposes—have been given numerous names. This particular plant is properly called aconite, and its seeds, leaves, and roots contain the deadly poison aconitine, which slows the heart rate and lowers blood pressure. It has been called monkshood because its leaves are said to resemble the hoods worn by robed monks, and wolfsbane because European farmers once protected their livestock from wolves by putting out meat saturated with the plant’s deadly juices. The plant has a long magical history. In Greek myth, aconite sprouted wherever the ground was dampened by the drool of the three-headed dog, Cerberus (see

Fluffy

). In early modern Europe, witches were thought to have used the plant in potions and in flying ointment (see

Witch

). It was also used in love potions. Unfortunately, because it was hard to get the dosage right, sometimes the beloved ended up deceased!

MOONSTONE

A good essay on the properties of moonstone (a Hogwarts fifth-year homework assignment) would certainly explain that this delicate, milky white stone is a form of feldspar that, according to legend, derives its magical power directly from the moon. Known in European folklore as the “traveler’s stone” because of the magical protection it promised to those on the move, the moonstone was long regarded as a

talisman

of good luck and fertility. In medieval times, carrying the stone was thought to protect one against confusion, insanity, and epilepsy. If placed in the mouth or ground into a potion, it could be used as an aid in decision-making, and, when the moon was full, for predicting the future. Some Eastern cultures held that moonstone was formed from the solidified rays of the moon, and that a good spirit dwelled within.

f the many forms of

f the many forms of

divination

taught by Professor Trelawney, prophecy is not among them. That’s because unlike

crystal-ball

reading,

tea-leaf reading

, or

astrology

, prophecy isn’t a technical subject with procedures that can be taught. Throughout history and in cultures worldwide, prophecy has been viewed as a gift—a divine inspiration that possesses an individual and in a vision, dream, or ecstatic frenzy, reveals to him or her the shape of things to come.

Prophecy has many traditions. Prophets and their prophecies appear in the earliest literature—

The Iliad, The Aeneid

, and the Babylonian

Epic of Gilgamesh

. The tales of King Arthur, Shakespeare’s

Macbeth

, and other classic works use prophecy to create anticipation, mystery, and foreboding in their works, and to ask perplexing questions: Is the future determined? And if we know what’s coming can we change it? Prophecy is also at the heart of many religious traditions, and every culture in the world has its share of doomsday prophets who foresee the end of the world and announce that all sinners must repent.

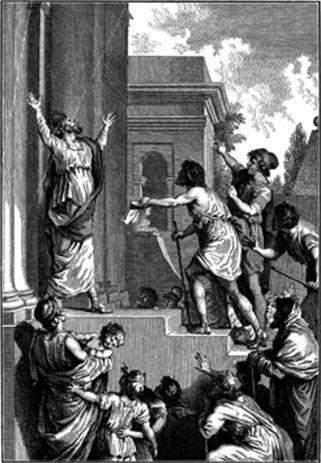

While the word “prophecy” has come to mean “prediction,” foretelling the future has never been the primary role of religious prophets. In the great faiths that arose in the ancient Middle East—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—a prophet was a spokesperson for God. The earliest type of Hebrew prophet was known as a

nabhi

, meaning “a called person.” He was often a strolling musician with a flute or harp, and when inspired he sang and danced and spread the word of God. Over the course of the centuries that followed, the role of the prophet deepened and evolved, leading to a succession of literary prophets such as Amos, Isaiah, and Jeremiah. These visionaries conveyed God’s message in the form of stories, poetry, or sermons that eventually became the prophetic books of the Old Testament. The role of these prophets was to instruct, encourage, chastise, and inspire. When they did lay out a vision of the future, it often entailed long periods of suffering and injustice to be followed at last by a “golden age” when peace, harmony, and absolute justice would prevail. This tradition of Hebrew prophecy was continued by Jesus and Muhammad, the chief prophets of Christianity and Islam, who saw themselves as the natural successors to the Old Testament prophets. Christianity and Islam also share a prophetic vision of the future leading to a period of divine judgment when the wicked will be punished and the virtuous rewarded with eternal life in paradise. All of these figures have come down through history as moral and spiritual leaders whose mission was to reveal the will of God, teach the necessity of righteousness over sin, and shepherd the destiny of nations.

The biblical prophets were moral and spiritual leaders

. (

photo credit 69.1

)

Hogwarts divination teacher and occasional prophet Sibyl Trelawney is aptly named (as is her great-great-grandmother, Cassandra). The earliest prophetesses of legend and literature were sibyls—mysterious women known for their ability to foresee the future while in a trance. Undoubtedly based on historical seers whose identities are lost in the mists of time, sibyls were portrayed by Greek and Roman writers as divinely inspired, cave-dwelling, and often mad. Just as Professor Trelawney predicts the birth of a wizard with the power to vanquish the Dark Lord, ancient sibyls were said to predict the rise and fall of rulers and their empires, as well as wars, storms, famines, and floods.

According to legend, there were ten sibyls in the ancient world, scattered throughout Egypt, Babylonia, Persia, Libya, and Greece. All had different names, but all were called sibyls in honor of the original prophetess of Greek legend whose name was Sibylla, and who was said to be a daughter of Zeus. In his epic tale

The Aeneid

, the poet Virgil created a compelling portrait of the most famous of all sibyls, Amalthea, the Sibyl of Cumae. Emerging from her cave dwelling to greet the Trojan warrior, Aeneas, the sibyl is possessed by the spirit of Apollo, the god of prophecy. Her limbs tremble, her heart pounds, her hair stands on end, and, foaming at the mouth, she speaks in a voice “not human at all” and tells Aeneas what lies ahead: “War, I see, terrible war, and the river Tiber foaming with streams of blood.… You will beg for mercy, be poor, turn everywhere for help. A woman will be the cause once more of so much evil.… Do not yield to evil. Attack, attack, more boldly even than fortune seems to permit. An offering of safety.… will come from a Greek City.”