The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (69 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

Of course, the spells of fairy tales and literature required no such devices. A simple flick of a wizard’s wand could turn a timid poet into a brave knight or make a horse-drawn carriage take to the air and fly. At Hogwarts, professors can keep students honest simply by subjecting their quills to an anti-cheating spell at exam time. Today, we still use the word “spellbound” to indicate the sense of delighted fascination that such tales evoke.

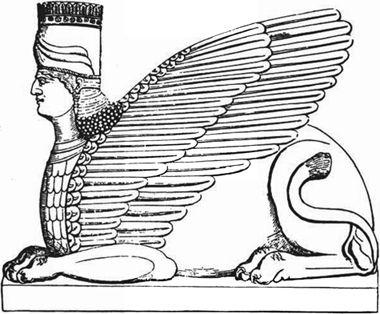

t’s hard to find a monster with a longer history than the sphinx. A majestic creature with the body of a lion and the head and bust of a human, the sphinx has been the stuff of legends for over five thousand years. In ancient Egypt, where it was first introduced, the sphinx was a symbol of royalty, fertility, and life after death. Its image was often associated with the annual flooding of the Nile, which brought life to the parched Egypt ian desert, and statues of sphinxes were placed outside most Egyptian tombs and temples.

t’s hard to find a monster with a longer history than the sphinx. A majestic creature with the body of a lion and the head and bust of a human, the sphinx has been the stuff of legends for over five thousand years. In ancient Egypt, where it was first introduced, the sphinx was a symbol of royalty, fertility, and life after death. Its image was often associated with the annual flooding of the Nile, which brought life to the parched Egypt ian desert, and statues of sphinxes were placed outside most Egyptian tombs and temples.

The most celebrated of the Egyptian sphinx statues is the 240-foot-long, 66-foot-high Great Sphinx, which lies on a strip of desert known as the Giza Plateau. More than 4,500 years old, this colossal limestone carving joins the rippling, powerful body of a lion with the regal head of an Egyptian pharaoh, or king. Most historians believe it is a tribute to the ancient Egyptian ruler Khafre, whose pyramid sits nearby.

From ancient Egypt, the myth of the sphinx made its way across the Mediterranean Sea to the lands of Mesopotamia (modern-day Syria and Iraq) and ancient Greece. In these countries, the half-man, half-lion took on a more sinister meaning, often representing not just the underworld, but also senseless violence and destruction. The throne of the Greek god Zeus at Olympia, the holy mountain on which the gods resided, was supposedly engraved with a ring of sphinxes, shown carrying off small children. Other Greek and Roman sphinxes were depicted as tearing apart their victims or slavering over their mangled remains. The basic anatomy of the sphinx also changed as it moved northeast: In Mesopotamia the mythical beast was often shown with the head of a ram or an eagle; in Greece it was given wings, and the face and breasts of a woman.

Although she lacks wings, the sphinx that Harry Potter encounters during the Triwizard Tournament is probably Greek in character. Not only does she have a woman’s face, she uses her wits to defend a dark secret, much like the sphinx in the ancient Greek myth of Oedipus. In that story, a menacing sphinx stalks the countryside around the city of Thebes, posing impossible questions to travelers and eating them if they fail her test. She finally meets her match in the young wanderer Oedipus, who solves the riddle “What animal walks on four legs in the morning, two in the afternoon, and three at night?” (The answer, of course, is man, who crawls as an infant, walks as an adult, and leans on a cane in his final years.) Having successfully defeated the sphinx, Oedipus, like Harry, is allowed to proceed to his final destination, where a fate even darker than Lord Voldemort’s wrath awaits him.

Over time, the Greek image of the sphinx as a dark and enigmatic creature has become the most prominent. The word itself comes from the Greek

sphingein

, meaning to “squeeze,” “strangle,” or “bind.” Despite the claims of some medieval writers, there is no evidence to suggest that the ancient Egyptians, Mesopotamians, or Greeks believed the sphinx was a real animal. Their legends, artwork, and literature consistently present it as a mythical creature, symbolizing power and forbidden knowledge. This did not stop later writers, such as the seventeenth-century zoologist Edward Topsell, from claiming that the sphinx was descended from a bizarre Ethiopian ape. In honor of such misguided scientific observations, there is now a species of ape called the Sphinx, or Sphinga, baboon.

f all the creatures Harry meets in the forbidden forest, none is quite as terrifying as Aragog, the giant acromantula with a hearty appetite for “fresh meat,” in the form of human flesh. Hagrid, on the other hand, loves the creature, having raised him from egghood and even arranged his marriage. Such starkly contrasting responses are typical of how people around the world feel about these eight-legged wonders. For some, spiders are extraordinary creatures deserving our highest respect. For others, like Ron, the mere sight of one is enough to set off spasms of fear and panic.

f all the creatures Harry meets in the forbidden forest, none is quite as terrifying as Aragog, the giant acromantula with a hearty appetite for “fresh meat,” in the form of human flesh. Hagrid, on the other hand, loves the creature, having raised him from egghood and even arranged his marriage. Such starkly contrasting responses are typical of how people around the world feel about these eight-legged wonders. For some, spiders are extraordinary creatures deserving our highest respect. For others, like Ron, the mere sight of one is enough to set off spasms of fear and panic.

Although few spiders are actually harmful to man, irrational fear of them (known as

arachnophobia

) is common. Reports from ancient times to modern describe people who become terrified, hysterical, or rooted to the ground in the presence of a spider. Others refuse to enter a room until someone else has checked it out for spiders. Such fears may be innate, such as the fear of darkness or heights, but they may also have evolved from past beliefs. During the Middle Ages, many people believed spiders were toxic creatures that infected everything they touched—poisoning food and water, spreading disease, and causing epidemics such as the black plague. (It was not until the nineteenth century that the transmitters of plague were identified as fleas, carried by rats.) In Italy, the bite of a large spider was said to cause the victim to become insane—alternately crying, laughing, trembling, and dancing incessantly. Eventually, this disorder, known as

tarantism

, was recognized as a form of hysteria not caused by spiders.

Spiders are highly efficient predators, however, and their methods of capturing and devouring prey are enough to make some humans shudder. While some spiders trap their victims in webs, others throw silk nets

over

their prey, or pop out of underground borrows and pounce. They then inject the victims with paralyzing venom, dissolve their innards with an enzyme, and drink them like soup, leaving nothing but an empty husk.

So what’s to admire about spiders? Actually, quite a bit. They are extraordinary architects, spinning complex webs that serve as both homes and nets to capture prey. Their silk is one of the strongest substances in the world, by weight far stronger than steel. Female spiders, like Mosag, Aragog’s wife, are caring mothers, giving birth to hundreds of offspring that they carry around on their backs until the young are ready to fend for themselves. Having a few spiders around the house can reduce the presence of annoying and disease-carrying insects, such as mosquitoes and flies. And research is underway for applications of spider venom as a treatment for cardiac arrhythmia and strokes as well as use as a natural pesticide with no adverse effects on humans.

The spider also holds prominent place in many world mythologies. As master web spinners, spiders are credited with the invention of weaving, basket making, and creating fishing nets. In the creation myths of Native American peoples, a figure known as Spider Woman spins the web on which the world hangs and fashions mankind from clay. In tales from Polynesia, Old Spider is the creator of the earth, moon, and sky. And in parts of West Africa and the West Indies, countless humorous tales are told about Anansi, the trickster spider who is forever trying to outwit the other animals, but often is the victim of his own pranks. At the same time, he also brings essential benefits to humankind, teaching men how to sow grain; instituting the division of day and night; creating the sun, moon, and stars; and being the origin of all stories.