The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (75 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

ew animals, real or imaginary, have captured the imagination as consistently as the unicorn. Ever since the single-horned creature was first described more than two thousand years ago by the Greek physician Ctesias, people have written about, painted, sculpted, and hunted unicorns—all the while arguing about whether they really exist.

ew animals, real or imaginary, have captured the imagination as consistently as the unicorn. Ever since the single-horned creature was first described more than two thousand years ago by the Greek physician Ctesias, people have written about, painted, sculpted, and hunted unicorns—all the while arguing about whether they really exist.

The unicorns described in antiquity bear only slight resemblance to the noble, innocent, and pure creatures that inhabit the

Forbidden Forest

at Hogwarts. According to Ctesias, the unicorn was native to India. It was about the size of a donkey, had a dark red head, a white body, blue eyes, and a single horn, about eighteen inches long, extending from its forehead. White at the base, black in the middle, and flaming red at the top, the horn had a remarkable quality. When separated from its owner and made into a drinking cup, it protected all who drank from it from poisons, convulsions, and epilepsy. Such vessels were not easy to come by, however, since the speed, strength, and vicious temperament of the unicorn made it almost impossible to capture.

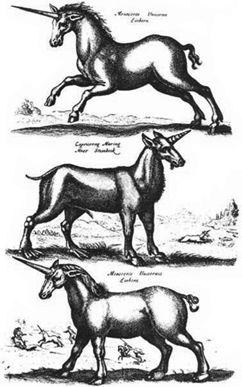

Over the next several centuries, belief in the elusive creature grew, though evidence of its existence was still wanting. Aristotle and Julius Caesar both described one-horned animals and were cited as authorities. The Roman naturalist Pliny added new details to the unicorn’s appearance, giving it a deer’s head, elephant’s feet, a boar’s tail, and a three-foot-long black horn. (Later writers suggest that early unicorn reports were based on misleading descriptions of the Indian rhinoceros, or on sightings of two-horned animals such as goats or ibex that were either viewed in profile or had lost a horn). Pliny also confirmed the unicorn’s ferocious nature and said the beast had a deep, bellowing voice.

By the Middle Ages, the popular image of the unicorn had evolved from the collage of animal parts described by the ancients to the graceful creature we recognize today. Paintings and tapestries of the period portray a beautiful, white, horse-like animal with a spiraling, pure white horn and the cloven hoofs of a deer. In literature, the unicorn came to represent strength, power, and purity. It was incorporated into Christ ian symbolism and became part of the royal coat of arms of England and Scotland. Unicorns appeared in Arthurian legend, fairy tales, and romanticized accounts of the exploits of Genghis Khan and Alexander the Great.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, European travelers returned from Asia, Africa, and the Americas with new reports of unicorn sightings. Since descriptions differed, unicorns were assumed to come in several varieties

. (

photo credit 85.1

)

A typical medieval story emphasizing the purity of the unicorn tells of a group of forest animals that came to a pool to drink but found the water poisoned. The thirsty animals were saved when a unicorn appeared and dipped his horn into the water, causing it to become fresh and untainted. So great is the unicorn’s love of all things innocent and pure, according to another tale, that when a unicorn comes upon an innocent maiden sitting beneath a tree, he will lay his head in her lap and fall asleep. This idea greatly appealed to those interested in capturing unicorns to relieve them of their valuable horns. Unicorn hunting was a fearsome business, since the animals were rumored to be able to use their horns as swords and, if pursued, would jump off cliffs, landing on their horns and walking away unscathed. A safer and less strenuous approach, it seemed, would be to use a virtuous maiden as bait. Once the unicorn was asleep in her lap, the waiting hunters could move in and capture him.

Interest in catching unicorns finally died out in the eighteenth century, as numerous skeptics pointed out that it was impossible to find anyone who had actually

seen

one of the creatures with his own eyes. A few writers persisted in including unicorns in their books of natural history, repeating ancient and medieval accounts, but most became convinced that it was time to retire the animal to the realm of fable. This hardly dampened popular enthusiasm for the unicorn, which lived on in art, literature, and imagination, as it does to this day.

hornswoggle

(hôrn ′swog′ əl) tr.v.

-gled, -gling, -gles

. To bamboozle; deceive. [Origin unknown.]

Impossible as it was in the sixteenth century to find anyone who had seen a unicorn, locating a unicorn horn was another story altogether. That’s because unicorn horn was for sale in every apothecary shop (the equivalent of today’s pharmacy) as a cure for most diseases and a protection against poisons. Demand was great and prices were sky high. Ground into a powder the horn—also known as “alicorn”—could be taken in pure form or combined with other medicinal agents. Those unable to afford the precious product could instead purchase a vial of water into which a unicorn’s horn had allegedly been dipped.

Of course, the product sold in apothecary shops did not really come from unicorns. Instead, it was the tusk of the narwhal, a species of arctic whale that has a single, twisted horn that can grow up to nine feet long. As the number of whaling expeditions grew in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, so, too, did the supply of supposed unicorn horn. Tests to verify the authenticity of alicorn—most of which involved placing spiders near the horn and observing their reactions—were numerous, but apparently few detected bogus horn, for narwhal tusks, masquerading as unicorn horn, made their way into shops across Europe.

Not all alicorn was consumed in medicine. The legendary property of unicorn horn cups to neutralize poisons, first reported by Ctesias more than one thousand years earlier, continued to make them a highly valued possession, especially among royalty, for whom fear of poisoning was a daily fact of life. Alicorn cups were so valuable that in 1565 King Frederick II of Denmark was able to use just one as security for a loan to finance a war against Sweden.

Seventeenth-century drawing of a narwhal, the arctic whale whose spiraled tusk was sold at a hefty price as unicorn horn. The present-day narwhal population is estimated at 25,000 to 45,000

. (

photo credit 85.2

)