The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (71 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

lthough Hogwarts students eagerly purchase talismans to protect themselves against a mysterious epidemic of

lthough Hogwarts students eagerly purchase talismans to protect themselves against a mysterious epidemic of

petrification

, these powerful objects are more commonly used to perform magic than to ward it off. Unlike

amulets

, which are specifically designed to keep the wearer safe from harm, talismans are valued for their ability to produce supernatural transformations—making their owners invisible, inhumanly strong, immune to disease, or able to remember every word a teacher says. A talisman can be any kind of object—a statue, a book, a ring, an item of clothing, a strip of metal, or a piece of parchment. Even the rotting newt’s tail purchased by a panicked Neville Longbottom can be a talisman if it has magic powers. Some objects, such as gemstones, have traditionally been viewed as magical by nature. But throughout history most talismans have been purposefully endowed with their potency through rituals intended to harness the forces of nature or the power of gods. Many were inscribed with

magic words

, the names or images of deities, or brief

charms

.

Talismans were very much in demand in the ancient world. Archaeologists have discovered papyrus talismans from ancient Egypt, as well as hundreds of stone and metal talismans throughout the Mediterranean region. Especially popular for curing illness, they also were used to attract love, improve memory, and ensure success in politics, sports, or gambling.

In medieval times, there was a talisman for just about any purpose you could think of. Tying a hare’s foot to the left arm was said to enable a person to venture into dangerous territory without risk of harm. Carrying mistletoe would prevent a guilty verdict for those on trial. Possessing a sprig of the herb heliotrope bundled with a wolf’s tooth and wrapped in laurel leaves would stop people from gossiping about you. So great was the belief in the power of talismans in fourteenth-century England that rules for dueling were revised to require that each participant swear that he was not carrying a magic ring, stone, or other talisman that would give him an unfair advantage.

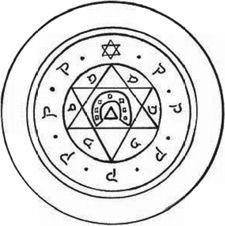

A medieval talisman said to provide its owner with good luck and the ability to make wise decisions when gambling

. (

photo credit 80.1

)

Because the heavenly bodies were thought to hold sway over earthly life (see

Astrology

), many talismans were designed to capture the influence of a particular planet. Someone who wanted to succeed in combat, for example, might make a talisman to harness the influence of the planet Mars, which was said to govern bodily strength. The talisman would be fashioned from iron (the metal traditionally associated with Mars) at a time when Mars was believed to radiate its power most intensely. It might also be engraved with the planet’s special number, five, or painted Mars’ color, red.

Such astrological talismans were especially popular among Renaissance alchemists, who followed elaborate rituals to make objects they hoped would help them to transform base metals into gold. After waiting for the right celestial moment to arrive, they would recite incantations to summon spirits or

demons

who they hoped would endow their talismans with the necessary power. The

Sorcerer’s Stone

, which was believed to offer eternal life as well as endless wealth, was the most desirable talisman of all.

Talismans remained popular into the nineteenth century, when one all-purpose talisman engraved on silver during the proper phase of the moon was said to be able to make the owner healthy, wealthy, pleasant, cheerful, honored by others, and able to make all journeys safely. Although people today are not likely to engrave magic words on metal, those who carry a rabbit’s foot or insist on wearing their “lucky socks” to every playoff game keep the use of talismans alive.

here Ron sees an innocent bowler hat, Professor Trelawney sees a menacing club. Where he sees a sheep, she sees a terrible black dog known as a

here Ron sees an innocent bowler hat, Professor Trelawney sees a menacing club. Where he sees a sheep, she sees a terrible black dog known as a

grim

. Both are staring into the bottom of Harry’s teacup, practicing a popular form of

divination

called

tasseomancy

, or tea-leaf reading.

The custom of telling fortunes by examining tea leaves began in China, probably during the sixth century. Tea was unknown in the West until 1609, when Dutch traders began importing it from the Orient. Although the new beverage was initially regarded with suspicion, people were drinking it in France by 1636, and in 1650 it arrived at the shops in England, where it would eventually become a much-loved staple of daily life. By the middle of the seventeenth century, tea consumption was widespread, and tea leaves were being read by fortune-tellers across much of Europe.

The concepts behind tea-leaf reading were not entirely new to Europeans, since the ancient Romans had told fortunes by

oinomancy

—the interpretation of sediment left in the bottom of a wine cup—and medieval diviners had studied the patterns made by melting wax, molten lead, and other substances. But the new art did require knowledge of how to prepare a teacup for a reading, as well as mastery of the meanings of dozens, if not hundreds, of images that might appear in the cup. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, easily accessible booklets provided the curious with instruction in all aspects of tasseomancy (from the Arabic

tass

, meaning “cup,” and the Greek

mancy

, meaning “prophecy”). As a result, the practice became common not only in the back rooms of fortune-tellers, but also in the parlors of the well-to-do.

Methods for reading tea leaves vary somewhat in their details, but the procedure described here is representative of most approaches. Tea (ideally a dark-colored Chinese or Indian variety) is brewed from loose leaves and poured into a light-colored cup without the use of a strainer. The person whose fortune is being told drinks the tea, leaving a small amount of liquid and all of the leaves at the bottom. After swirling the remains around three times, he or she turns the cup upside down on a saucer and taps the bottom three times so that most of the leaves fall out. The reader then picks up the cup and examines the pattern of leaves that remain stuck to the base and sides.