The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (79 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

Many people believed that witches could change the weather. In this fifteenth-century woodcut, a snake and a rooster are tossed into a cauldron to cause a hailstorm

. (

photo credit 90.2

)

These local wise women were among the first to be accused during the witchcraft panic that spread through western Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Soon, however, accusations of witchcraft began to include women and men from all walks of life. Defined as heretics (enemies of the Christian church) and Devil worshippers, accused witches were blamed for everything from crop failures to sudden infant death to the spread of disease among livestock. Witches were said to associate with

demons

and to participate regularly in horrific acts of ritual murder, vampirism, and cannibalism. According to popular lore, they held frequent

Sabbats

—wild nighttime gatherings in secluded fields or woods—where they praised the Devil with feasting and dancing. Air travel was allegedly the most common mode of transportation to these parties, either by broomstick or on the back of a demon or animal companion known as a familiar.

Such wild imaginings sparked a wealth of literature on witches, and by the end of the

witch persecution

era in the early eighteenth century, the stereotypical witch was fairly well defined. Weather-beaten and wrinkled, she usually had a hooked nose and pointed chin, scraggly hair, and fleshy, drooping lips. She was poor, had a reputation for eccentric behavior, and a fondness for cats. Like the witch of the Grimm’s fairy tale “Hansel and Gretel,” she was likely to live in a small cottage in some out-of-the-way place. In many cases this image was mirrored in reality, since witch hunters sought out easy targets and were quick to accuse old women who lived alone and were already partially cast out of the community. Although charges of witchcraft were not limited to the old and ugly (many accused witches were young, attractive, and prosperous), the stereotypical image of the witch has remained largely unchanged since the eighteenth century.

Witches may have been social outcasts, but according to popular belief they were not without companionship. Each witch was said to possess at least one “familiar”—a

demon

in the shape of a small animal who would offer her advice and carry out malicious errands, including murder, at her command.

Cats

, dogs,

toads

, rabbits, blackbirds, and crows were the most common familiars, but an occasional witch was accused of keeping a hedgehog, weasel, ferret, mole, mouse, rat, bee, or grasshopper as her demonic pet.

Having supposedly received their familiars directly from the Devil, witches were said to bestow tender care upon them, baptizing and naming them (Pyewackit, Gibbe, Rutterkin, Greedigut, or Elemauzer, for example) and offering them the best tidbits of food. A job well done was traditionally rewarded with a few drops of the mistress’s blood.

Familiars became a standard part of witch lore during the English and Scottish witch trials of the sixteenth century and eventually made their way to the American colonies as well. It was widely believed that familiars served as witches’ spies and did much of their dirty work, even casting

spells

and working

curses

. Thus, when someone saw a cat or dog they didn’t recognize, especially if it seemed to look at them in an odd way, they had cause to worry that it was a witch’s trusty servant out to cause them harm.

When the time came for an accused witch’s trial, her supposedly loyal familiar nearly always managed to be missing. This was fortunate for the hapless pet, since those few demons in disguise who were caught were immediately executed.

t would be nice to think that Bathilda Bagshot’s

t would be nice to think that Bathilda Bagshot’s

History of Magic

told the whole story of witch persecution in early modern Europe. There Harry reads that

witches

and

wizards

who were burned at the stake suffered no pain—instead, a simple

charm

made the flames feel like a pleasant tickle. But the good Ms. Bagshot is silent on the fate of the thousands of ordinary women and men who were falsely accused of witchcraft and had no magic powers to protect them. Sadly, such people were the true casualties of the witch hunting hysteria that gripped much of Europe from the middle of the fifteenth century until the end of the seventeenth century.

For roughly 250 years, people at all levels of society were convinced that a vast conspiracy of witches threatened their lives. Malicious individuals devoted to the overthrow of Christianity were believed to be doing the Devil’s work everywhere, from the dairy barn to the royal chambers. Traditional legal and ethical standards were set aside as zealous judges and religious leaders strove to root out the evildoers and exterminate all witches from the face of the earth. Modern scholars estimate that during this period anywhere from 30,000 to as many as several hundred thousand people were viciously tortured and executed as witches, on the basis of evidence that was flimsy at best, and often nonexistent.

Why did these horrific events take place? No one can say for sure. But certainly religious conflict, including the division of the Christian church into opposing Catholic and Protestant camps, played a large role in creating an atmosphere of mistrust among neighbors, and even within families. Also important was the invention of the printing press in the mid-1400s, which allowed for the rapid spread of ideas and fears about witchcraft among people in positions of power.

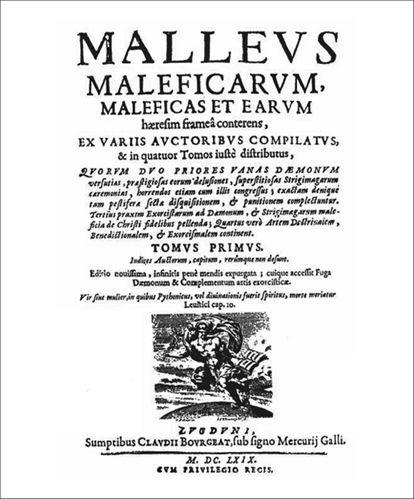

Many of these ideas could be found in the

Malleus Maleficarum

, or

Hammer of Witches

, a comprehensive guide to identifying, prosecuting, and punishing witches written by two German witch hunters in 1486. The book was an immediate success, read by churchmen, lawmakers, and just about anyone who could read. It was so popular that, for nearly two hundred years, it was second only to the Bible in sales. Although the book did not create the phenomenon of witch persecution, by popularizing and supporting the beliefs that lay behind the witch trials, the

Malleus

helped perpetuate the stereotypes and misinformation that condemned thousands of innocent people to death.