The Story of My Father (9 page)

The visual pathways in his brain began to fail. The first thing to go had been his ability to read, to connect those symbols on the page with a meaning—though he could still pick out words separately, evidence that the problem was not purely with his eyesight. Still, it was his eyesight he blamed, and it was with his eyesight that he wanted help. He had had cataracts removed while he was in Denver, and in fact one cornea had by now clouded a little again, so I took him to the eye doctor for that; we drove to the hospital in Concord one day and I watched as Dad sat forward in the darkened room, his chin resting on a stabilizer, and the laser quickly, magically, cleared that eye again.

But it didn’t give him back what he had imagined it would—his ability to read and, beyond that, probably, some old sense of himself. He went on asking me, each time I visited, to take him for another appointment to the eye doctor, to get him a new prescription, a new pair of glasses, and I continued to put him off. As time went by he grew irritated at my slowness to respond to his need, at my indifference, as he must have seen it, to his dilemma.

And so finally, unable to bear that, I scheduled another appointment. I asked the doctor ahead of time to try to help my father understand that new glasses wouldn’t help. And because he was a doctor, because he was a man, my father listened to him, and for a few days remembered:

There was something

organically wrong, but it wasn’t with his eyes, it was with the messages between his eyes and his brain.

And then he forgot and began to agitate again for another doctor’s appointment.

Increasingly now, too, he misunderstood—“misread”—the visual. Oliver Sacks has written about our way of seeing as being learned; and scientists have begun to understand that, if certain visual synapses—electrical connections between nerve cells in the various visual systems of the brain—aren’t formed and “exercised,” built up, by a certain age, they can’t be developed later. Sacks speaks of a blind patient whose sight was given to him surgically in middle age who never learned “how” to see certain things.

And now I watched my father as those synapses stopped working in his brain, as he “unlearned” seeing. Shadows became for him not the absence of light but dark

objects,

as perhaps they appear to infants and little children. Their presence was inexplicable and disturbing to him. His own shadow underfoot on a sunny day, for instance, was often an irritant, a strange black animal dogging him. He would sometimes kick or swat at it as we walked along.

In the later stages of his illness, he stopped “seeing” food on the left side of his plate. At first everyone worried about his appetite, because he was growing so thin anyway. But then an attendant noticed the pattern. He was pleased and excited to report to me that if he simply rotated Dad’s plate a half circle, he’d soldier on and clear off the whole thing.

Some “hallucinations” may have been simply mistakes. I thought for a while that his seeing a bull in the yard outside his window was hallucinatory until I noticed in the Victorian iron bench out there two curving back pieces like horns and, below those, a pair of floral motifs that looked like eyes. Just a misreading of what was there, then, not purely an invention.

Sometimes it wasn’t clear what was going on. One day, as we were leaving his room, he gestured at his bathrobe, hanging from a hook. “Dave Swift,” he said, and laughed. “He’s been standing there all day.” And I looked at the bathrobe, hung there like a tall, skinny man in plaid, skinnier than my Uncle Dave but not by all that much, and I laughed too. But thinking about it later, I couldn’t figure out whether this was a mistake or a joke, a misreading or a hallucination. Who could say what was going on in what part of the brain?

And what were the impediments he saw late in his illness that caused him to tiptoe so carefully over something I couldn’t see, or to get down on the floor and crawl around it? Simple disturbances in his visual pathways, in the way he saw something

real?

or internally elicited disturbances that led him to invent something where there was nothing—to hallucinate?

Of course, he had delusions too. When we were visiting one day, he told my husband that there was an underground railroad at Sutton Hill. My husband laughed, thinking that Dad was making a joke about his wish to escape. But later in the day Dad soberly pointed out to him the spot where the train pulled in. And Marlene reported to me that she found him at this spot more than once, that he told her he was waiting for the train.

Oddly, this seems not unconnected to the intention of the design of Sutton Hill. The shops and the bank, post office, and grocery store were all arrayed along what was called Main Street, an indoor walkway with an old-fashioned clock tower at one end. All had whimsical storefronts. Why not give Main Street a railroad station in your imagination too?

Sometimes the delusions were painful, like the one about my sister being abducted by terrorists. I tried to reassure him that time; I reported that I’d spoken to her and she was safe in Denver. But he couldn’t be comforted. He persisted. He found me, I think, hard-hearted in the face of his certainty that she was in mortal danger. Finally I called my sister to ask her to get in touch with him herself and tell him she was all right.

Sometimes the delusions were pleasant. He told me about wild, elaborate gatherings with other residents. They were putting on a play together. They’d had a kind of combined lawn and pajama party. Sometimes he would have heard an old friend, often someone long dead, lecture or preach. Sometimes he’d see Mother. I came to feel that these were the residue of dreams, dreams that seemed no less real to him than the fractured reality he had to live through each day and so, in his interpretation, became a part of that reality.

Not all Alzheimer’s patients have hallucinations and delusions; the estimates vary wildly in the literature from 30 to 60 or 70 percent. For those who don’t, the course of the disease is simply progressive cognitive deterioration. But when they are present, they too are traceable to conditions in quite specific parts of the brain and probably also to failures within networks linking certain areas.

Hallucinations and delusions in AD patients are born in the same areas of the brain in which schizophrenics are also disturbed —primarily those areas responsible for receiving visual and auditory signals. But the nature of the Alzheimer’s hallucinations and delusions is generally different from those of the schizophrenic. More often, schizophrenics see themselves at the center of the delusion.

They

are being persecuted,

they

are being abducted by terrorists or monitored by the CIA. In any case, they are the main actors in the drama. The Alzheimer’s patient is more likely to stand to the side, as Dad did at this stage of his delusions. More likely to report that others around him are doing bizarre things or that someone else is in trouble or danger. More often he has been just a witness, as we so often are in dream life, to the strange misadventures and tragedies around him.

And oddly, though the presence of hallucinations and delusions is correlated with a more rapidly advancing version of Alzheimer’s and some researchers are inclined therefore to see it as a subset of AD, most experts believe that there is

less

cortical damage,

less

ventricular enlargement, in the hallucinating or delusional patient at this stage of the disease. It is as though the patient

needs

more cortex to develop and elaborate the hallucinatory or delusional ideas.

I knew neither of those facts at the time. I’m grateful, of course, not to have known the first, that these symptoms are associated with a quicker arrival at what is euphemistically called the “cognitive end point” of the disease. But if I’d known the second fact—that these symptoms may indicate more cortex—I’m sure I would have taken pride in it.

Why is he so crazy?

Ha! Because he’s got more brain left.

This is how we are, after all, watching the people we love disappear. This is what is left to us; this is the comfort we can take. “He was never violent.” “She always loved being with the children.” “She’s just as stubborn as ever.” I took pride in my father’s always recognizing me, as I was proud that he retained his graciousness, that he always said to Marlene—and, later, his other caretaker, Nancy—“It was grand to see you” when he’d run into them in the hallways. I was even proud when he had an elaborate delusion about the Civil War near the end of his life and mistook my foot for Antietam.

Who but Dad?

I thought.

Who but Dad?

Whatever the remotely personal characteristic that seems to have escaped the disease, we seize on it. Whatever idiosyncratic neuronal patterns still fire, still express something laid down with care and attention and love years earlier—this is important, and we cling to it.

He’s not just an Alzheimer’s victim. He’s

still, somehow, himself. He’s managed to hold on, to outwit this disease, in this one or two or three ways.

But of course, I knew better. Outwitting the disease isn’t possible. It wasn’t owing to his character or depth of attachment to people that Dad remembered us. It was what the disease spared while it destroyed something else. He could have stopped recognizing us earlier and forgone the delusions. He could have dropped verbs—there is a part of the brain specific to verbs—and been stuck with a list of nouns to repeat without much skill at connecting them by actions. It was the

disease

that determined what would go first and what would be left, not vice versa.

I remember talking about him with an old friend of mine, someone who’d known Dad too, years before. By then, near his death, Dad was occasionally violent, and I recounted that to this friend.

He shook his head. “Isn’t it strange,” he said, “that under that gentle, sweet exterior there should be all that violence?”

A different model, this one: Freudian. One that saw the constraint of the superego eaten away by the disease, and the elemental core, the uncontrolled center, the id, as still remaining, unbuffered. The violent Dad who was secretly always there, emerging now that he’d lost control of himself.

No, I said. No, that’s not the way it worked. It was his

brain,

not a theoretical construct in his

mind,

that was being destroyed. He was

organically

a different person. I was trying to be pleasant and conversational, but I remember feeling a real anger, even a contempt, for my friend in his misunderstanding.

Yet I indulged myself—didn’t I?—in the correlate belief: that the good stuff he retained, he retained because of who he was: because of the fineness, the excellence, of who he was. And that was just as much a superstition, a fiction, but one I didn’t wish to shake. And I didn’t ask myself to shake it, though I did know it was a fiction. “He never didn’t know me,” I said proudly. “Up to the end, he knew me.”

Technically, importantly, this was true. But there were several times when his gaze at me went blank, momentarily, though he’d known who I was seconds before. And one of the times he was violent with me, when I was struggling physically with him to bring him inside after a walk and he didn’t want to come—the last outside walk we took—he looked at me with hatred and contempt and I think he didn’t know me at all. I hope not, actually. I hope he did think I was someone else.

But even the last time I visited him when he was conscious, he recognized me at first.

When I came into his room, he was standing by his crib bed, gripping its rails with white-knuckled intensity and staring fixedly at something he was seeing on his blanket. He was slightly bent at this point, a gentle Parkinsonian curve to his back. I spoke to him, but he didn’t seem to hear me. I went over and touched him, I swung my head just under his face and looked up at him, smiling.

“Hi, Dad,” I said.

He started. “Why, Susie!” he said, calling me by my little-girl name. And it seemed that he was actually

seeing

me as a little girl in that moment, his smile was so delighted, his voice so light and glad.

He knew me. I clung to that, to those happy moments at the start of each visit—before I denied what he knew to be true. Before I failed to respond humanely to what he reported as calamity. Before I told him what I could not or would not do for him today—take him to the doctor, find his books, get his car back. Before he said, as he did at least every other time I got up to leave, “Say . . . are you driving? I was wondering if, maybe, you could give me a lift home.”

Chapter Six

LISTEN SOMETIME to the way people speak of others’ deaths, of their dying. It’s full of judgment—censure here, praise there. What we all approve of, what we like in a death, is the dignified old person, still relatively intact physically and all there mentally, who carefully puts his clothes away one night, goes to bed, and never wakes up. We like someone who doesn’t suffer terribly and make us watch that suffering. Who

has all his

marbles

till the day he goes, who

just doesn’t get up one day.

“That’s the way to do it,” we say, as though praising a canny decision.

Susan Sontag, in

Illness as Metaphor,

writes about the phenomenon of blaming people for their illnesses:

With the modern diseases (once TB, now cancer), the romantic idea that the disease expresses the character is invariably extended to assert that the character causes the disease—because it has not expressed itself. Passion moves inward, striking and blighting the deepest cellular recesses. . . . Such preposterous and dangerous views manage to put the onus of the disease on the patient.

I felt this kind of judgment on Dad in his fellow residents at Sutton Hill. He always lived among the general population there (no such thing as an Alzheimer’s ward yet, just that short time ago!) and I could sense their recoiling from him. Annie, one of his nurses, funny and loving but indiscreet to the core, confirmed it for me—the irritation and contempt his neighbors felt for him. “Those old ladies,” she said, shaking her head, full of her own judgment. “They act like you get to

choose

the way you go.”

I was sorry Annie told me this, but I wasn’t surprised. The fact was, of course, that I recognized my own judgments in theirs. I even recognized Dad’s judgments. I remembered he’d said, years earlier, of the wife of an old acquaintance who had Alzheimer’s disease, “I hear she’s completely ga-ga now.” The tone was mocking, not kind—surely the same kind of thing, in the same kind of voice, that his neighbors said about him now. That I had said about wacky old people, too, and felt about them. Until my own father turned wacky.

I think, until I lived through my father’s dying, that I thought death finished a person’s story, that it was part of the narrative arc of someone’s life and made a kind of final sense of it. The deaths I’d known until then—and there hadn’t been many, my family was so long-lived—had misled me in this regard. I thought you

earned

a certain kind of death. That my grandparents were still alive and wholly themselves because of

who they were

somehow; because of how they’d lived. And my mother! Well, hadn’t she had the very death she would have wished? In an evening dress, at a party, drinking, smoking, after a day of pleasure and deep, satisfying excitement?

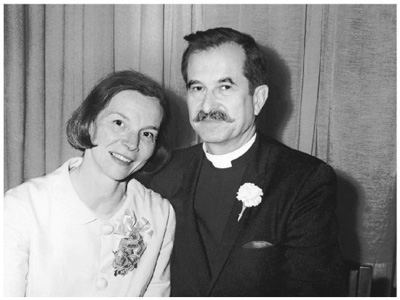

In 1979, my mother was sixty years old, two years older than I am as I write this. She was full of intellectual curiosity, full of energy and life, full of ego and emotion, full of herself. My father had a sabbatical that year, starting in the fall, which coincided with his retirement as academic dean from Princeton Theological Seminary, where he’d gone when he left the University of Chicago—from now on he would just teach church history. My parents decided they’d rent their house out and come to live in Cambridge, near me, for that semester.

I had mixed feelings about this, feelings that centered, of course, on her. Would she drop by constantly? Would she want to see me all the time? More accurately,

Would she eat me alive?

I was especially worried because 1979 marked a time of change for me in my writing life, and I was afraid her needs would somehow interrupt that life.

I had begun, only a year or so before, to send stories out, first to magazines that might pay me something, then to little literary magazines. Nothing had been accepted, but I’d had what writers call “good” rejection letters, personally written ones; and I had an odd kind of confidence in myself, an assumption that it would happen—my work getting taken for publication—and it would happen soon. I’d begun to meet other writers through a few classes I’d taken, and then among the parents in the day-care center where I worked. The winter before, I’d applied to graduate writing programs—not so much for the sake of the course work as because I thought I might get a fellowship that would let me stop working and write more or less full time for a while.

I did get a fellowship—several fellowships, actually. I could choose where I wanted to go. The biggest dollar amount, though, was from Boston University’s Creative Writing program, the program that would also be the least disruptive to my life. I could stay home. More important, Ben could stay home. There would be no complicated moves and adjustments to make. I accepted BU’s offer and was looking forward to living and working in a community of writers for a year. What I feared was that my parents’ arrival might threaten that in some way. Nonetheless, I found them a big lovely house to rent about five blocks away from mine.

On the evening they arrived down from their summerhouse in New Hampshire, they came first to me. Mother was tearful and tired, overwhelmed—unreasonably, it seemed to me—by the thought of the cat they were going to have to care for: it came with the house, and she foresaw difficulties because of their old dog, who came with

them.

Already! I thought, irritated with her.

I drove up with them to show them the rental. We entered through the back door, into the big kitchen. There, on the table, was a note from the friend of the owner who was in charge of the house while the owner was gone.

Groans from Mother: Oh, God, what on

earth

was this about? She started to read it out loud to us.

The friend welcomed us. She told us where things were, who to contact in case of various kinds of emergencies, how to reach her. Then she said that she was sorry to have to tell us that, tragically, the cat had recently died.

Mother whooped with mean joy and literally danced around the kitchen. Dad and I couldn’t help laughing with her. By the time I left she’d poured herself a stiff drink and was happily taking in the big open rooms they would live in for four months.

Nothing happened that fall as I’d feared it could. It was as though the convenient and welcome death of the cat were a kind of perverse blessing. My mother, who had begun to write poetry again after years away from it, enrolled in a class at the Radcliffe Seminars and was almost as busy as I was. My father went daily to the Divinity School Library at Harvard. I saw them only two or three times a week, sometimes for a meal, sometimes for a shorter visit. They poked around Boston and Cambridge together, and I think Mother felt, in a way, returned to her youth; her father had had a church in Belmont when she was an adolescent. They took care of Ben, who was then eleven, on the day he had no school in the afternoon, which was one of my longest days on campus at BU. It was an easy, lovely time for us all. I remember that my father came over one day and helped me plant a dogwood in my front yard. They both came over for Thanksgiving—Ben was with his father—and between courses, my father and I raked and bagged the fallen maple leaves in my tiny backyard while Mother sat wrapped up on the deck in the slanted gold afternoon sun, drinking wine and crying out from time to time about how

divine

this was.

I gathered, though, that my father’s work wasn’t going very well. My mother confided to me that being a dean for fifteen years had “absolutely

ruined

your father as a scholar.” I wasn’t sure how to take this—whether it was just part of the usual drama she always tended toward, or of the jealousy she’d always felt about the extra demands being dean put on my father and about the freedom the president of the seminary had felt to call on Dad at virtually any time.

But he complained, too, of not getting much done. He had a grant during this sabbatical to work on a revision of his biggest text,

The History of Christianity,

1650–1950,

and he clearly felt his usual strong sense of obligation to accomplish a lot on that account. But he also saw the text as embarrassingly hostile to Catholicism, something that seemed particularly egregious in these post–Ecumenical Council years. He wanted very much to change it, because the world of the church itself had changed and he along with it. It was odd, then, and probably more distressing to him than he said, that he was off his stride somehow with his scholarly work.

My mother, on the other hand, was working very hard at her poetry and was unusually happy—except for her own beloved mother’s sudden illness, a stroke, which had kept my mother driving frequently to New Haven from mid-fall on to see her. By Thanksgiving, though, it seemed clear my grandmother would survive and recover completely, and my mother was ready to turn to her end-of-the-semester paper on Elizabeth Bishop with enthusiasm.

The ten days or so after our Thanksgiving meal together were busy for me too. I had several term papers and also some fiction to write. My son went off to stay at his father’s house for a week, and I holed up with my typewriter and a lot of take-out food and didn’t see my parents until December eighth, the day after I turned my last paper in.

That morning was unusually warm and sunny for December. I picked my mother up at about ten and we went Christmas shopping together, hitting one funky Cambridge store after another. She loved the shops, so different from those in Princeton. She was cheerful and exuberant. At Mobilia they were serving mulled wine. “Why, certainly!” my mother said, and she had two glasses full as we looked at things.

Later in the day, she called me to tell me that my younger brother’s first child, a boy to be named Michael, had just been born by cesarean section. I stood in the kitchen, listening to the italics in her voice. She sounded high, exultant. Oh! she had to rush off now, she said. She and Dad were going out to tea in Belmont at my great-aunt’s house. Later I found out that Mother got into an intense political argument there—she enjoyed nothing more. That evening, I knew, they were to go to a dinner party in Cambridge.

I was alone that night, finally with time to work on Christmas presents. When I’d finished sewing a few things, I took advantage of my son’s absence to go to bed early and read. I had turned the light out, but wasn’t asleep, when the phone rang around midnight. It was my father. He apologized for waking me. My mother, he said, had collapsed at dinner and been taken to the hospital with an apparent heart attack.

“

And?

” I said. “How is she?”

He cleared his throat. “She’s gone.”

I cried out, “No!” (My tenant, a dear friend through all these years, says she remembers that night, remembers the wild cry she heard through the walls and only later learned the cause of.) After a moment, I was able to ask a few questions. And then suddenly it seemed crazy to be talking on the phone. Here we were, only a few blocks apart. I had to be with my father. I had to go. I got dressed and drove up Avon Hill, and we sat in the rented kitchen, dry-eyed and stunned, until around four-thirty or five in the morning, both of us—as we said again and again—fully expecting my mother to waltz in at any moment and begin

pronouncing

on one thing or another.

I think this feeling was compounded for him because he hadn’t seen her again after her collapse at the party. She’d been wearing her evening dress, talking and drinking, and then suddenly she sat down, yawned once or twice, and slumped over, unconscious. When the ambulance came, the EMT guys asked my father about her medications. He wasn’t sure of all of them, so he drove home to gather them up instead of going in the ambulance with Mother.

By the time he got back to the hospital with her collection of pill bottles, she was dead, though he didn’t know it right away. He sat in the waiting room as they continued to work on her for a while. When they came to tell him their news, he asked to see her, but they discouraged him; they told him what they’d done to try to save her had been invasive and might be difficult for him to confront. He acceded to them, as was his nature. (And indeed, when we picked up her rings and clothing a few days later, there was blood—Mother’s dried brown blood—on everything.)

But I think now that not seeing her dying, or dead, made it hard for him to accept completely what had happened. That, and her dramatic and bottomless vitality. One moment she was herself, theatrical and full of vivid life; then she was gone from the stage, disappeared forever. No wonder in his delusional life a few years later she was often there, alive and busy with one thing or another.

Over the next few days we planned a service and made the arrangements. My siblings and their families assembled slowly, my poor younger brother leaving his wife and day-old son in a hospital in Colorado to come east and mourn his mother. The rented house was noisy, full of the exuberance of the young kids, almost all boys.

The doorbell rang one morning in the midst of this. I answered it. It was the director of the funeral home who’d arranged for Mother’s cremation. He’d come to drop off her ashes. I took the box. It was glossy cardboard, square and white, like the boxes that held the corsages boys gave you in high school. I remember standing with it in the wide front hall after I’d closed the door, listening to the happy shrieks of my nephews and my son playing wildly, unsure what to do. My father was upstairs in his room with the door shut, which seemed to be the way he was managing his grief. I didn’t know whether it would be an intrusion to knock on the door and give him the box. I couldn’t even decide on an appropriate place to set the box down if I didn’t take it upstairs. I don’t remember, actually, what I did do with it—but I remember feeling overwhelmed, suddenly, one of many moments through those days when I felt as though the simplest choices were beyond me.