The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (50 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

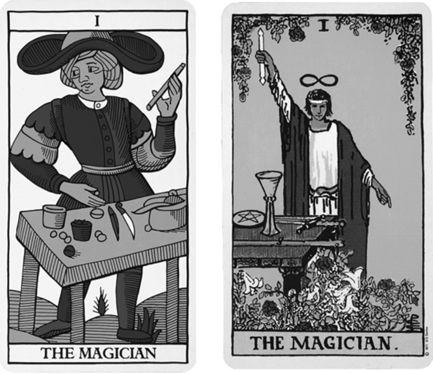

Two different ideas of the magic wand appear on these tarot cards. On the left, the street magician’s wand serves as symbol of his profession and a useful device for directing the attention of his audience. On the right, an authentic wizard uses his wand to call down the powers of the heavens for use on Earth

. (

photo credit 52.1

) (

photo credit 52.2

)

Some of the oldest magic wands still in existence today come from ancient Egypt and date back to 2800

B.C.

Carved primarily from hippopotamus ivory, they were believed to give the wizard who held them the powers of that formidable beast. Later wands, from around 2100

B.C.

, are curved and highly decorated with magical creatures such as the

griffin

and the

sphinx

, as well as

cats

, baboons, lions, bulls, turtles, panthers,

snakes

, frogs, crocodiles, and scarab beetles. These were known as “apotropaic” wands (meaning “something that turns away evil”) and were used to counter the power of

demons

. A long, thin, bronze wand in the shape of a cobra, discovered in a tomb in the ancient capital of Thebes, brings to mind the wands of Moses, Aaron, and Pharaoh’s wizards that, in a tale from the biblical book of Exodus, all turn into serpents.

In fiction, magic wands first appear in

The Odyssey

, written by the Greek poet Homer in about 800 or 900

B.C.

The beautiful witch

Circe

uses her wand to transform the hero’s crew of sailors into a herd of squealing pigs. Changing one thing into another is a classic literary use of the magic wand, depicted in countless fairy tales. The best-known example is the star-tipped wand used by Cinderella’s fairy godmother to transform mice into horses and a pumpkin into a coach. Other fabled wands belong to

Merlin

, wizard and mentor to King Arthur, and to the Greek god Hermes, who uses his wand (or

caduceus

) to make himself invisible to mortal men.

In early modern Europe, many practitioners of

magic

regarded the wand as an essential tool. It was used by ritual magicians (see

magic

) for casting spells, as well as drawing “magic circles” that would protect the magician from the harmful influence of any demons or spirits he planned to conjure up. Lacking the convenience of Diagon Alley shopping, aspiring magicians turned to spell books for instructions on how to design and manufacture a wand. According to

The Key of Solomon

, one of the most famous magic books of the Middle Ages, the ideal wand should be made of hazel and cut from a tree with a single blow of a newly made axe. Some authorities claimed that the potency of the wand could be kicked up a notch or two by adding magnetized tips to the ends, attaching crystals, or inscribing

magic words

or sacred names on the wand. As the wand was carved, the magician called upon the appropriate spirits, demons, or gods to endow the wand with its desired powers—to heal the sick, control the forces of nature, or grant the practitioner’s every wish.

While ritual magicians took their work very seriously, by the early fifteenth century wands were also being used for more lighthearted ends—as a standard prop of the street entertainers who performed “magic” as a livelihood. From the performer’s point of view, the wand served at least two important functions: It was the agent that apparently caused the magic to happen, and it helped fool the audience by directing their attention to one thing while the magician secretly did something else. Magic wands are, of course, a hallmark of stage magicians today. Several performers we know collect “trick wands” that collapse, bend, change color, shoot streamers, or break into pieces. This brings to mind those trick wands manufactured by the entrepreneurial Weasley twins, who seem to have used magic to make the same kind of gimmicked item a muggle might buy in a joke shop or conjuror’s supply store.

One of the snazziest of all wands is the winged and

snake

-entwined caduceus carried by Hermes, the Greek god of communication and master of magic and trickery. Given to him by his brother Apollo in exchange for a flute, the caduceus became Hermes’ badge of office.

The design of the caduceus—two serpents entwined around a central rod—can be found in Mesopotamian art dating back as early as 3500 B.C. Centuries later, the Greeks added wings to the rod to represent Hermes’ swiftness and placed an orb or globe on top. According to Roman legend, the caduceus was formed when Hermes (called Mercury by the Romans) came upon a pair of fighting serpents. He placed his wand between them, whereupon the snakes became friends and coiled themselves around the rod, and have been together ever since. In this version of the story, the wand represents harmony through communication. During the Middle Ages, alchemists like Nicholas Flamel believed that the snakes represented the union of opposites.

The caduceus is sometimes used as a symbol of the medical profession, although the true medical symbol is the staff of Asclepius, Greek god of medicine: a long staff entwined by a single serpent. The serpent entwining the staff is said to represent rejuvenation, because the snake sheds its old skin every year. Thus it symbolizes the physical rejuvenation that comes through medicine and healing.

Physicians during the Middle Ages traditionally carried a staff or cane as sign of their profession, and many attributed magical healing powers to the rod. Because of years of confusion between the caduceus and the staff of Asclepius, both wands are now associated with medicine, healing, and in some places, health insurance.

(

photo credit 52.3

)