The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (22 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

Although neighbours in areas with low levels of trust (see Chapter 4) may feel less inclined to intervene for the common good, they seem to be more pugnacious. In

Bowling Alone

, sociologist Robert Putnam linked a measure of aggression to levels of social capital in US states. In a survey, people were asked to say whether they agreed or disagreed with the sentence: ‘I’d do better than average in a fist fight.’ Putnam says citizens in states with low social capital are ‘readier for a fight (perhaps because they need to be), and they are predisposed to mayhem’.

25

, p. 310

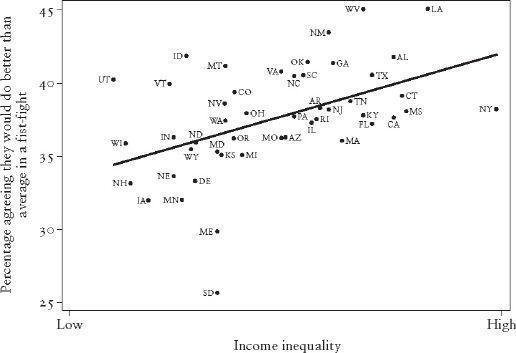

When we analyse this measure of pugnacity in relation to inequality within states, we find just as strong a relation as Putnam showed with social capital (Figure 10.5).

Figure 10.5

In less equal states more people think they would do better than average in a fist fight.

So violence is most often a response to disrespect, humiliation and loss of face, and is usually a male response to these triggers. Even within the most violent of societies, most people don’t react violently to these triggers because they have ways of achieving and maintaining their self-respect and sense of status in other ways. They might have more of the trappings of status – a good education, nice houses and cars, good jobs, new clothes. They may have family, friends and colleagues who esteem them, or qualifications they are proud of, or skills that are valued and valuable, or education that gives them status and hope for the future. As a result, although everybody experiences disrespect and humiliation at times, they don’t all become violent; we all experience loss of face but we don’t turn round and shoot somebody. In more unequal societies more people lack these protections and buffers. Shame and humiliation become more sensitive issues in more hierarchical societies: status becomes more important, status competition increases and more people are deprived of access to markers of status and social success. And if your source of pride is your immaculate lawn, you’re going to be more than a bit annoyed when that pride gets trampled on.

PEAKS AND TROUGHS

Homicide rates in America, after rising for decades, peaked in the early 1990s, then fell to their lowest level in the early 2000s. In 2005, they started to rise again.

226

Similarly, after peaking in the early 1990s, teenage pregnancy and birth rates began to fall in America, and the decline was particularly steep for African-Americans.

227

But in 2006, the teenage birth rate also started to rise again, and the biggest reversal was for African-American women.

228

Some people have tried to explain the decline in violence by pointing to changes in policing or drug use or access to guns, or even the ‘missing’ cohort of young men who were

not

born because of increased access to abortion. Explanations for the fall in teenage birth rates focused on changes in the number of teenagers who are sexually active and increasing contraceptive use. But what influences whether or not young people use drugs, buy guns, have sex or use contraception? Why are homicides and teenage births now rising again? And how do these trends match up with changes in inequality? Why have homicides and teenage births moved in parallel?

To examine this in more detail, we need data on recent short-term fluctuations in overall income inequality in the USA. The best data come from a collaborative team of researchers from the USA, China and the UK, who have produced a series of annual estimates.

229

These show inequality rising through the 1980s to a peak in the early 1990s. The following decade saw an overall decline in inequality, with an upturn since 2000. So there is a reasonable match between recent trends in homicides, teenage births and inequality – rising through the early 1990s and declining for a decade or so, with a very recent upturn.

Although violence and teenage births are complex issues and rates in each can respond to lots of other influences, the downward trends through the 1990s were consistent with improvements in the relative incomes of people at the very bottom of the income distribution. The distribution of income can be more stretched out over some parts of its range than others. A society may get more unequal because the poor are getting left further behind the middle, or because the rich are pulling further ahead. And who suffers from low social status may also vary from one society to another. Among societies with the same overall level of inequality, in one it may be the elderly who are most deprived relative to the rest of society, in another it may be ethnic minority groups.

From the early 1990s in America there was a particularly dramatic decline in relative poverty and unemployment for young people at the bottom of the social hierarchy. Although the rich continued to pull further away from the bulk of the population, from the early 1990s the

relative

position of the very poorest Americans began to improve.

230

–

231

As violence and teenage births are so closely connected to relative deprivation and concentrated in the poorest areas, it is what happens at the very bottom that matters most – hence the trends in violence and teenage births.

232

These trends, during the 1990s, contrast with what had been happening previously. The decades leading up to the 1990s saw a long sustained deterioration in opportunities and status for young people at the bottom of both American and British society. In the USA, from about 1970 through the early 1990s, the earning position of young men declined, and employment prospects for young people who dropped out of high school or who completed high school but didn’t go on to college worsened,

233

and violence and teenage births increased. In a recent study, demographer Cynthia Colen and her colleagues showed that falling levels of unemployment during the 1990s explained 85 per cent of the decline in rates of first births to 18–19-year-old African-Americans.

234

This was the group experiencing the biggest drop in teen births. Welfare reform and changes in the availability of abortion, in contrast, appeared to have had little impact.

In the UK, the impact of the economic recession and widening income differences during the 1980s can also be traced in the homicide rate. As health geographer Danny Dorling pointed out, with respect to these trends:

235

, pp. 36–7

There is no natural level of murder . . . For murder rates to rise in particular places . . . people have to be made to feel more worthless. Then there are more fights, more brawls, more scuffles, more bottles and more knifes and more young men die . . . These are the same young men who saw many of their counterparts, brought up in better circumstances and in different parts of Britain, gain good work, or university education, or both, and become richer than any similarly sized cohort of such young ages in British history.

In summary, we can see that the association between inequality and violence is strong and consistent; it’s been demonstrated in many different time periods and settings. Recent evidence of the close correlation between ups and downs in inequality and violence show that if inequality is lessened, levels of violence also decline. And the evolutionary importance of shame and humiliation provides a plausible explanation of why more unequal societies suffer more violence.

The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.

Fyodor Dostoevsky,

The House of the Dead

In the USA, prison populations have been increasing steadily since the early 1970s. In 1978 there were over 450,000 people in jail, by 2005 there were over 2 million: the numbers had quadrupled. In the UK, the numbers have doubled since 1990, climbing from around 46,000 to 80,000 in 2007. In fact, in February 2007, the UK’s jails were so full that the Home Secretary wrote to judges, asking them to send only the most serious criminals to prison.

This contrasts sharply with what has been happening in some other rich countries. Through the 1990s, the prison population was stable in Sweden and declined in Finland; it rose by only 8 per cent in Denmark, 9 per cent in Japan.

236

More recently, rates have been falling in Ireland, Austria, France and Germany.

237

CRIME OR PUNISHMENT?

The number of people locked up in prison is influenced by three things: the rate at which crimes are actually committed, the tendency to send convicted criminals to prison for particular crimes, and the lengths of prison sentences. Changes in any of these three can lead to changes in the proportion of the population in prison at any point in time. We’ve already described the tendency for violent crimes to be more common in more unequal societies in Chapter 10. What has been happening to crime rates in the USA and UK as rates of imprisonment have skyrocketed?

Criminologists Alfred Blumstein and Allen Beck have examined the growth in the US prison population.

238

Only 12 per cent of the growth in state prisoners between 1980 and 1996 could be put down to increases in criminal offending (dominated by a rise in drugrelated crime). The other 88 per cent of increased imprisonment was due to the increasing likelihood that convicted criminals were sent to prison rather than being given non-custodial sentences, and to the increased length of prison sentences. In federal prisons, longer prison sentences are the main reason for the rise in the number of prisoners. ‘Three-strikes’ laws, minimum mandatory sentences and ‘truth-in-sentencing’ laws (i.e., no remission) mean that some convicted criminals are receiving long sentences for minor crimes. In California in 2004, there were 360 people serving life sentences for shoplifting.

239

In the UK, prison numbers have also grown because of longer sentences and the increased use of custodial sentences for offences that a few years ago would have been punished with a fine or community sentence.

240

About forty prison sentences for shoplifting are handed out every day in the UK. Crime rates in the UK were falling as inexorably as imprisonment rates were rising.

The prison system in the Netherlands has been described by criminologist David Downes, professor emeritus of social administration at the London School of Economics.

241

He describes how two-thirds of the difference between the low rate of imprisonment in the Netherlands and the much higher rate in the UK is due to the different use of custodial sentences and the length of those sentences, rather than differences in rates of crime.

Comparing different countries, Marc Mauer of the Sentencing Project

242

shows that in the USA, people are sent to prison more often, and for longer, for property and drug crimes than they are in Canada, West Germany and England and Wales. For example, in the USA burglars received average sentences of sixteen months, whereas in Canada the average sentence was five months. And variations in crime rates didn’t explain more than a small amount of the variation in rates of imprisonment when researchers looked at Australia, New Zealand and a number of European countries. If crime rates can’t explain different rates of imprisonment, can inequality do better?