The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (82 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

n Nepal, it is called a

n Nepal, it is called a

rakshasa

, the Sanskrit word for

“demon.”

If you live in Canada, you might call it a

sasquatch

(Native American for “hairy man”), while in the United States it’s known simply as

Bigfoot

. Its proper name, however, is “yeti,” and it has allegedly stalked the Earth for millennia. Accounts of its existence date from as early as the fourth century

B.C.

and persist to this day. Many people claim to have seen one, yet there’s little evidence to suggest that the creature is real. But if there’s one expert to consult, it’s probably Rubeus Hagrid, for in the language of Tibet

yeti

means “magical creature.”

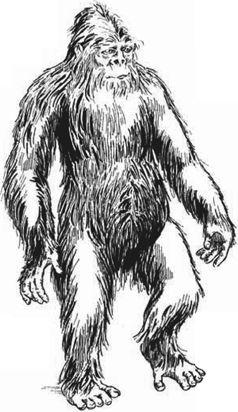

According to most lore, the typical yeti is seven to ten feet tall, with long arms, an ape-like face, and a flat nose. Young members of the species are covered with a thick layer of red hair, which turns black as they grow into adulthood. Tremendously strong, yetis are said to be able to toss around boulders like softballs. They are also remarkably quick on their big feet—twice as fast as the most accomplished human sprinters. They communicate with loud roars and whistling noises. Unfortunately, the yeti isn’t terribly fond of personal hygiene; virtually every legend emphasizes the creature’s overwhelming odor, which is said to be bad enough to curl your hair and make your eyes water.

With such a distinctive appearance, you might expect that it would be easy to find a yeti. But even Professor Gilderoy Lockhart, who claimed to have spent

A Year with the Yeti

, probably fared no better than most yeti seekers. First of all, the yeti is notoriously shy, and hundreds of expeditions aimed at locating the creature have produced only blurred photographs and footprints, most of them regarded as hoaxes. Sir Edmund Hillary, the English explorer who was the first person to reach the summit of Mount Everest, conducted an extensive search of the Himalayas for the elusive creature (dubbed the “Abominable Snowman” by newspaper reporters). All he could find was an enormous skull and some footprints of a size not carried at your local shoe store.

Furthermore, the locations frequented by the yeti are not exactly hospitable. The creatures have reportedly been spotted in pleasant parts of Australia (where locals call them

Yowies

), Canada’s Queen Charlotte Islands (where they are called

Gogete

and are believed to predate humanity), the Middle East, and most recently Spalding, Idaho. But the places the yeti most often makes its home—the Rocky Mountains, the Himalayas, and the Australian outback—are marked by harsh conditions not welcoming to human travelers.

The final obstacle is the fact that the creatures are not known to be the most gracious hosts. Some accounts suggest that the yeti is quite gentle unless threatened, but others describe aggressive behavior in response to people. Former United States President Teddy Roosevelt told of the experience of a trapper friend who ventured into yeti territory with his partner. The creature, frightened of the campfire, loitered in the nearby forest but did not approach the trappers for a few days. Eventually, however, it overcame its apprehension and set upon them; one died a rather unpleasant death, and the other was fortunate to escape to tell the tale.

So if you should be wandering in the Himalayas some snowy afternoon, and you see a flash of red fur and smell a sweet scent that reminds you of rotting garbage, take a moment to wave politely; you

are

in the presence of a celebrity, after all. Then pack your bags and be on your way. The yeti may be nothing but a gentle “magical creature,” but you can never be too careful.

hen Professor Quirrell boasts that he got his turban as a thank-you gift for driving off a bothersome zombie, many of his students have their doubts. For one thing, his unusual headgear reeks of garlic, a sign that it may really be designed to protect its owner from

hen Professor Quirrell boasts that he got his turban as a thank-you gift for driving off a bothersome zombie, many of his students have their doubts. For one thing, his unusual headgear reeks of garlic, a sign that it may really be designed to protect its owner from

vampires

. For another, the good professor quickly changes the subject when asked just how he fought the zombie. It’s a question any qualified Defense Against the Dark Arts instructor should be able to answer, since the zombie is the creation of one of the most malicious of black magicians, the voodoo

sorcerer

.

A zombie is essentially a walking corpse—a being that looks human but has no mind, soul, or will and acts at the command of its creator. Incapable of feeling pain, fear, or remorse, the zombie is a dangerous weapon for any practitioner of the

Dark Arts

. Although there’s no evidence that zombies really exist, zombie legends abound wherever the voodoo religion is practiced.

Voodoo, also known as

vodoun

, is a system of religious beliefs developed by slaves brought from Africa to Haiti during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Magical rites are an integral part of voodoo, often for purposes of worship or healing, but also for harming enemies or gaining power. People who work harmful magic, known as

bokors

, are said to create zombies to be their slaves. Some zombies are allegedly put to work as menial laborers and farm workers, while others have reportedly held office jobs. The most wicked bokors, however, may turn their zombies to darker purposes, using them to destroy the property of enemies or even to commit murder.

According to tradition, a bokor may make a zombie from either a living human or a corpse. In some accounts, the bokor gives the victim a

potion

to induce a deep coma. Believed dead, the victim is buried by his family, only to be dug up soon afterward by the bokor. A second potion makes the victim walk, talk, and breathe again, but leaves him under the bokor’s complete control. In other accounts, the bokor actually murders the victim or steals the body of someone who has recently died. After capturing the person’s soul, which in voodoo is believed to remain with the body at least for a short period of time, the bokor is said to use

spells

to magically restore the body to life as a zombie. Whatever the method, attempting to create a zombie is still viewed today as an evil act throughout the Caribbean islands. In fact, current Haitian law defines zombie making as murder, subject to the same penalties as any other killing.

Fear of being made into a zombie was widespread in Haiti for centuries and may still exist today. Relatives often buried their deceased with a knife to be used to stab an intruding bokor. Some folklore advised filling an occupied coffin with seeds which, according to tradition, a bokor must count before removing the body. If there are enough seeds, the bokor will fail to complete his count before the sun comes up and will be unable to perform his ritual, since dark magic cannot be done during the daylight.

Getting rid of a zombie is a challenge. Although some are said to be slow of speech, moving listlessly and generally behaving like dullards (from which we get the phrase, “acting like a zombie”), a well-made zombie is said to be indistinguishable from an ordinary human and may respond quickly to its bokor’s demands. As Professor Quirrell may or may not know, some traditions hold that sprinkling salt on a zombie will cause it to return to its grave (and presumably also free a live zombie from its mindless stupor). Inferi, the loathsome, zombie-like creatures that Voltemort uses to do his bidding, can be fended off with fire. Alternately, one can appeal for divine intervention. Ghede, the Haitian god of the dead, is said to abhor zombies and may be persuaded to restore them to life by returning their souls. Failing that, however, the best chance of vanquishing a zombie is probably to defeat the bokor that created it. Like many evil beings, a zombie is only as dangerous as the commands it receives from its master.