The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (20 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

In the world in which humans evolved, these different strategies make sense. If you can’t rely on your mate or other people, and you can’t rely on resources, then it may once have made sense to get started early and have lots of children – at least some will survive. But if you can trust your partner and family to be committed to you and to provide for you, it makes sense to have fewer children and to devote more attention and resources to each one.

Rachel Gold and colleagues found that the relationship between inequality and teenage birth rates in the USA might be acting through the impact of inequality on social capital, which we discussed in Chapter 4.

192

Among US states, that is, those with lower levels of social cohesion, civic engagement and mutual trust – exactly the conditions which might favour a quantity strategy – teenage birth rates are higher.

Several studies have also shown that early conflict and the absence of a father

do

predict earlier maturation – girls in such a situation become physically mature and start their periods earlier than girls who grow up without those sources of stress.

193

–

194

And reaching puberty earlier increases the likelihood of girls becoming sexually active at an early age and of teenage motherhood.

195

Father absence may be particularly important for teenage pregnancy. In a study of two large samples in the USA and New Zealand, psychologist Bruce Ellis and his colleagues followed girls from early childhood through to adulthood.

196

In both countries, the longer a father was absent from the family, the more likely it was that his daughter would have sex at a young age and become a teenage mother – and this strong effect could not be explained away by behavioural problems of the girls, by family stress, parenting style, socio-economic status, or by differences in the neighbourhoods in which the girls grew up. So there may be deep-seated adaptive processes which lead from more stressful and unequal societies – perhaps particularly from low social status – to higher teenage birth rates. Unfortunately, while we can obtain international data on single-parent households, being a single parent means very different things in different countries, and there are no international data that tell us how many fathers are absent from their children’s lives.

WHAT ABOUT THE DADS?

Throughout this chapter, we’ve been discussing the problem of teenage parenting exclusively in terms of teenage mothers, but what about the fathers? Let’s return to the story of the three sisters. The father of the 12-year-old girl’s baby left her shortly after his son was born. The boy named by the middle sister as the father of her little girl denied having sex with her and demanded a paternity test. And the 38-year-old father of the oldest sister’s baby already had at least four other children.

Sociologists Graham and McDermott discuss what has been learned from studies where researchers talk at length to young women about their experiences. What they show is that these sisters’ experiences with their babies’ fathers are typical.

190

Motherhood is a way in which young women in deprived circumstances join adult social networks – networks which usually include their own mothers and other relatives, and these supportive networks help them transcend the social stigma of being a teenage mother. According to Graham and McDermott, young women prioritize their relationships with the babies, over their often difficult relationships with the babies’ fathers, because they feel this relationship is a ‘more certain source of intimacy than the heterosexual relationships they had . . . experienced’.

Young men living in areas of high unemployment and low wages often can’t offer much in the way of stability or support. In communities with high levels of teenage motherhood, young men are themselves trying to cope with the many difficulties that inequality inflicts on their lives, and young fatherhood adds to those stresses.

Where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails and where any one class is made to feel that society is in an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob and degrade them, neither persons nor property will be safe.

Frederick Douglas, Speech on the 24th anniversary

of emancipation, Washington, DC, 1886

As we began to write this chapter, violence was in the headlines on both sides of the Atlantic. In the USA, an 18-year-old man with a shotgun entered a shopping mall in Salt Lake City, Utah, killing five people and wounding four others, apparently at random, before being shot dead by police. In the UK, there was a wave of killings in South London, including the murder of three teenage boys in less than a fortnight. But perhaps the story that best illustrates what this chapter is about occurred in March 2006, in a quiet suburb of Cincinnati, Ohio. Charles Martin, a 66-year-old, telephoned the emergency services.

197

‘I just killed a kid,’ he told the operator, ‘I shot him with a goddamn 410 shotgun twice.’ Mr Martin had shot his 15-year-old neighbour. The boy’s crime? He had run across Mr Martin’s lawn. ‘Kid’s just been giving me a bunch of shit, making the other kids harass me and my place.’

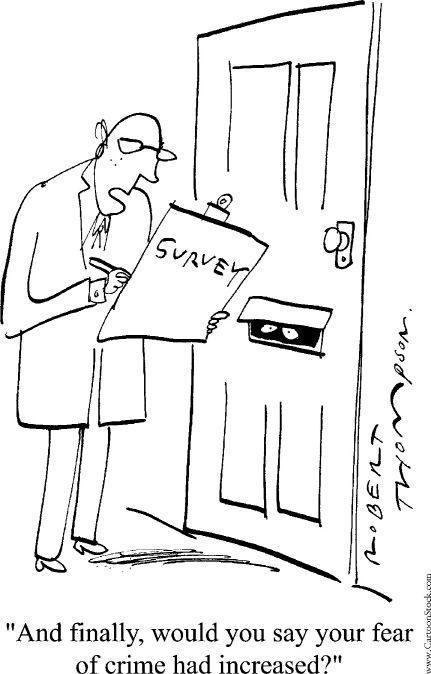

Violence is a real worry in many people’s lives. In the most recent British Crime Surveys, 35 per cent of people said they were very worried or fairly worried about being a victim of mugging, 33 per cent worried about physical attack, 24 per cent worried about rape,

and 13 per cent worried about racially motivated violence. More than a quarter of the people who responded said they were worried about being insulted or pestered in public.

198

Surveys in America and Australia report similar findings – in fact fear of crime and violence may be as big a problem as the actual level of violence. Very few people are victims of violent crime, but fear of violence affects the quality of life of many more. Fear of violence disproportionately affects the vulnerable – the poor, women and minority groups.

199

In many places, women feel nervous going out at night or coming home late; old people double-lock their doors and won’t open them to strangers. These are important infringements of basic human freedoms.

People’s fears of crime, violence and anti-social behaviour don’t always match up with rates and trends in crime and violence. A recent down-swing in homicide rates in America (which has now ended), was not matched by a reduction in people’s fear of violence. We will return to recent trends later. First, let’s turn our attention to differences in rates of actual violence between different societies and look at some of the similarities and the differences between them.

In some ways patterns of violence are remarkably consistent across time and space. In different places and at different times, violent acts are overwhelmingly perpetrated by men, and most of those men are in their teens or early twenties. In her book,

The Ant and the Peacock

, philosopher and evolutionary psychologist Helena Cronin shows how closely correlated the age and sex characteristics of murderers are in different places.

200

We reproduce her graph showing murder rates, comparing Chicago with England and Wales (Figure 10.1). The age of the perpetrator is shown along the bottom; up the side is the murder rate, and there are separate lines for men and women. It is immediately apparent that murder rates peak in the late teens and early twenties for men, and that rates for women are much lower at all ages. The age and sex distribution is astonishingly similar both in Chicago and in England and Wales. However, what is less obvious is that the scales on the left- and right-hand sides of the graph are very different. On the left-hand side of the graph, the scale shows homicide rates per million people in England and

Figure 10.1

Homicides by age and sex of perpetrator. England and Wales compared with Chicago.

200

Wales, going from zero to 30. On the right-hand side, the scale shows homicide rates in Chicago, and here the scale runs from zero to 900 murders per million. Despite the striking similarities in the patterns of age and sex distribution, there is something fundamentally different in these places; the city of Chicago had a murder rate 30 times higher than the rate in England and Wales. On top of the biological similarities there are huge environmental differences.

Violent crimes are almost unknown in some societies. In the USA, a child is killed by a gun every three hours. Despite having a much lower rate than the USA, the UK is a violent society, compared to many other countries: over a million violent crimes were recorded in 2005–2006. And within any society, while it is generally young men who are violent, most young men are not. Just as it is the discouraged and disadvantaged among young women who become teenage mothers, it is poor young men from disadvantaged neighbourhoods who are most likely to be both victims and perpetrators of violence. Why?

‘IF YOU AIN’T GOT PRIDE, YOU GOT NOTHING.’

201

, p. 29

James Gilligan is a psychiatrist at Harvard Medical School, where he directs the Center for the Study of Violence, and has worked on violence prevention for more than thirty years. He was in charge of mental health services for the Massachusetts prison system for many years, and for most of his years as a clinical psychiatrist he worked with the most violent of offenders in prisons and prison mental hospitals. In his books,

Violence

202 and

Preventing Violence

,

201

he argues that acts of violence are ‘attempts to ward off or eliminate the feeling of shame and humiliation – a feeling that is painful, and can even be intolerable and overwhelming – and replace it with its opposite, the feeling of pride’. Time after time, when talking to men who had committed violent offences, he discovered that the triggers to violence had involved threats – or perceived threats – to pride, acts that instigated feelings of humiliation or shame. Sometimes the incidents that led to violence seemed incredibly trivial, but they all evoked shame. A young neighbour walking disrespectfully across your immaculate lawn . . . the popular kids in the school harassing you and calling you a faggot . . . being fired from your job . . . your woman leaving you for another man . . . someone looking at you ‘funny’ . . .

Gilligan goes so far as to say that he has ‘yet to see a serious act of violence that was not provoked by the experience of feeling shamed and humiliated . . . and that did not represent the attempt to . . . undo this “loss of face”’.

202

, p. 110

And we can all recognize these feelings, even if we would never go so far as to act on them. We recognize the stomach-clenching feelings of shame and embarrassment, the mortification that we feel burning us up when we make ourselves look foolish in the eyes of others. We know how important it is to feel liked, respected, and valued.

203

But if all of us feel these things, why is it predominantly among young men that those feelings escalate into violent acts?

Here the work of evolutionary psychologists Margo Wilson and Martin Daly helps to make sense of these patterns of violence. In their 1988 book

Homicide

204

and a wealth of books, chapters and articles since, they use statistical, anthropological and historical data to show how young men have strong incentives to achieve and maintain as high a social status as they can – because their success in sexual competition depends on status.

77

,

205

–

208

While looks and physical attractiveness are more important for women, it is status that matters most for sexual success among men. Psychologist David Buss found that women value the financial status of prospective partners roughly twice as much as men do.

209

So while women try to enhance their sexual attractiveness with clothes and make-up, men compete for status. This explains not only why feeling put down, disrespected and humiliated are the most common trigger for violence; it also explains why most violence is between men – men have more to win or lose from having (or failing to gain) status. Reckless, even violent behaviour comes from young men at the bottom of society, deprived of all the markers of status, who must struggle to maintain face and what little status they have, often reacting explosively when it is threatened.