The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (14 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

Figure 6.5

Life expectancy is related to inequality in US states.

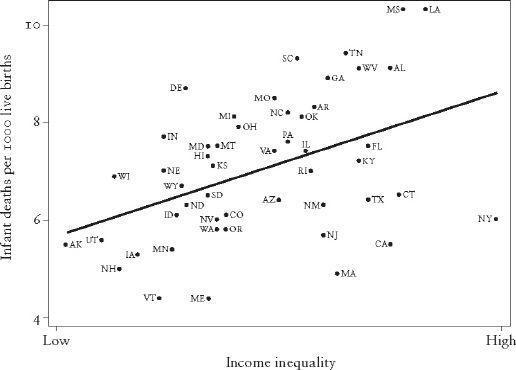

Figure 6.6

Infant mortality is related to inequality in US states.

7 years for women.

84

Studies in the USA often report even larger differences, such as a 28-year difference in life expectancy at age 16 between blacks and whites living in some of the poorest and some of the richest areas.

85

–

87

To have many years’ less life because you’re working-class rather than professional – no one can argue about the serious injustice that these numbers represent. Note that, as the Whitehall study showed, these gaps cannot be explained away by worse health behaviours among those lower down the social scale.

88

–

90

What, then, if the cost of that injustice is a three- or four-year shortening of

average

life expectancy if we live in a more unequal society?

We examined several different causes of death to see which had the biggest class differences in health. We found that deaths among working-age adults, deaths from heart disease, and deaths from homicide had the biggest class differences. In contrast, death rates from prostate cancer had small class differences and breast cancer death rates were completely unrelated to social class. Then we looked at how those different death rates were affected by income inequality, and found that those with big class differences were much more sensitive to inequality.

8

We also found that living in a more equal place benefited everybody, not just the poor. It’s worth repeating that health disparities are not simply a contrast between the ill-health of the poor and the better health of everybody else. Instead, they run right across society so that even the reasonably well-off have shorter lives than the very rich. Likewise, the benefits of greater equality spread right across society, improving health for everyone – not just those at the bottom. In other words, at almost any level of income, it’s better to live in a more equal place.

A dramatic example of how reductions in inequality can lead to rapid improvements in health is the experience of Britain during the two world wars.

91

Increases in life expectancy for civilians during the war decades were twice those seen throughout the rest of the twentieth century. In the decades which contain the world wars, life expectancy increased between 6 and 7 years for men and women, whereas in the decades before, between and after, life expectancy increased by between 1 and 4 years. Although the nation’s nutritional status improved with rationing in the Second World War, this was not true for the First World War, and material living standards declined during both wars. However, both wartimes were characterized by full employment and considerably narrower income differences – the result of deliberate government policies to promote co-operation with the war effort. During the Second World War, for example, working-class incomes rose by 9 per cent, while incomes of the middle class fell by 7 per cent; rates of relative poverty were halved. The resulting sense of camaraderie and social cohesion not only led to better health – crime rates also fell.

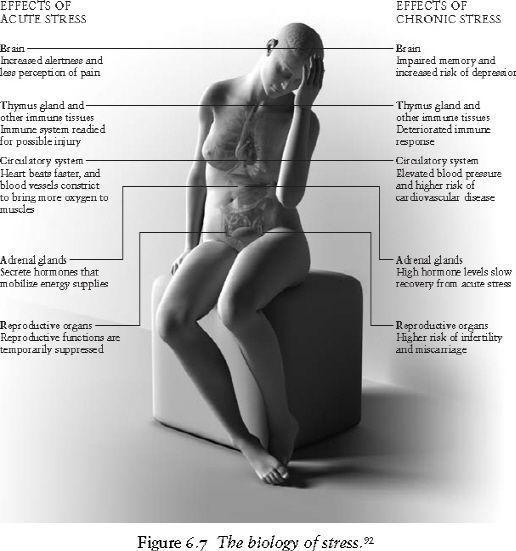

UNDER OUR SKIN

So how

do

the stresses of adverse experiences in early life, of low social status and lack of social support make us unwell?

92

The belief that the mind affects the body has been around since ancient times, and modern research has enhanced our understanding of the ways in which stress increases the risk of ill-health, and pleasure and happiness promote wellbeing. The psyche affects the neural system and in turn the immune system – when we’re stressed or depressed or feeling hostile, we are far more likely to develop a host of bodily ills, including heart disease, infections and more rapid ageing.

93

Stress disrupts our body’s balance, interferes with what biologists call ‘homeostasis’ – the state we’re in when everything is running smoothly and all our physiological processes are normal.

When we experience some kind of acute stress and experience something traumatic, our bodies go into the fight-or-flight response.

93

Energy stores are released, our blood vessels constrict, clotting factors are released into the bloodstream, anticipating injury, and the heart and lungs work harder. Our senses and memory are enhanced and our immune system perks up. We are primed and ready to fight or run away from whatever has caused the stress. If the emergency is over in a few minutes, this amazing response is healthy and protective, but when we go on worrying for weeks or months and stress becomes chronic, then our bodies are in a constant state of anticipation of some challenge or threat, and all those fight-or-flight responses become damaging.

The human body is superb at responding to the acute stress of a physical challenge, such as chasing down prey or escaping a predator. The circulatory, nervous and immune systems are mobilized while the digestive and reproductive processes are suppressed. If the stress becomes chronic, though, the continual repetition of theses responses can cause major damage.

Chronic mobilization of energy in the form of glucose into the bloodstream can lead us to put on weight in the wrong places (central obesity) and even to diabetes; chronic constriction of blood vessels and raised levels of blood-clotting factors can lead to hypertension and heart disease. While acute momentary stress perks up our immune system, chronic continuing stress suppresses immunity and can lead to growth failure in children, ovulation failure in women, erectile dysfunction in men and digestive problems for all of us. Neurons in some areas of the brain are damaged and cognitive function declines. We have trouble sleeping. Chronic stress wears us down and wears us out.

In this chapter we’ve shown that there is a strong relationship between inequality and many different health outcomes, with a consistent picture in the USA and developed countries. Our belief that this is a causal relationship is enhanced by the coherent picture that emerges from research on the psychosocial determinants of health, and the social gradients in health in developed countries. Position in society matters, for health and alternative explanations, such as higher rates of smoking among the poor, don’t account for these gradients. There are now a number of studies showing that income inequality affects health, even after adjusting for people’s individual incomes.

94

The dramatic changes in income differences in Britain during the two world wars were followed by rapid improvements in life expectancy. Similarly, in Japan, the influence of the post-Second World War Allied occupation on demilitarization, democracy and redistribution of wealth and power led to an egalitarian economy and unrivalled improvements in population health.

95

In contrast, Russia has experienced dramatic decreases in life expectancy since the early 1990s, as it moved from a centrally planned to a market economy, accompanied by a rapid rise in income inequality.

96

The biology of chronic stress is a plausible pathway which helps us to understand why unequal societies are almost always unhealthy societies.

Obesity: wider income gaps, wider waists

Food is the most primitive form of comfort

Sheila Graham

Obesity is increasing rapidly throughout the developed world. In some countries rates have doubled in just a few years. Obesity is measured by Body Mass Index (BMI)

*

to take height into account and avoid labelling people as overweight just because they are tall. The World Health Organization has set standards for using BMI to classify people as underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9), overweight (BMI 25–29.9) and obese (BMI >30). In the USA, in the late 1970s, close to half the population were overweight and 15 per cent were obese; now three-quarters of the population are overweight, and close to a third are obese. In the UK in 1980, about 40 per cent of the population were overweight and less than 10 per cent were obese; now two-thirds of adults are overweight and more than a fifth are obese.

97

–

100

This is a major health crisis, because obesity is so bad for health – it increases the risk of hypertension, type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, gallbladder disease and some cancers. Trends in childhood obesity are now so serious that they are widely expected to lead to shorter life expectancies for today’s children. That would be the first reversal in life expectancy in many developed countries since governments started keeping track in the nineteenth century.

101

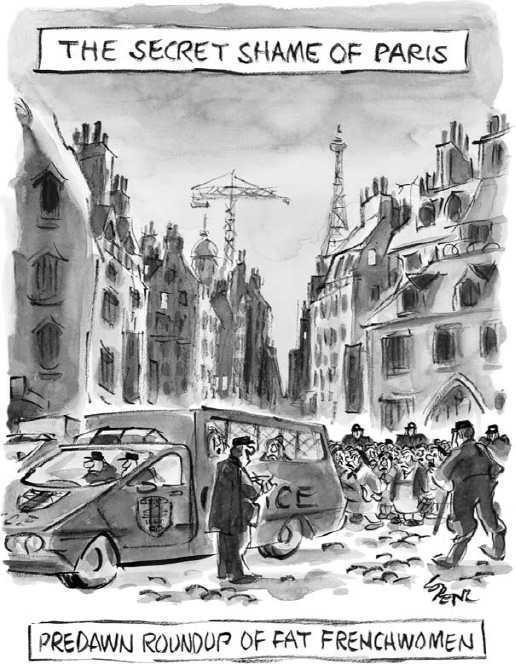

Apart from the health consequences, obesity reduces emotional and social wellbeing: overweight and obese adults and children suffer terribly. A 17-year-old from Illinois, weighing 409 lb (29 stone) described her physical pain: ‘my heart aches in my chest and I have arm pains and stuff and it gets scary’.

102

But just as hurtful are the memories she has of other children calling her names at school, her restricted social life and her feeling that her body is ‘almost a prison to me’.

Britain’s tabloid newspaper, the

Sun

, featured three obese children in the spring of 2007.

103

–

105

The youngest, a boy aged 8, weighed 218 lb (15.5 stone) and was being bullied at school – when he attended. His weight was so great that he often missed school due to his difficulties in walking there and back, and was exempt from wearing school uniform because none was available to fit him. His elder sister, aged 9, weighed 196 lb (14 stone) and was also being bullied and teased, by both children and adults. She said she found it ‘hard to breathe sometimes’, and did not like ‘having to wear ugly clothes’ and being unable to fit on the rides at amusement parks. Heaviest was the oldest boy who, at the age of 12, weighed 280 lbs (20 stone). He was desperately unhappy – expelled from two schools and suspended from a third, for lashing out at children who called him names.

THE ‘OBESOGENIC’ ENVIRONMENT

Many people believe that obesity is genetically determined, and genes do undoubtedly play a role in how susceptible different individuals are to becoming overweight. But the sudden rapid increase in obesity in many societies cannot be explained by genetic factors. The obesity epidemic is caused by changes in how we live. People often point to the changes in cost, ease of preparation and availability of energy-dense foods, to the spread of fast-food restaurants, the development of the microwave, and the decline in cooking skills. Others point to the decline in physical activity, both at work and in leisure time, increasing car use and the reduction in physical education programmes in schools. Modern life, it seems, conspires to make us fat. If there was no more to it than that, then we might expect to see more obesity among richer people, who are able to buy more food, more cars, etc., and high levels of obesity in all wealthy societies.