The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (13 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

Social support and social networks have also been linked both to the incidence of cardiovascular disease and to recovery from heart attacks. In a striking experiment, researchers have also shown that people with friends are less likely to catch a cold when given the same measured exposure to the cold virus – in fact the more friends they had, the more resistant they were.

72

Experiments have also shown that physical wounds heal faster if people have good relationships with their intimate partners.

73

Social status and social integration are now well established as important determinants of population health and, increasingly, researchers are also recognizing that stress in early life, in the womb as well as in infancy and early childhood, has an important influence on people’s health throughout their lives.

74

–

75

Stress in early life affects physical growth, emotional, social and cognitive development, as well as later health and health behaviours. And the socioeconomic status of the families in which children live also determines their lifelong trajectories of health and development.

76

Taken together, social status, social networks and stress in early childhood are what researchers label ‘psychosocial factors’, and these are of increasing importance in the rich, developed countries where material living standards, as we described in Chapter 1, are now high enough to have ceased to be important direct determinants of population health.

LIFE IS SHORT WHERE LIFE IS BRUTAL

Evolutionary psychologists Margo Wilson and Martin Daly were interested in whether adopting more impulsive and risky strategies was an evolved response to more stressful circumstances in which life is likely to be shorter. In more threatening circumstances, then, more reckless strategies are perhaps necessary to gain status, maximize sexual opportunities, and enjoy at least some short-term gratifications. Perhaps only in more relaxed conditions, in which a longer life is assured, can people afford to plan for a long-term future.

77

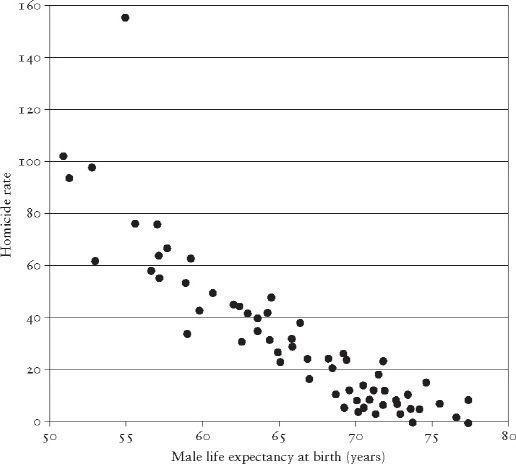

To test this hypothesis, they collected data on the murder rates for the seventy-seven community areas of Chicago, and then they collected data on death rates for those same areas, subtracting all of the deaths caused by homicide. When they put the two together, they showed a remarkably close relationship, seen in Figure 6.1 – neighbourhoods with high homicide rates were also neighbourhoods where people were dying younger from other causes as well. Something about these neighbourhoods seemed to be affecting both health and violence.

In Chapter 4 we showed how different developed countries and

Figure 6.1

Homicide rates are related to male life expectancy in seventy-seven neighbourhoods in Chicago. (Calculation of life expectancy included deaths from all causes

except

homicide.)

77

US states vary in the levels of social trust that people feel. There are sixfold differences in levels of trust between developed countries and fourfold differences among US states. We mentioned that levels of trust have been linked to population health and, in fact, research on social cohesion and social capital has mushroomed over the past ten years or so. More than forty papers on the links between health and social capital have now been published.

78

In the United States, epidemiologist Ichiro Kawachi and his colleagues at the Harvard School of Public Health looked at death rates in thirty-nine states in which the General Social Surveys had been conducted in the late 1980s.

79

These surveys allowed them to count how many people in each state were members of voluntary organizations, such as church groups and unions. This measure of group membership turned out to be a strong predictor of deaths from all causes combined, as well as deaths from coronary heart disease, cancers, and infant deaths. The higher the group membership, the lower the death rate.

Robert Putnam looked at social capital in relation to an index of health and health care for the US states.

25

This index included information on such things as the percentage of babies born with low birthweight, the percentage of mothers receiving antenatal care, many different death rates, expenditure on health care, the number of people with AIDS and cancer, immunization rates, use of car safety belts, and numbers of hospital beds, among other factors. The health index was closely linked to social capital; states such as Minnesota and Vermont had high levels of social capital and scored high on the health index, states such as Louisiana and Nevada scored badly on both. Clearly, it’s not just our individual social status that matters for health, the social connections between us matter too.

HEALTH AND WEALTH

Let’s consider the health of two babies born into two different societies.

Baby A is born in one of the richest countries in the world, the USA, home to more than half of the world’s billionaires. It is a country that spends somewhere between 40–50 per cent of the world’s total spending on health care, although it contains less than 5 per cent of the world’s population. Spending on drug treatments and high-tech scanning equipment is particularly high. Doctors in this country earn almost twice as much as doctors elsewhere and medical care is often described as the best in the world.

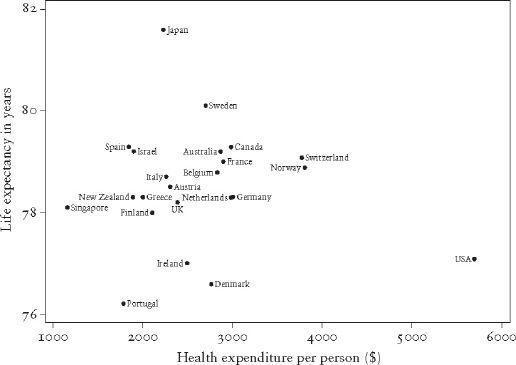

Baby B is born in one of the poorer of the western democracies, Greece, where average income is not much more than half that of the USA. Whereas America spends about $6,000 per person per year on health care, Greece spends less than $3,000. This is in real terms, after taking into account the different costs of medical care. And Greece has six times fewer high-tech scanners per person than the USA.

Surely Baby B’s chances of a long and healthy life are worse than Baby A’s?

In fact, Baby A, born in the USA, has a life expectancy of 1.2 years less than Baby B, born in Greece. And Baby A has a 40 per cent higher risk of dying in the first year after birth than Baby B. Among developed countries, there are even bigger contrasts than the comparison we’ve used here: babies born in the USA are twice as likely to die in their first year than babies in Japan, and the difference in average life expectancy between the USA and Sweden is three years, between Portugal and Japan it is over five years. Some comparisons are even more shocking: in 1990, Colin McCord and Harold Freeman in the Department of Surgery at Columbia University calculated that black men in Harlem were less likely to reach the age of 65 than men in Bangladesh.

80

Among other things, our comparison between Baby A and Baby B shows that spending on health care and the availability of high-tech medical care are not related to population health. Figure 6.2 shows that, in rich countries, there is no relationship between the amount of health spending per person and life expectancy.

Figure 6.2

Life expectancy is unrelated to spending on health care in rich countries (currencies converted to reflect purchasing power).

THE ‘BIG IDEA’

If average levels of income don’t matter, and spending on high-tech health care doesn’t matter, what does? There are now a large number of studies of income inequality and health that compare countries, American states, or other large regions, and the majority of these studies show that more egalitarian societies tend to be healthier.

10

This vast literature was given impetus by a study by one of us, on inequality and death rates, published in the

British Medical Journal

in 1992.

81

In 1996, the editors of that journal, commenting on further studies confirming the link between income inequality and health, wrote:

The big idea is that what matters in determining mortality and health in a society is less the overall wealth of that society and more how evenly wealth is distributed. The more equally wealth is distributed the better the health of that society.

82

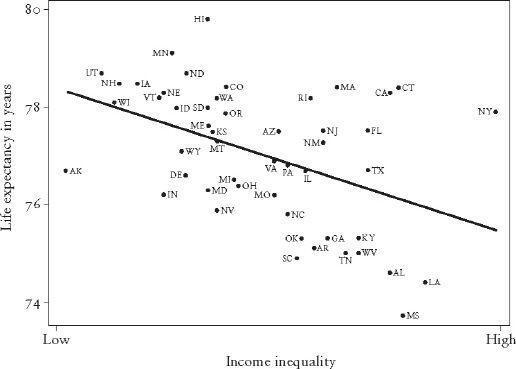

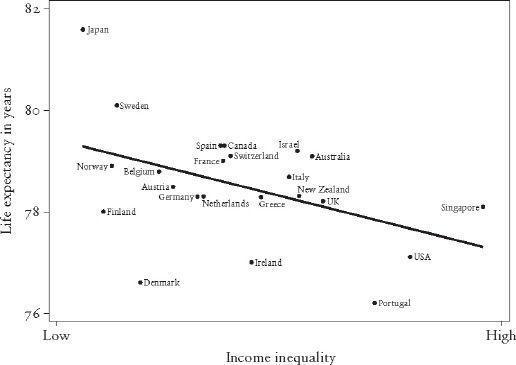

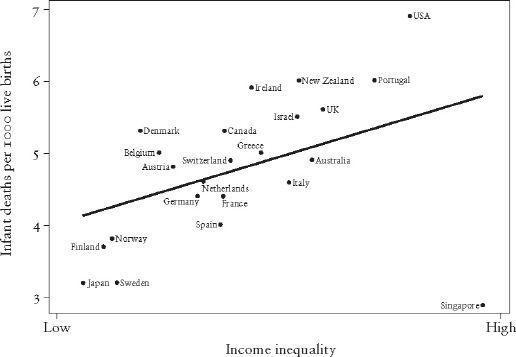

Inequality is associated with lower life expectancy, higher rates of infant mortality, shorter height, poor self-reported health, low birthweight, AIDS and depression. Figures 6.3–6.6 show income inequality in relation to life expectancy for men and women, and to infant mortality – first for the rich countries, and then for the US states.

Of course, population averages hide the differences in health

within

any population, and these can be even more dramatic than the differences

between

countries. In the UK, health disparities have been a major item on the public health agenda for over twenty-five years, and the current

National Health Service Plan

states that ‘No injustice is greater than the inequalities in health which scar our nation.

’

83

In the late 1990s the difference in life expectancy between the lowest and highest social class groups was 7.3 years for men and

Figure 6.3

Life expectancy is related to inequality in rich countries.

Figure 6.4

Infant mortality is related to inequality in rich countries.