The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (77 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

eep within the Ministry of Magic, locked in the Department of Mysteries, a tattered, fluttering curtain hangs from an ancient stone archway. When they first approach the ruined arch, Harry and Luna are sure they hear whispered voices from within, just beyond the curtain, or veil. Hermione points out that this is impossible—there is no space within the archway to hide unseen speakers. Yet for Harry there is something both disturbing and oddly captivating about the gently moving veil, although its purpose is initially obscure. It is not until after he suffers the loss of the most important person in his life that the meaning of the veiled doorway becomes chillingly clear. It is nothing less than a portal between life and death. On one side is the world as we know it, on the other, the impenetrable mystery of what lies beyond.

eep within the Ministry of Magic, locked in the Department of Mysteries, a tattered, fluttering curtain hangs from an ancient stone archway. When they first approach the ruined arch, Harry and Luna are sure they hear whispered voices from within, just beyond the curtain, or veil. Hermione points out that this is impossible—there is no space within the archway to hide unseen speakers. Yet for Harry there is something both disturbing and oddly captivating about the gently moving veil, although its purpose is initially obscure. It is not until after he suffers the loss of the most important person in his life that the meaning of the veiled doorway becomes chillingly clear. It is nothing less than a portal between life and death. On one side is the world as we know it, on the other, the impenetrable mystery of what lies beyond.

The use of a veil to represent the threshold between this life and the next originated in biblical times and was still popularly known in the nineteenth century, when people often used the phrase “beyond the veil” to refer to the spiritual world inhabited by those who had passed away. In ancient Jerusalem, “the veil” referred to a beautiful cloth that separated the main area of the Hebrew temple from a sacred room that housed the Ark of the Covenant and the stone tablets of the Ten Commandments. This room, known as “the Holy of Holies,” was considered so awesome and filled with God’s presence that only the high priest was permitted to enter, and then only on the holiest day of the year (the Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur). There he would pray on Israel’s behalf and utter the sacred name of God, which could be spoken only on that day. This ritual was believed to be very dangerous, for if any false or sinful thought entered the mind of the priest, the world would be destroyed. Thus the original temple veil was believed to separate two profoundly different worlds. On the one side was the known, the everyday, the ephemeral; on the other was the mysterious, the eternal, the divine, or heaven.

By the time the New Testament was written in the first century

A.D

., the veil had come to represent a boundary between the world of the living and the world of the dead. The Book of Matthew relates how at the moment of Jesus’ death, the veil of the temple “was torn in two, from top to bottom, and the earth shook, and the rocks were split; tombs also were opened, and many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised, and … they went into the holy city and appeared to many.” Centuries later, this idea of the veil would capture the imagination of several generations of British and American men and women who longed for a way to communicate with their lost loved ones.

Belief in an afterlife is very old (going back at least to Neanderthal man, 10,000 years ago), as is the belief in the possibility of making contact with the deceased, or “spirits.” In biblical times and throughout much of European history, trying to make contact with the departed was considered part of the

dark arts

and was forbidden by religious authorities. By the nineteenth century, however, this long-standing prohibition had begun to fade. In 1848, young sisters Margaret and Kate Fox of Hydesville, New York, startled the world with claims that they could communicate with the spirits by asking questions and interpreting the series of knocking sounds they heard in response. Thousands of people were willing to believe their story and eager to try their own hand at contacting those beyond the veil.

During the heyday of the popular nineteenth-century movement known as spiritualism, as many as 11 million people from all walks of life became convinced of the authenticity of spirit contact, and many swore that they had experienced it firsthand. In his book

Life Beyond the Veil

, the Reverend Vale Owen explained that the information about the afterlife in his multivolume work had been transmitted to him by six different spirits, including his mother; his daughter (who had died at age fifteen months); an eighteenth-century British schoolmaster named Astriel; a seamstress from Liverpool, England, named Kathleen; and two others named Arnel and Zabdiel. According to Owen, these spirits projected images “through the veil” and into his own mind, so that he could transcribe them for posterity. Many other books and essays were reportedly written using this method, with spirits relaying messages to their earthly scribes. Even Mark Twain allegedly wrote a novel from the hereafter and communicated it to two women via a ouija board. However, Twain’s daughter Clara Clemens was unconvinced and went to court to halt the novel’s publication.

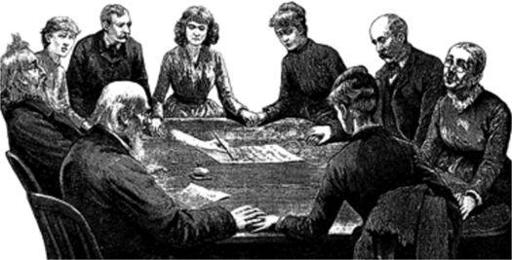

During the heyday of spiritualism in the nineteenth century, people gatherered around séance tables in an attempt to contact loved ones “beyond the veil.”

(

photo credit 88.1

)

Once it became evident that communicating with the dead could be highly profitable, hundreds of individuals discovered their ability to cross the veil and commune with spirits. Mediums hung out shingles and advertised their services in daily newspapers. As people flocked to séances, simple rapping sounds were replaced by more dramatic evidence of contact with the spirit world. At some séances, mediums took on personalities and voices quite unlike their own as the spirits of the departed spoke through them. In darkened rooms invisible forces rang bells, shook tambourines, levitated tables, moved furniture, wrote messages on school slates, and even flitted over the heads of the audience. All of this, as skeptics were quick to discover, was accomplished through trickery. Indeed, forty years after the fact, Margaret Fox admitted that the knocking sounds she and her sister had claimed were spirits had in fact been made by the two girls cracking their toe joints!

That the spiritualist movement was largely started and sustained by fraud does not necessarily mean that all of its phenomena are fraudulent. There were many sincere mediums who genuinely believed in their own powers. Sincere spiritualists founded newspapers and journals, sponsored public meetings where speakers delivered lectures on such topics as the landscape of heaven and daily life in the hereafter, and allied themselves with social causes of the day, including women’s rights and the abolition of slavery.

The attractions of spiritualism are easy to understand: the burning desire to contact a departed loved one and the uplifting message that there was life everlasting. While spiritualism is not the craze it once was, the desire to know what lies on the other side of the veil is still apparent. Mediums today still hold séances, publish best-selling books, have television shows, and claim to speak for the dead. And skeptics still counter with arguments about deception and how the mediums’ work is

really

done. In the end, it seems, people believe what they want to believe. And deep within the Ministry of Magic, somewhere in the Department of Mysteries, scholarly wizards scrutinize an ancient stone archway and fluttering veil hoping to discover what Nearly Headless Nick calls “the secrets of death.” Even wizards, it seems, don’t know everything.

n folklore from around the world, a werewolf is a human with the capacity to transform into an unusually ferocious wolf. Active only at night and often (but not always) under a full moon, he devours men, women, children, and livestock, ripping out their throats with his claws and fangs. In some stories, a man who becomes a werewolf is the unwilling victim of bad genes, a

n folklore from around the world, a werewolf is a human with the capacity to transform into an unusually ferocious wolf. Active only at night and often (but not always) under a full moon, he devours men, women, children, and livestock, ripping out their throats with his claws and fangs. In some stories, a man who becomes a werewolf is the unwilling victim of bad genes, a

curse

, or the bite of another werewolf. Remus Lupin, who was bitten as a child by Fenrir Greyback (a particularly savage werewolf who feels duty-bound to bite as many people as possible), falls into this category. These involuntary werewolves usually loathe the harm they cause, but are powerless to stop their transformation and subsequent actions. But in other stories, a

sorcerer

makes a conscious decision to become a werewolf—often by using an enchanted belt or special ointment—so that he can carry out his terrible deeds, usually in league with the Devil. Although werewolves are almost always men, tales of female and child werewolves also exist.