The Story of My Father (12 page)

I did go up to New Hampshire once by myself on a beautiful day late in the fall. I think I literally couldn’t believe it was as bad as I remembered it; or, rather, that my disbelief had been powerful enough to actually alter my memory of it. What I imagined, driving up, was that I’d clean the kitchen or one or two of the bedrooms where only a limited number of cats had been allowed. (One room, for instance, was for sick cats, another for “bad” cats, Bill had told us—by which I assume he meant murderous.)

When I opened the door, though, I felt the shock of appalled discovery all over again. It was unspeakable. And this time around, the flea population, deprived of its source of food, the cats, found me almost instantly. I felt them on my exposed flesh—their light touch, their bite. I ran outside, swatting and flailing. And then I was aware of them moving on my legs, under my overalls. In a panic I unlaced my shoes and kicked them off, then pulled my overalls down. A roiling black anklet was moving up each leg. Careless of cars going by in the road, I danced around in the overgrown grass in my underpants for a while, raking at my flesh, slapping myself. Finally I got dressed again, locked up the house, got in the car, and started the three-hour trip back down to Boston.

The next June, in the weeks before Ben went off to camp, I ran a kind of alternative camp for him and three friends—Jessica and Kate, whom he’d known since day-care days, and Nikko, an older friend of Kate’s who’d just graduated from high school and who was our salvation. He understood the notion of physical labor in a way the other three didn’t, they were so young. Weekdays they worked all day each day, though the three younger teenagers could sometimes be heard in the far reaches of the house shrieking and chasing each other around. The syringes in particular they found ghoulishly delightful, but we also discovered trunks full of jewelry and clothing from the thirties and forties that they made piles of to salvage. We used hoes, ice chippers, and shovels to pry up the dried, hardened shit. The cats had knocked many books off the shelves into the mess, and these had been covered over the years: the kids elaborated a fantasy about these new building materials: books and shit, like bricks and mortar, only stinkier.

My father had arranged to pay several hundred dollars a trip for the town garbage truck, and when we had enough barrels full of junk, when we’d piled the dried, hardened shit head-high in the living room once again, we’d call the collector to come and then run back and forth with the barrels, filling the truck with a combination of ruined furniture and fabrics and trash and barrel after barrel of shit and shit and more shit.

I cooked two enormous meals a day and packed lunches for all of them. In the afternoons when we were done working, we swam in the lake near Bill’s house. We bathed again once we got up to the Stevens cottage. The kids washed their clothes out each night so they could stand to put them on again the next day.

Each weekend I drove them all back to Cambridge, usually with a trunk full of booty: old fur coats, white flannel pants, wide ties and dresses from the forties, and the few books, leather-bound and lovely, that hadn’t been ruined. But we all ended up throwing a good deal of this away. Even after weeks of airing out, if it couldn’t be washed, it still stank.

It was, actually, a lot of fun. In the evenings we played board games or read, sometimes aloud—Sherlock Holmes, for instance. The kids were spirited and energetic. I think they had a sense of adventure about the whole crazy episode. In addition, they could see the results of their labor quickly and gratifyingly. By the third week we were able to start washing walls and windows.

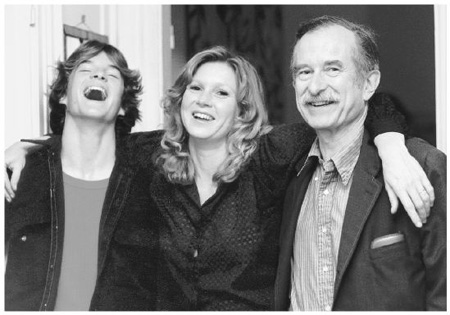

After they were done and had scattered to their various summer activities, I continued to come up each weekend, usually for three days, to work beside my father, scrubbing, patching the plaster, painting. Dad found someone willing to sand the floors—a miracle, given what was embedded in them—and he and I began the slow process of polyurethaning every floorboard in the house. I felt a real ease and companionship working alongside him. In the evenings, at the pristine-seeming Stevens cottage, we read or talked, and it was in these conversations that he expressed to me some of the regrets about how he’d lived his life. He also talked openly and freely, it seemed to me, about Mother, about her depressions and eccentricities, sometimes with regret, sometimes with amusement and delight. We discovered Garrison Keillor on the radio one night that summer, and routinely listened to him on Saturdays as we fixed our dinner and ate it. My father enjoyed especially his commentary on religion and on the Boy Scouts. He often laughed out loud as we moved around the kitchen.

He went to church on Sundays. I usually didn’t, preferring to keep working. But we often went to the Sunday-night hymn sings together and sat sharing a hymnal. By midsummer it was clear the house was salvageable; by late summer I was grateful for what working on it together had given to us, to me in particular.

Of course, even that summer there were signs I noticed, symptoms I wondered about. Often I spent the hours he was in church redoing something he’d said he’d finished. Once, for instance, he undertook to wash the upstairs bedroom doors. He was done in record time, but I saw, when I looked at them, that he’d actually only washed a few and even those not thoroughly—and thoroughly was what was required, in the circumstances. I scrubbed them all myself a second time.

And there was the issue of money and its connection to the work—which, after all, was hard and sometimes seemed endless. At one point that summer, a close friend in Randolph asked me why we didn’t hire someone to do more of it. “Surely your father has enough money for that.” But, of course, I didn’t know whether he did or not. I had no idea, actually, about his finances at this point. I’d seen them several years before, just after Mother died, but I thought buying Bill’s house might have taken him down to near zero again. In addition, I was keenly aware that I’d paid back only a small part of the money my parents had loaned me to buy my house—money, as I now knew, that represented all they had at the time. In a sense, I felt I owed my father my labor, especially if he couldn’t afford anyone else.

But there was a moment late in that summer when he took a call from one of my siblings who needed money to buy a house, just as I had once. I was on my hands and knees, scrubbing, when he answered the phone, but I could hear every word of Dad’s end of the conversation. It was completely audible to me when he readily agreed to a $12,000 loan.

I was stunned. If there was $12,000 to spare, my father’s friend was right—there was a kind of insanity to this tedious, never-ending work on our part. I remember, through that day and in the week following in Cambridge, thinking how strange it was, in a way, that my father could even have

allowed

me to do what I was doing if he had enough money to pay someone else to do it.

I certainly hadn’t wanted him to consider my labors a sacrifice—I’d worked willingly, lovingly—but the knowledge that he could easily have hired someone seemed to reveal a kind of callousness on his part about what those labors might have cost me—might be costing me. As I pondered it, I wondered if he was simply so used to my mother’s compulsive but absolute selfsacrifice on his behalf that he took my help for granted. Or was it a mark of some new failing on his part, a failing to see, to take in, the effort, the time it was all taking? He knew I was beginning now on my novel, he knew I had a grant, a precious one-year-only grant, that had let me escape from the round of teaching gigs all over Boston to write.

On the other hand, I told myself, what did it matter, really? I enjoyed the work, in fact. There was a part of me that saw this combination of elements in my life—four days focused writing in Cambridge, three days of hard labor in New Hampshire—as more or less ideal. And I was writing well, prodigiously well, when I wrote. If it cost me a little time, well, wasn’t that fair, considering his generosity to me in the past?

Still, that blankness about it, that lack of delicacy—the need to work on the house exposed this and made me aware of what seemed to me a lapse in him. Just as, in the next few years, the continuing work there exposed him more and more in his weaknesses, in his increasing inability to follow through with tasks, to think clearly about what needed to be done next and next and next, in his passivity about making decisions.

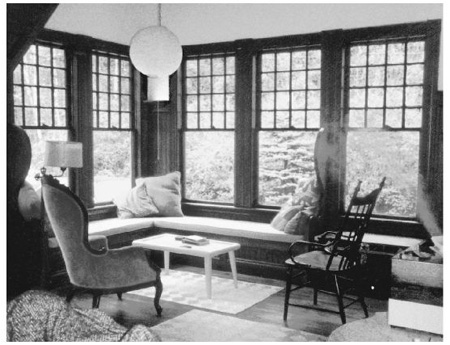

Even so, even so, I’d do it all again. The house came around, finally. It was livable; then, in another year, enjoyable. And diminished as he was by that time, my father did enjoy it. As I enjoyed his enjoyment. I liked watching him sit in the sunny corner of the living room by the window seat in the late afternoon, listening to Mozart, looking at the birds flying in and out of the blue spruces and the lilac hedge. I liked sitting with him on the front porch in the morning sun with a cup of coffee, talking or listening to the river rush by below us.

And even after he was diagnosed, even after we all finally knew what his failings had been about, the house was a kind of refuge for him. While he was living in Denver, he came east each summer, and I usually spent a month or so up there with him, and each of my brothers were there a week or more. My times were, as usual, quiet. We took walks, we read, we went to church. I continued to work on the house too, but he’d pretty much stopped being able to. We talked. His concerns by now were more tightly circumscribed, focusing on my sister and her children, on the house itself, on me and my life—and he was a bit perseverative about them all: we covered the same ground many times over.

The last of these summers before he came east to live permanently at Sutton Hill, he brought a box of personal papers to New Hampshire with him. Sitting in his bedroom facing the mountains, he spent some time each day going through them one by one, then tearing them carefully into pieces and throwing them away. I recognized the handwriting as I carried his wastebasket down to the trash: they were my mother’s letters to him and his to her.

I used this behavior later in a novel. I had a middle-aged man’s dying mother destroying her correspondence with her husband. I had the son emptying the trash regularly, as I did, and looking at the fragments of his parents’ past—his own history, in a sense—as he bagged them up and threw them away.

My character’s situation was different from mine, though. His parents had divorced years earlier, and he yearned to know his now-dead father. He was, in a way, angry that these letters were being taken from him, that he had to collaborate in disposing of them. He felt an intense desire to read what passed through his hands.

I felt some curiosity, of course. I felt too that I held a history, a story, as I lifted the basket and upended it into the mouth of the plastic bag each time. I won’t say I was without regret as I hauled the trash out for collection each week.

But I knew my parents—knew enough of them, anyway— so that what I was most aware of was a kind of awe for my father as he carried out this task. Every time I passed his open door (it reminded me of that open study door of my childhood, actually) and saw him there, reading and then carefully tearing the letters in two, then in four, what I felt was a deep and compassionate admiration and also a kind of amazement at his consistency in this one task. That he, who had so much trouble completing almost any other chore, should be so thorough and undeviating in his daily work at this prolonged and permanent farewell to his own life, his past, his love, moved me more than I can say.

Chapter Eight

FROM THE TIME my father arrived back east permanently to live near me in a continuing care retirement community in suburban Boston, he was hallucinatory. This had been only an occasional problem in Denver, so it seems clear that it was in part the difficult transition that triggered it—the transition to a new, comparatively tiny space (he’d had a two-bedroom apartment in Denver with a view to the mountains; here he had one room with a lavatory), to the loss of his books (there was space in his room for only one standing bookcase full, down from a dozen or so in Denver), to the sudden absence of my sister and her children, who’d been part of his everyday life there.

In retrospect, were I to choose a place for him again, knowing what I know now, I’d choose proximity over programs, over elegance, even over reputation. Because what was hard for me at Sutton Hill was to drop in on Dad for a lot of short visits or to have him over for a quick casual meal—and that’s what would have been best for both of us. But it took forty minutes just to get to Dad. And it was harder still to have him visit at my house. To drive out and get him, come back, return him at the end of a visit, and drive home meant three hours in the car. Most weeks I saw him only once or twice.

He was, then, really institutionalized, and it was damaging to him. The progression of his disease from this point on was more rapid than it had been before. He changed, and changed again. And in response, often lagging a step or two behind him, I changed also. Slowly, reluctantly, I learned new ways to behave, and I too was transformed, at least with him, as his illness deepened.

My father never really understood where he was at Sutton Hill. He had to be reminded why he was there over and over, and then he’d forget again. When he first arrived, he could still give a kind of lip service to the explanation he’d understood earlier: he had Alzheimer’s disease. Often now, though, saying this seemed a kind of mindless habit, something he’d taught himself to repeat without fully comprehending it. If I specifically reminded him that he was at Sutton Hill because they could care for him through the course of the disease, he’d politely concur. But my reminding him of that was usually and increasingly provoked by his having asked when he was going “home” or how long he was staying “in this place.”

My original impulses hadn’t been to try to support my father’s delusional life. I’d been fooled by my first few experiences with his hallucinations, when I’d been able to talk him out of them, to reason him back to reality. I’d persuaded him that they were the result of fatigue, or of pushing himself too far, or—once we knew he had it—of the disease itself. And at this early stage, when I explained this to him, when I corrected him, he’d been able to step away from his visions, and from himself as their creator, and comment on the oddity of it all. I think I felt a kind of pride in this. I misunderstood it, in my vanity, as a gift I had with Dad.

So for a while after his arrival at Sutton Hill I would try to argue him out of his own perceptions. “No, Dad, look, when you get close you can see that this is just a reflection, not someone out there watching you.” “No, Dad, that’s just a dog barking, way off in the distance, hear it? It’s just a dog, not a person calling.”

Slowly, though, he became unable to accept my version of things. Slowly it became clear to me that my gift was gone. And simultaneously I understood that this was because it had never been mine in the first place, but his—the gift of enough remaining undamaged brain to recognize the damaged part for what it was when I pointed it out. He had lost that now. It dawned on me that my insistence that what he saw wasn’t “real,” that what he heard was not what he thought it was, was making an insurmountable barrier between us, so I stopped.

Now when he spoke of animals in the building or visits from my mother, I would commiserate or be pleased for him. And most of the time I managed to feel these things—the appropriate sadness or pleasure to accompany the delusion. I thought of him as

having had

the experiences he reported. I thought of them as being part of his reality, a part I needed to accommodate and accept. And in the end I did, so thoroughly that it began to strike me as odd when others didn’t or couldn’t. The nursing staff, for instance, was completely unable to make this leap. When Dad spoke delusionally to them in my presence, they were openly dismissive. They reported his “mistakes” to me with contempt. This bothered me, more than a little. Had they had no training in the way these events seemed to occur to a delusional Alzheimer’s patient? I wondered. Could they not flex their imagination a little bit? Their compassion?

Sometimes the hallucinations seemed painful. One of his recurring ideas, for instance, came because he missed his library, all those books he’d left behind in Denver. Within a few months of his arrival at Sutton Hill, he became convinced someone had stolen them from him, that they were locked somewhere in the basement of the building. He often asked me to come with him to find them.

Tentatively I’d say I didn’t

think

they were here and offer my understanding that he and my sister had sorted through and gotten rid of most of them. But this cut no ice with him, so we’d walk around the halls of Sutton Hill looking for the passageway he was certain he’d seen, the one that would take us to the chamber where the books were kept—until we would arrive, to my father’s deep confusion, at the activities room or the lounge or someone’s office or the country store. A dead end, the remembered doorway now a plastered-up wall, as in some Hitchcock film. (He wandered when I wasn’t there too, which bothered the staff, but I decided not to tell them that he was just looking for his books. I knew they’d insist to him that there was no basement and there were no books, and then he’d conclude they were “in on it”—the theft, the plot.) Sometimes he’d worry about family members, or about other residents, about bad things having happened to them.

Most often though, the hallucinations I had to accept as part of his reality were pleasant ones. I’ve mentioned earlier that my mother came to see him, as did his parents. He reported lively visits from friends. And gradually there came to be a focus to his dementia. The patterns and rhythms that had governed my scholarly father’s life asserted themselves here too—from

within

this time—to shape his understanding of his new circumstances: Sutton Hill became some kind of university, a university in which my father’s role was multifarious and changeable. Increasingly, when I’d ask him what he’d been doing, what was new, he’d answer that he’d been preparing a lecture. Or that he’d

been

to a lecture (and he did, in fact, go to some in this well-organized community—on transcendentalism, on art history— which probably reinforced the nature of his fantasies). Often he had the sense we get in dreams of being terribly late for something, or terribly unprepared, but more and more of the time now there was one specific context for this—a scholarly context. One time he told me he was supposed to lecture on

Hamlet.

He shook his head. Of course, he knew

Hamlet,

but really, to give a lecture . . . He didn’t know if he could do it. It was going to be a real chore to prepare.

He always had a lot of reading to do now to get ready for one thing or another—though in reality, of course, he couldn’t read at all any longer—and when I visited he always reported how busy he’d been. Sometimes it seemed he was the professor; sometimes more a student, doing papers, going to class. He wondered, once, when he would get a new room assignment, and I thought he must see Sutton Hill as a college, or perhaps even a kind of prep school.

One of the therapists, a woman who looked a lot like my mother, actually, and whom my father liked, spoke to me of her concern for him. He didn’t come to their exercise classes or their musical afternoons or their crafts events. When she passed his room, she always saw him alone, just sitting blankly in his chair or dozing.

I defended his behavior. I said he’d never liked crafts, that he’d never cared for swing music or Glenn Miller—that he didn’t even know who Glenn Miller was. (I didn’t tell her he’d charmed my mother early on by his unworldliness in pronouncing

boogie-woogie

with soft

g

’s—a detail I once used fictionally.) I said he’d always been relatively solitary. I told her I didn’t think she needed to worry about him, because his delusional life was unusually full and satisfying.

I told her I thought he was happy. I still think, at that time, that he was. But perhaps I shouldn’t have taken such comfort in what seemed the chance kindness of my dad’s illness at this stage. Perhaps I should have wished for him that he embrace enthusiastically the activities offered him, the reality of his situation. That he

go

to exercise classes, that he

learn

to weave or dance. Maybe if he had done those things he would have lasted longer, made more friendships of a sort, and stayed more firmly in touch with all of us too.

But I didn’t. I welcomed the sense of usefulness and purpose his delusions gave him. I was glad when he reported he’d done things—familiar Dad-like things—that I knew he hadn’t done. I lied. I went along with his mistakes. I still don’t know if this was right or wrong, but I would do it again. I would choose to have my father feel happy and competent in some parallel universe, rather than have him build something from popsicle sticks or learn line dancing or reminisce publicly—he who almost never spoke of himself or of his past.

I let him go into his delusion and didn’t push him at all into his life at Sutton Hill. I was pleased for him that he’d come home to his own self-invented university.

One afternoon, toward the end of one of my visits, my father said, “You know, one thing I haven’t figured out about this place.”

“What’s that?” I asked.

He looked puzzled. “Well, no one ever seems to

graduate

from here.”

I burst into laughter, so he laughed too, purely at my amusement. He had a wonderful laugh. Not the sound of it so much but its innocence, the way it seemed almost to take him by surprise, nearly to embarrass him.

That night, when I told my husband what Dad had said, he laughed too.

Encouraged, I elaborated on it. I made macabre jokes for my husband in a sardonic W. C. Fields voice: “Well, Dad, it depends on exactly what you mean by

. . . graduation.

” “Well, in a certain sense they all do, Dad, they

all

do.”

I laughed, and my husband laughed, and I know if my father had been there—my father as he was before he was ill— he would have too. He would have given himself over, with that surprised, almost startled delight, to the joke he’d made of his illness and laughed right along with us.

If Dad’s delusional life had continued in this benign way, it would have been easy for me to continue to accede to it. But as the Alzheimer’s disease was progressive, so was the nature of the delusions. Gradually there arose other, stickier dilemmas, ones I had no ready response to, instinctive or otherwise.

He was agitated when I arrived one morning. I asked him what was wrong. There’d been a fire, he told me. A bad one. The residents had all fled the building in their pajamas. (Later I would find out there was, indeed, a fire

drill

in the night, required occasionally by law, and, yes, the residents had gone outside and milled around on the lawn in their pajamas until the all-clear was given.)

“How awful,” I said.

“Worse than that,” he said, “there were little children killed.” He was nearly trembling, he was so upset.

I looked away. What was I to say now? Could I pretend a grief I didn’t have? Could I

act

as upset as he was? “Are you sure, Dad?” I finally asked.

“Of course I’m sure. I was there.”

I began to back away from this one. “You know, I don’t

smell

smoke. If there’d been a fire, surely there’d be some sign of it, surely we could—”

He shook his head, cutting me off. “Little children,” he said. “Dead.” He watched me steadily, waiting for me to recoil, for my eyes to fill with tears, for me to share his pain.

I couldn’t. I wouldn’t. I felt it would be wrong.

Yet I’d acted as though I believed countless others of his delusions, his hallucinations, hadn’t I? What line was I drawing here?

He waited.

I felt accused. “You know, Dad,” I said, “maybe it was a kind of nightmare you had. Sometimes they can seem so real—”

“It was no nightmare.” His lips pressed together. “There were children who died. And everyone around here acts as if they were just . . . puppies or something.”

I tried deflecting the central point. “Well, I’m sure the staff is upset too, Dad. But they have to go on running this place. Maybe they can’t allow themselves to feel it as much as you do. Maybe they’re saving their mourning for later.”

“They are not,” he said sharply. And he looked at me with a gaze as cold and critical as he’d ever directed at me. Clearly he believed I was as inhumane, as inhuman, as they. And worse, that I was an apologist for them, for their attitude.