The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (15 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

But this is not what happens. During the epidemiological transition, which we discussed in Chapters 1 and 6, in which chronic diseases replaced infectious diseases as the leading causes of death, obesity changed its social distribution. In the past the rich were fat and the poor were thin, but in developed countries these patterns are now reversed.

106

The World Health Organization set up a study in the 1980s to monitor trends in cardiovascular diseases, and the risk factors for these diseases, including obesity, in twenty-six countries. It found that, as rates of obesity have increased, their social gradient has steepened.

107

By the early 1990s obesity was more common among poorer women, compared to richer women, in all twenty-six countries, and among poorer men in all except five. As journalist Polly Toynbee declared in a newspaper article in 2004: ‘Fat is a class issue.’

108

Pointing to the high rates of obesity in the USA and the low rates among the Scandinavian countries, which prove that we don’t find high levels of obesity in all modern, rich societies, she suggested that income inequality might contribute to the obesity epidemic.

INCOME INEQUALITY AND OBESITY

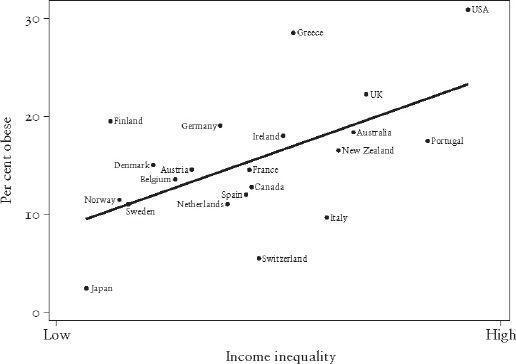

Figure 7.1 shows that levels of obesity tend to be lower in countries where income differences are smaller. The data on obesity come from the International Obesity Task Force and show the proportion of the adult population, both men and women, who are obese – a Body Mass Index (BMI) of more than 30.

109

The differences between countries are large. In the USA, just over 30 per cent of adults are obese; a level more than twelve times higher than Japan, where only 2.4 per cent of adults are obese. Because these figures are for BMI, not just weight, they’re not due to differences in average height.

Figure 7.1

More adults are obese in more unequal countries.

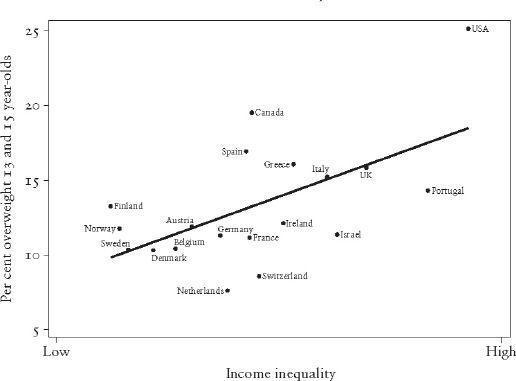

The same pattern can be seen internationally for children (Figure 7.2). Our figures on the percentage of young people aged 13 and 15 who are overweight, reported in the 2007 UNICEF report on child wellbeing, came originally from the World Health Organization’s Health Behaviour in School-age Children survey.

110

There are no data for Australia, New Zealand or Japan from this survey, but the relationship with inequality is still strong enough to be sure it is not due to chance. The differences between countries are smaller for overweight children than for adult obesity. In the country with the lowest level, the Netherlands, 7.6 per cent of children aged 13 and 15 are overweight, which is one-third the rate in the USA, where 25.1 per cent are overweight. (As these figures are based on children reporting their height and weight, rather than being measured, the true prevalence of overweight is probably higher in all countries, but that shouldn’t make much difference to how they are related to inequality.)

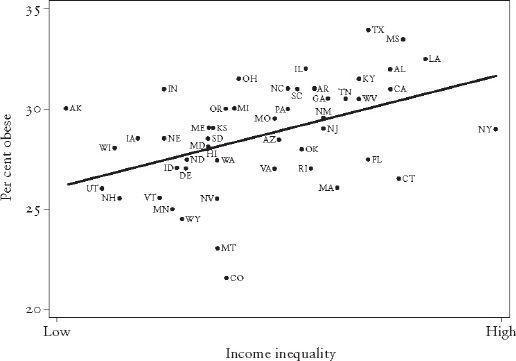

Within the USA, there are no states with levels of adult obesity lower than 20 per cent. Colorado has the lowest obesity prevalence, at 21.5 per cent, compared to 34 per cent in Texas, which has the highest.

*

But the relationship with inequality is still strong enough for us to be confident it isn’t due to chance. Other researchers have found similar relationships. One study found that higher state-income inequality was associated with abdominal weight gain in men,

111

others have found that income inequality increases the risk of inactive lifestyles.

112

Overweight among the poor seems to be particularly strongly associated with income inequality.

Figure 7.2

More children are overweight in more unequal countries.

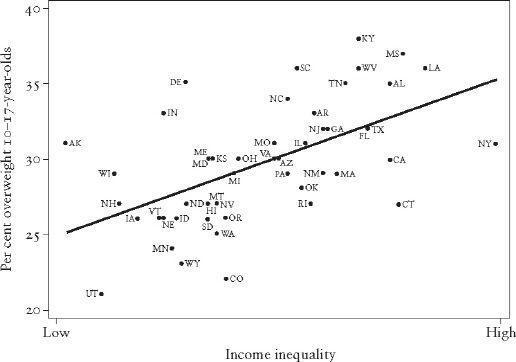

For children in the USA, we obtained data from the National Survey of Children’s Health (Figure 7.4). Just as for the international figures for children, these data are for overweight (rather than obese) children, aged 10–17 years. (The child’s height and weight are reported by the parent, or the adult who knows the child best.) The relationship with inequality is even stronger for children than for adults.

Figure 7.3

More adults are obese in more unequal US states.

113

Figure 7.4

More children are overweight in more unequal US states.

EATING FOR COMFORT . . .

The pathways linking income inequality to obesity are likely to include calorie intake and physical activity. Indeed, our own research has shown that per capita calorie intake is higher in more unequal countries. This explained part of the relationship between inequality and obesity, but less for women than for men.

114

Other researchers have shown that income inequality in US states is related to physical inactivity.

112

It seems that people in more unequal societies are eating more and exercising less. But in studies in Australia, the UK and Sweden the amount that people eat, and the amount of exercise they do, fails to fully account for social class differences in weight gain and obesity.

115

–

118

Calorie intake and exercise are only part of the story. People with a long history of stress seem to respond to food in different ways from people who are not stressed. Their bodies respond by depositing fat particularly round the middle, in the abdomen, rather than lower down on hips and thighs.

119

–

120

As we saw in Chapter 6, chronic stress affects the action of the hormone cortisol, and researchers have found differences in cortisol and psychological vulnerability to stress tests among men and women with high levels of abdominal fat. People who accumulate fat around the middle are at particularly high risk of obesity-associated illnesses.

The body’s stress reaction causes another problem. Not only does it make us put on weight in the worst places, it can also increase our food intake and change our food choices, a pattern known as stress-eating or eating for comfort. In experiments with rats, when the animals are stressed they eat more sugar and fat. People who are chronically stressed tend either to over-eat and gain weight, or under-eat and lose weight. In a study in Finland, people whose eating was driven by stress ate sausages, hamburgers, pizza and chocolate, and drank more alcohol than other people.

121

Scientists are starting to understand how comfort eating may be a way we cope with particular changes in our physiology when we are chronically stressed, changes that go with feelings of anxiety.

122

The three obese children featured in the

Sun

newspaper, whom we described earlier, all seemed to have turned to comfort eating to deal with family break-ups. The nine-year-old girl said, ‘Chocolate is the only thing I’m interested in. It’s the only thing I live for . . . when I’m sad and worried I just eat.’ Her older brother gained 210 pounds (15 stone) in five years, after his parents divorced.

A number of years ago, the

Wall Street Journal

ran a series, ‘Deadly Diet’, on the nutrition problems of America’s inner cities.

123

Among the overweight people they interviewed was a 13-year-old girl living in a violent housing project (estate), who said that food and TV were a way of calming her nerves. An unemployed woman who knew that her diet and drinking were damaging her liver and arteries, still figured she ‘might as well live high on the hog’ while she could. A grandmother bringing up her grandchildren because of her daughter’s addiction to crack cocaine, said:

Before I was so upset that my daughter was on this crack I couldn’t eat. I turned to Pepsi – it was like a drug for me. I couldn’t function without it. I used to wake up with a Pepsi in my hand. A three-liter bottle would just see me through the day.

Recent research suggests that food stimulates the brains of chronic over-eaters in just the same ways that drugs stimulate the brains of addicts.

124

–

126

Studies using brain scans have shown that obese people respond both to food and to feeling full differently from thin people.

127

. . . EATING (OR NOT) FOR STATUS

But food choices and diets aren’t just dictated by the way we feel – they’re also patterned by social factors. We make food choices for complicated cultural reasons – sometimes we like foods we grew up eating, which represent home to us, sometimes we want foods that represent a lifestyle we’re trying to achieve. We offer food to other people to show that we love them, or to show that we’re sophisticated, or that we can afford to be generous. Food has probably always played this role; it’s the necessary component of the feast, with all of its social meanings. But now, with the easy availability of cheap, energy-dense foods, whatever social benefits might come from frequent feasting, they are, so to speak, outweighed by the drawbacks.

In the

Wall Street Journal

’s ‘Deadly Diet’ series, a recent immigrant from Puerto Rico describes how her family used to live on an unchanging diet of rice, beans, vegetables, pork and dried fish. Since moving to Chicago, they have enjoyed fizzy drinks, pizza, hamburgers, sugared breakfast cereals, hotdogs and ice-cream. ‘I can’t afford to buy the children expensive shoes or dresses . . . but food is easier so I let them eat whatever they want.’ Most of all, the family enjoy going to fast-food restaurants and eat out twice a month, although the children would like to go more often. ‘We feel good when we go to those places . . . we feel like we’re Americans, that we’re here and we belong here.’